About a hundred and fifty years ago, the National Theatre booked the courtyard of the famous “Clock House” of Madhusudan Sanyal in Chitpur, for a sum of Rs 40 per month. Tickets were sold for a performance of the play Nil Darpan (written by Dinabandhu Mitra), which was to be staged on the 6th of December, 1872 making it the first commercially performed theatre in the history of Indian art. This event went on to have a profound impact on the social and cultural evolution of Bengal for the next hundred years.

The rustic Jatra(moving plays), duets between poets and ballads waned out from the scene. The newly Europeanised young Bengalis, began to look at the old customs followed so far, as uninteresting. As a result, many of these English educated young men began to feel the need for European-styled entertainment, which was fuelled strongly by the Hindu college pass outs. Prior to this, for about eighty years, since the attempt of Russian Lebedev to construct Bengali theatre, the affluent and privileged class of Bengalis did not leave any stone unturned in trying to establish Bengali theatre. But these initiatives were mostly an outcome of the personal interests of the wealthy class, that was often inevitably dropped due to the death of such a donor, or due to the loss of interest from their side. These causes often prevented the growth and long-lived attempts at theatre building. Besides, most of these productions were never open for the masses to attend, rather they were restricted to an only invite group, most of which comprised invited British personnel or elite Bengalis.

The hosts of those theatre productions shared the common interest of entertaining the British high command- many of whom resided in Bengal- to gain some privileges from them in return. Establishing theatres came to be considered as a status symbol for the Babus of Kolkata. Legend has it that, Raja Pratap Chandra Singh from Paikapara, along with his younger brother Iswar Chandra Singh jointly established Belgachia Theatre, which went on to produce a play named “Ratnabali” with a production value of ten thousand rupees in the year of 1958! For the sake of British people, they translated the play into English with the effort from Madhusudan Dutta. Upon witnessing the production of Ratnabali, Michel Madhusudan found inspiration in playwriting, and as audiences, we were privileged to find the play Sharmistha as an outcome.

From the mid of the 19th century, the emergence of one theatre after another, and the beginning of such a culture, and its disappearance within a few days, was the beginning of a trend that sparked the interest of kings, zamindars and ordinary folk. It was during this period that a group of young minds from the Baghbazar area of Calcutta, aired the idea of theatre acting, which in turn resulted in the establishment of the Baghbazar Amateur Theatre group. Later this name was changed to Shyambazar Natyasamaj. Some of the notable names from this youthful group were Nagendranath Bandopadhyay, Girish Chandra Ghosh, Radhamadhav Kar and Ardhendu Sekhar Mustafi. The commercial theatre of India was born through these hands.

The success of Leelabati sprouted the idea of selling ticket in Nagendranath’s mind that could help ordinary people to attend the show in an appropriate way. The show was so successful that many viewers had to be in fact turned away. Years ago Radhamadhav Halder and Yogindranath Chattopadhyay tried opening The Calcutta Public Theatre for the masses, but this was an unsuccessful attempt.

It might be noted here that none of the youths from the Shyambazar theatre group had ever thought of making a career out of selling tickets and acting in the theatre. The idea of selling tickets was with a separate plan in mind. In those days almost everything from a mirror to the comb required for the play had to be bought by those who were in charge of the play. This was because the idea of renting out theatre props hadn’t yet started. This production cost had to be raised by requesting money from everyone. This resulted in people being annoyed too. While there was no question of paying off the actors for their performances, the sale of tickets at least aimed at paying off production costs that could now be funded while also enabling those who wanted to buy tickets to enjoy the show. This would also put an end to the bizarre and annoying situation of lending money from well-wishers.

