From the Editor’s Desk

At the 49th International Kolkata Book Fair last month, I was happy to note the presence of a robust number of literary magazines. Bengal(in India) boasts of more than 3000 little magazines, most of which are privately funded and run by literary minded friends or communities who felt the need to voice their opinions through a literary magazine. At a time when, like everything else, literature too seems to be devoid of individuality, it is the little magazines that seem to have retained the power to say things differently.

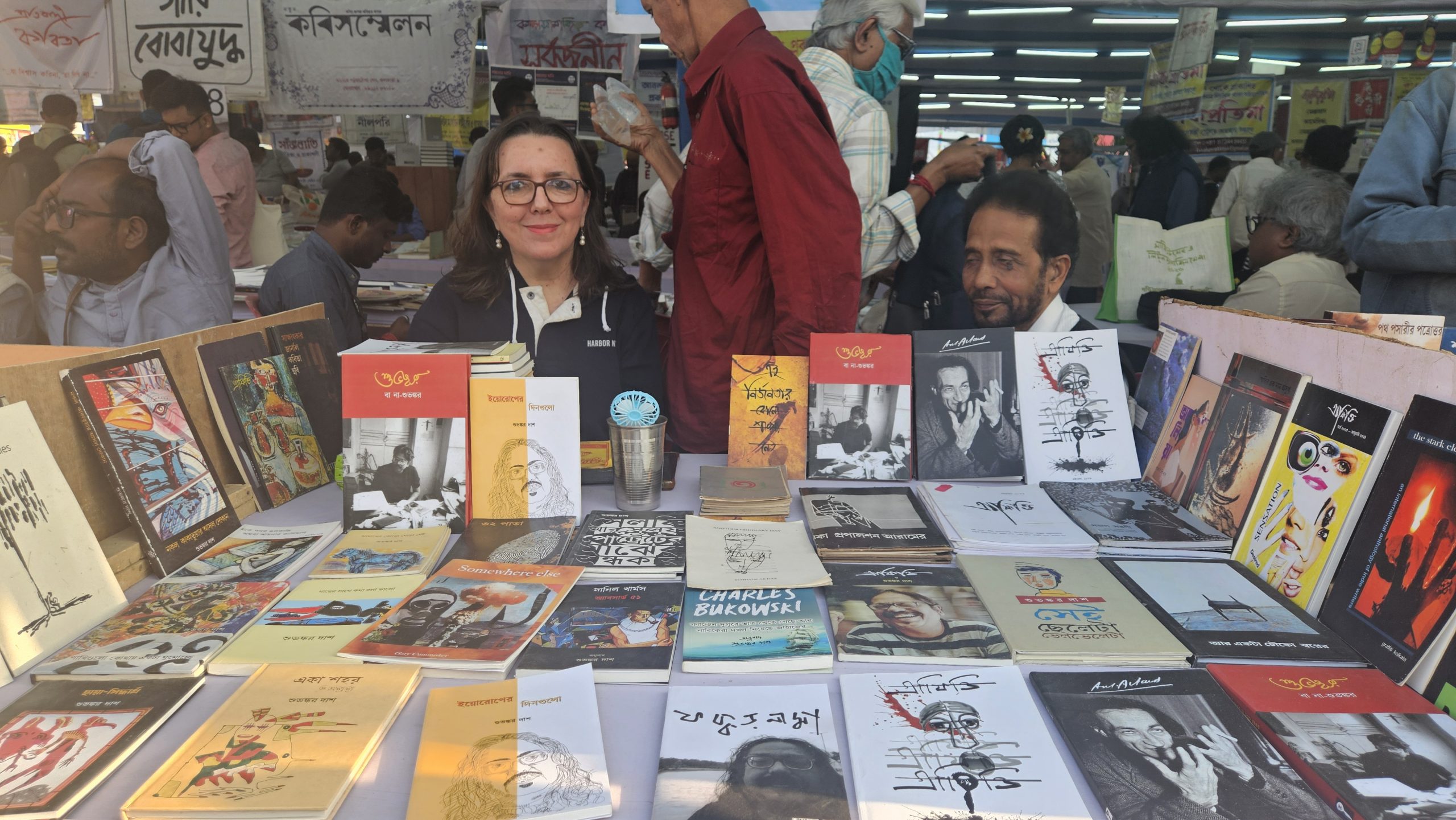

Here there's no hierarchy, no competition for publicity, and literature can be shed of the formality that big publishing often finds itself caved into. Wading through the maze of different stalls, some of which now also bring out literary memorabilia, calendars, posters and even hand drawn sketches- one is filled with a sense of awe and wonder at the sheer scale of this private enterprise really! Another interesting feature of these little magazines is collaborations with writers, especially poets from all over the world, and publishing their work here both in English and Bangla. I found books by American poet Howie Good and South African poet Gary Cummiskey in the stall by 'Graffiti Kolkata', a magazine that was started by Bengali poet Shubhankar Das, highlighting experimental writing from all over the world. Graffiti is now helmed by Das's wife Sabina Pandey, after his passing away.

