A few days ago, I scheduled a visit to the Kolkata Little Magazine Archive in Tamer Lane, in the college Street area. A private initiative by Sandip Dutta (an erstwhile school teacher), who turned his private collection of 750 magazines (in the late ‘70s) into nearly 70,000 (at recent count). Completely driven by this one man’s initiative to preserve the little magazines, this place has grown into a unique library as well as a resource centre, certainly one of the rarest of its kind in the country.

As a country, we have a rich tradition of little magazines, published in various Indian languages and English. Since the early 1920s, the trend of little magazines started with the desire to talk and write about matters distinctly different from what was communicated through mainstream literary avenues. As a result, a platform was created by these magazines to showcase an eclectic mix of experimental Avant-Garde literature, colloquial language trends, and controversial socio-cultural issues. Soon enough, new movements and unpopular ideas found a home here too.

In Bengal particularly, considering the fact that the political voice and that of the revolutionary, almost always begin from literary stables, the little magazine publishing soon turned into a movement of sorts, especially around the 1950s-1970s, and more importantly, acquired a political outlook. Interestingly enough, the movement did not confine itself to literature and politics, but soon turned into platforms for dissemination of fresh scientific ideas that sought to break the old mould, even taking on the role of educating people.

Around this time, people’s theatre groups had become popular, and their experiments were often recorded in the little magazines that were part of these theatre groups. Many of these magazines were individually edited or supported by theatre and even film personalities/film makers. They used it as a platform to interact with their viewers, sharing new ideas regarding experimental filmmaking and a new mould of theatre. Names like Utpal Dutt and Ritwik Ghatak come to one’s mind in this regard.

The oeuvre of the little magazine movement began showcasing fresh trends, protest culture, and especially turned vocal against the growing culture of excess. In this sense and more perhaps, the word ‘little’ itself became symbolic, for calling out the Big world of the mediocre and boring. The trend of little magazines led to healthy discussions carried beyond the pages of the magazines into the living rooms of people’s homes.

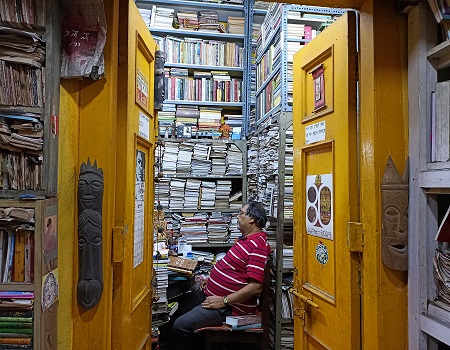

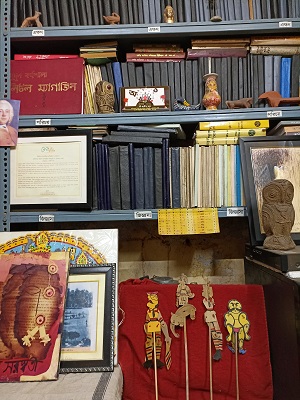

Kolkata in the month of May is terribly hot and humid, and as I walked through the maze of College Street lanes to reach my destination, there was no sight of rain or respite from the heat. However, as I stood outside the brightly painted yellow building that houses the archive, the heat of May gave way to an inevitable sense of history that surrounded the place. As I walked into the part home, part library of the Dutta’s ancestral home, I found him seated in a wooden chair right in the centre of the room, talking to a few research students. This smallish middle room is flanked by two tiny corner rooms, every inch of the wall covered in shelves that house thousands of magazines, as well as a small collection of terracotta dolls and other curios that he has collected over the years. In the centre of the room was a table, where an octogenarian, supposedly one of the oldest members of the library, sat reading a magazine.

Mr. Dutta, isn’t comfortable with interviews. “I prefer an adda,”he said with a laugh. “These are all stories, aren’t they? One flows through the others, with little structure.” I agreed with him, and we sat down to a long winding discussion. We traversed through the lanes of Dutta’s memory as he talked about the culture of little magazines. He expressed anger at the mishandling of little magazines he witnessed at the hallowed National Library (Kolkata) when he visited the place as a young student. The experience led to his determination to open a specific library for these magazines.