Scarcity of money led to the inevitable choice of Dinabandhu Mitra’s Sadhabar Ekadasi which could be staged with much less production expenses. In the fourth production of this play, the author Dinabandhu himself was present in the audience. For their next attempt, they chose Leelabati, a play by the same playwright and raised enough production funds by asking for financial help by visiting people door to door. Luckily for the group, the word-of-mouth praises of this production had reached such a level that the number of audiences exceeded the limited seats of the theatre, as a result of which many had to be turned back. But the journey to this success was hardly a smooth ride. Dinabandhu Mitra’s Nildarpan was chosen to be the first performance with tickets. The name of the group was changed by then into National Theatre. But one amongst the group of friends raised an objection to the name. The dissenter was none other than Girish Chandra Ghosh. Later, Girish Chandra himself described his disapproval in following words, ‘by giving the name National Theatre and simultaneously performing in front of the audience without the deserving props of a national level theatre, resulted in my immediate objection. The other regional people of India had already started mocking the Bengalis, and in this very context the displaying of our own poverty in our productions could only lead to more such mockery– and that was the primary reason for my displeasure at the name.’ But the other members of the group did not pay heed to this and continued with whatever little could be mustered. This however led to the unfortunate departure of Girish Chandra from the group, while the show continued without him.

The organisers categorised the audience seats into three classes, based on the price of tickets. The first class was decorated with the rented chairs, the second one with the benches on wooden plank on a bamboo structure, and the third class had only stairs. The first night of the first show, sold tickets worth two hundred rupees.

Praise for the production values and acting seen in Nildarpan flooded contemporary newspapers that would not have been missed by Girish Chandra. However, in the year 1972 on the dates of 19th and 27th December two anonymous letters were published in the publication Indian Mirror which went on to severely mock the play Nildarpan. The identity of the writer was however veiled under the name of ‘A Father’ and ‘A Spectator.’ It was rumoured that Girish Chandra was in fact the writer who had written penned the critique.

Nildarpan was staged twice, although between the first and the second shows, another play named Jamai Barik was staged too. Besides, Sadhabar Ekadashi, Nabin Tapaswini, Lilabati, and Biye Pa gla Buro had also been produced. The success of the National Theatre compelled Girish Chandra to return to the old fold. The performance of Krishnakumari, in the play by Michael marked his comeback. Nevertheless, the team hid his name during the promotion.

Surprisingly though, the successful run by National Theatre was abruptly stopped in six months. After the staging of Buro Shaliker Ghare Ro and Jemon Kormo Temon Fol the first session of the commercial theatre ended. The reason for this was cited as the beginning of the monsoons which led to the flooding of the premises of the Sanyal House where the plays were staged.

Soon however, armed with the new name of Oriental Theatre, many shows were held in the house of Krishna Chandra Deb. During this period Sharat Chandra Ghosh, the grandson of the famous Chatubabu (Ashutosh Deb) of Calcutta, founded a committee of intellectuals. As a part of this, a theatre group named Bengal Theatre was formed. Vidyasagar and Michael Madhusudan were among the intellectuals who graced the committee. This was the first time when the group had their very own theatre hall for their performances. With the staging of Michael’s play Sharmishtha, the Bengal Theatre began its journey in August 1873. For many such reasons, Bengal Theatre holds a prominent place in the history of commercial theatre in India. It was also here, that for the first time, women played the roles of female characters, instead of men taking their place. There were other exceptional times like Jagat Singha, while acting in Durgeshnandini, Sharatchandra Ghosh used to appear on the stage riding a real horse. Bengal Theatre survived till 1908.

With the uncertainty of renting people’s houses came the idea of the security and longevity of owning a private theatre hall, and the success of Bengal Theatre led Dharamdas Sur to build Great National Theatre on the very spot where Minerva Theatre stands to this day. However, a fire broke out on the very first night of the show, but in spite of this initial setback, it still managed to go on for four years. The theatre house was not without its share of controversies too. One of the productions from this theatre house mocked the English people, which in turn led to the application of the Dramatic Performance Control bill, which evolved into the Act of 1876 consequently cutting off much of the freedom of theatre performances.