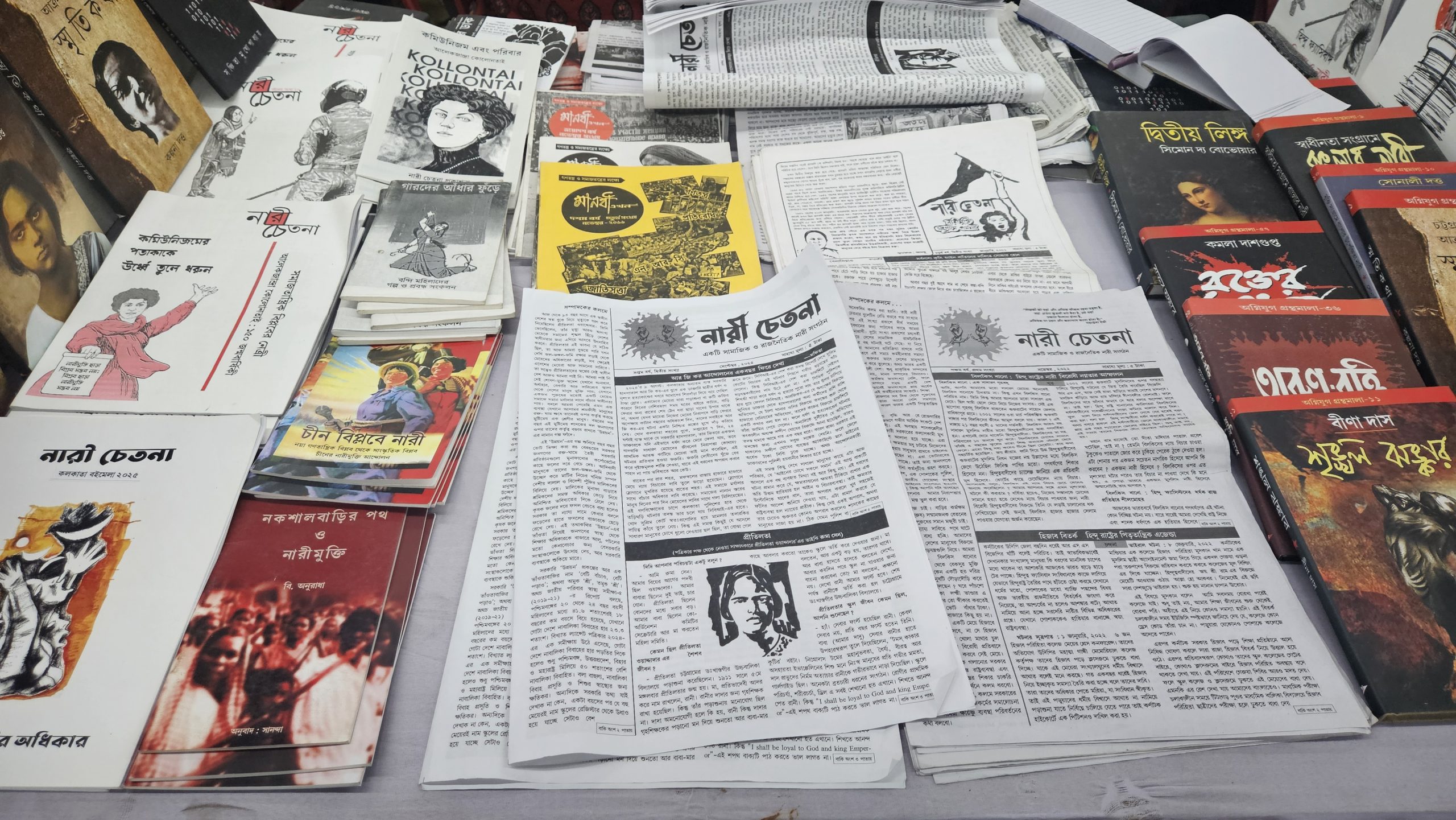

Sabina spoke to me about other women like her, who were also running magazines. Sanchita from the 'Nari Chetona' little magazine stall spoke to me about the gender related issues tackled by the magazine, their stance and perspective regarding the issues faced by women in the country now. There were other magazines like, 'Ahalya' or 'Shiu', published by women, and dealing with sensitive issues related to gender. In that sense and more, the Little Magazine voice, especially in the vernacular, feels distinctly different, even bold, and definitely experimental.

In preserving this spirit of experimentation, of being able to tell different stories, we bring you another issue of The Bangalore Review dear readers. Enjoy.

Maitreyee Bhattacharjee Chowdhury

Managing Editor, The Bangalore Review