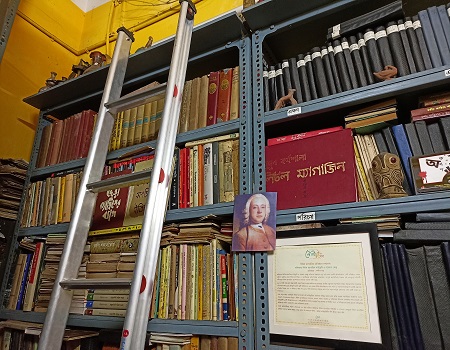

The talk turned to his struggles at rehabilitating the magazine premises into a larger space, worries about the future, and unflagging enthusiasm about running the place. Dutta was clear about his reluctance to hand over the place to either the government or industrialists, both of whom, he says would mess up the character of the place. “Ideally, it should be run by book lovers, archivists, researchers, people who value and understand the relevance of what I have here. The categorisation itself is a huge task. I wanted to stock rare materials and widely experimental journals. As such, the categories we maintain here are vastly different from what you would find in other libraries.” Sexuality, poetry, travel and tribal literature in little magazines—these are just a few of the sections he told me about—it is obviously an exhaustive list, one which he has curated with much deliberation. This also brings me to the subject of curation; I asked him whether he had begun stocking the magazines with specific areas in mind? “Initially, it was not so. Some of them were, of course, deliberate choices, which I collected out of enthusiasm, and which later fell into one category or the other. For some, a pattern emerged, while availability was a determining factor for a few publications. But the joy of finding a rare little magazine still excites me.”

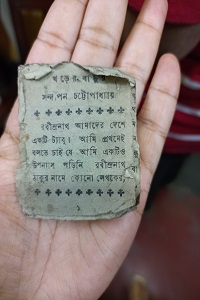

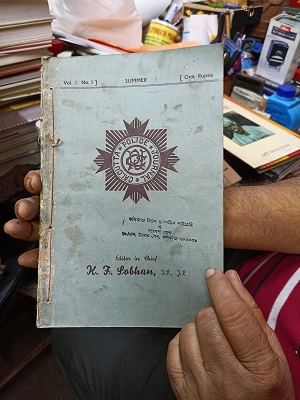

With great pride, I was taken around and shown some of the tiniest and the rarest magazines you might ever come across. A Calcutta Police Journal from the British days occupies pride of place—photographs of culprits, the punishment given to them, stories by the policemen and advice, spans the yellowed pages of this first edition. Dutta showed me a pen, on the body of which, is written an entire poem! There was an entire journal in miniature form written on neatly cut and bound pages, small enough to hold in one’s palm, and yet another on an actual palm leaf. He tells me how his passion was fuelled by the fact that he lived through the Sixties, a time when the little magazine movement especially flourished in India, especially in the states of Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, and of course West Bengal. “There are so many good magazines which had to shut down, either because of the lack of funding or because they were far ahead of the times. But what is very interesting is that these magazines weren’t really looking at publishing well-known names or a certain type of writing. In that, these magazines were truly avant-garde.”

Slowly and tenderly, he took out the inaugural edition of Bangadarshan, first published in 1872 by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay. It is the only surviving copy in the public domain. Mr. Dutta also has the complete editions of Sama Samayik, a little magazine that Nirad C. Chaudhuri had edited during the 1950s.

Despite Mr. Dutta’s almost single-handed contribution to the library, the place has managed to gain a legal and institutional entity. It is now known as Kalikata Little Magazine Library O Gobeshana Kendra (Kolkata Little Magazine Library and Research Centre). The library now has a regular membership, many of whom are life members. The fee structure takes care of some of the money that goes into the upkeep of the place, even though it would hardly be enough.

When I quizzed Mr. Dutta whether he was a writer himself, he laughed it off. But he admitted that he used to write, but now he devoted most of his time to the library. “I read poetry. At one point, we would have poetry readings here, later, story readings were added too. The funny thing was that in Kolkata, there was more poetry being published than the number of readers! We have had so many interesting people here, writers, researchers, filmmakers. The list is endless. You see, little magazines are special; they are unlike commercial magazines, and so are the people who read them.”

While on the topic of magazines, we cannot leave out the presence of online magazines. Given the fact that a generous grant from the Bangalore-based institution IFA (India Foundation for the Arts) has helped partially digitize some of the oldest magazines in his library, what does he think of online magazines?

“It takes away much of the joy for me. There’s no denying the fact that it helps in the process of archiving, but I’d much rather see people come in here and read.”

The afternoon passed in stories and anecdotes from the past and present, including some about writers, others about famous personalities like veteran actor Soumitra Chatterjeeand Nirmalya Acharya, who edited the very popular little magazine Ekshan—the back stories about the process of editing and much more.

By the time I said goodbye, it was evening. I felt as if I had been in the midst of good friends. As I walked out, making way for a few more students walking in starry-eyed, I felt confident that the archive would live on in some manner or the other. To the lovers of experimental literature, the task of carrying on this legacy now lies bequeathed.

Images by the Author