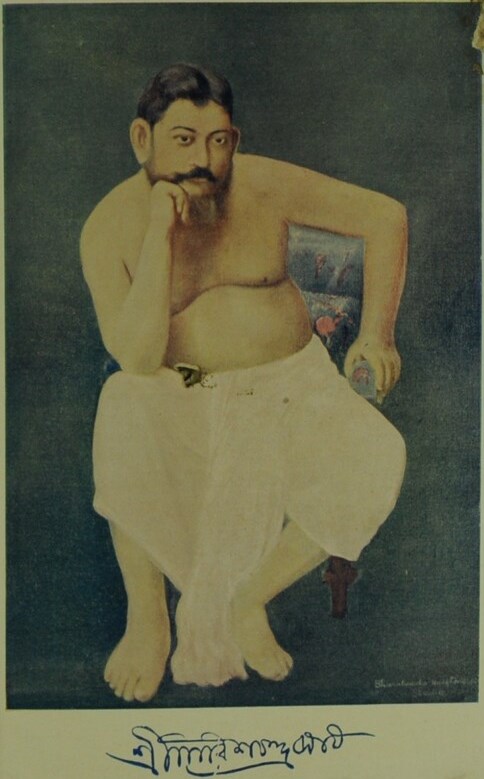

Around 1877 Girish Ghosh brought the lease of the Great National Theatre, and for the next three years he ruled as the undisputed ruler of Bengali commercial theatre. During this period, he also nourished the rather nascent Bengal theatre into a more mature capacity. It was a time of flourishment of his own acting abilities as well. Ghosh composed plays (some of which were anonymously done too), acted in plays, taught others to act, and donated his hard-earned money for the cause of theatre. He also bought affluent personality Gopal Lal Shil’s property and established Emerald Theatre. Gopal Lal Shil appointed Girish Ghosh as his manager with Rupees twenty thousand and a bonus stipend worth three hundred rupees a month. From this amount, Girish Ghosh donated Rupees sixteen thousand to the owners of Star for erecting a new theatre house. Gopal Shil had an agreement with Girish Ghosh that he would not share his plays with any other theatre house. To avoid this condition, Girish Ghosh began writing anonymously and continued providing the Star with his plays for their performances. There is no other example of such selfless contribution in theatre as that of Girish Ghosh in the trying to expand and improvise that status of commercial theatre in India. This period is aptly known after him as the era of Girish Ghosh.

During this time, there sprouted another trend. Young men from wealthy homes started spending their money on theatre, and there came to be places where the petty gimmicks overtook the real effort of acting. Theatres groups began mushrooming everywhere, but were mostly lost in oblivion in no time because of their poor standards. During this time, several non-Bengalis began exhibiting their interest in investing in theatres, thinking it would lead to a profitable business. In this, Girish Ghosh pushed them a lot too, though there was the other appeal of getting to know theatre personalities, especially the attractive actresses who frequented this field. Because he had to pay attention towards the establishment and management of the theatre business, Girish Gosh did not have enough time to devote towards the subtle aspects of theatre and acting. He had tried to create a template that focussed on the successful running of a theatre, while trying to educate people on how theatre could be a profitable business.

During those days, plays were usually long and filled with various subplots. Shows would go on throughout the night. Most of these plays would be replete with song and dance sequences, that helped in capturing audience’s attention. For the very same purpose grandiose costumes were used too, mostly without any justification to the storyline of the play. Drawing the attention of the audience had become the primary approach of Bengali theatre for a while, till the appearance of Sisir Kumar Bhaduri in this area, which led to subsequent changes in the course of Bengali theatre.

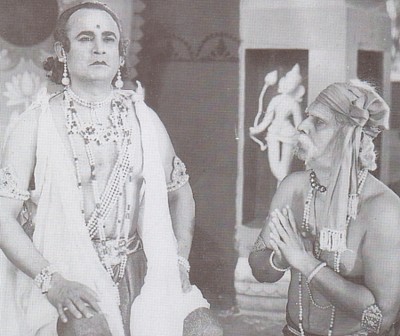

Soon, almost an educational change appeared within the walls of theatre, with an overall uniformity. The taste of theatre came to be elevated to a higher form. Thanks to the efforts of Sisir Kumar, and a few other educated personalities such as Rakhaldas Bandopadhyay and Suniti Kumar Chattopadhay, a certain class came to be associated with theatre both directly and indirectly. Sisir Kumar Bhaduri moulded the stature of theatre to such an extent that the educated middle-class Bengali accepted the new norm by eradicating all previous understanding of theatre as uncultured road that halted the progress of theatre. The personality and stature of Sisir Kumar led to the introduction of the first ever educated woman- a graduate- Kankabati Sahu, to join the stage. Kankabati Sahu’s joining the stage was of tremendous significance. In many ways, it set an example for other educated middle-class women to join theatre in the future.

One could notice by now, that the mass perspective about theatre had already started changing. This in turn also changed the character of the audience’s frequenting theatre shows. Slowly, an educated environment began emerging around theatre. One could summarise, by saying that the model of theatre one is accustomed to seeing in modern times in Bengal, can be attributed to the contributions of Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. If Girish holds the position of being the father and the protective guardian of theatre during its teenage years, then it was Sisir Kumar Bhaduri who must be accredited as the one who moulded and steered the direction of this theatre’s youth, while also bestowing on it a well-deserved social status. This period is still known as the age of Sisir.

But it would be unjust if we do not acknowledge the influence or presence of many others in this journey, while acknowledging the immense role played by both Girish Ghosh and Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. One such instance comes to the mind, when in 1884 Sri Ramakrishna attended the Star Theatre show of Chaitanya Leela, in order to watch Binodini act in the play. This incident of his attending a play, gave a major boost in in terms of social approval, to the otherwise maligned and underrated world of commercial theatre.

None of the founders of the commercial theatre thought of theatre as a mode of earning money neither did, they look at it as a career option. Commercial theatre started with idea of selling tickets to cover the expenditure of theatre production costs and to create a space for the mass audiences to enjoy a show. This could also be seen as a wish to spearhead the rise of a middle class cultural identity amongst Bengalis, as opposed to that of anglicised upper class “Babu” culture propagated by the affluent British loving sections of the society.

But Girish Ghosh realised early on that theatre could not survive by such ideals. He believed that for running a theatre, one must have some idea of business, which he himself possessed due to his experience in the job of a book keeper. This much needed realistic vision blurred all other idealistic notions as a result. Girish Ghosh went on to establish a form of theatre where he gave birth to the concept of the manager-actor. In his case of course, it was that of a playwright-manager cum actor. Incidentally both Dinabandhu Mitra and Madhusudan Dutta died within the gap of a few months, which proved to be shocking to the nascent theatre world even while there was an increasing urge amongst people to watch more plays. In this scenario Girish Ghosh had no other choice but to write his own plays, because of the primary need for script for running a theatre house.

While it might be noted here that Sisir Kumar tried to improve on the quality of acting and other nuances of theatre, which Ghosh could not pay attention to, unfortunately, he too, was embroiled with the same problems. In order to improve the craft of theatre, one needs enough liberty, which could happen only with the privilege of owning a personal theatre. But the same vicious circle continued here too, on owning a private theatre, the emphasis of the actor or director began to be focussed on earning money. It was often seen that this desire sparked the subtle struggle between business and art. Instead of complementing each other, they evolved into rivals. Unfortunately, this unfair struggle spelled the death knell for both halves of the theatre and its business. Perhaps this came to be one of the biggest reasons for the dramatic decline of commercial theatre.

Sisir Kumar Bhaduri had to forego commercial theatre in the year 1956. He was no longer capable of paying his residential rent. Meanwhile, the Gananatya Sangha had arrived with Sambhu Mitra and Bijan Bhattacharya at its helm. Once again, the very orientation of commercial theatre changed its course. Though it was obvious that the glorious era of commercial theatre had ended with the decline of Sisir Kumar, it still managed to survive for two more decades. Mahendra Gupta till his last days kept performing in Star Theatre, while Uttam Kumar acted in Shyamoli that had a blockbuster run for days. Sarkarina or Biswanath Mancha, Rangmahal or Asim Chakravarty – all of them tried to save commercial theatre by introducing various exciting elements, but the primary financial problem clogged its progress. Utpal Dutta and Ajitesh Bandopadhyay tried the same for a period too but these weren’t very fruitful experiments in the long run.

Therefore, after one hundred and fifty years, all that remains of the commercial theatre seems to be bare memories.

***

Translator’s Bio:

Armaan Singh has jointly translated Prabal Kumar’s poetry along with Barnali Roy. He is currently working on a translation of a Bengali novel. He is also into book editing and cover design.

Image Sources:

Cover

Sisir Kumar Bhaduri

Girish Chandra Ghosh