The smear of blood stretched from Evelyn’s property across the cul-de-sac and into the desert beyond. It had mostly gone brown, baked there by the afternoon sun, but there was enough in the middle to still be thick and wet. The red of it cartoonish in its brightness.

“We’ve already called the county. They’ll remove the carcass.”

“Carcass is a good word,” Evelyn thinks but does not say. She moved into the house only two years before and lived there now with her little girls, ages two and five. New Mexico was new to them—they’d lived last on the East Coast in a state that fit in New Mexico’s pocket—and they’d been told the East Mountains would be safer than the city of Albuquerque where every house had bars on the windows. They’d found a neighborhood of sorts in the Sandias, and it had taken only three months for Evelyn to wish for bars on the windows.

“Can I see it?” she asked her neighbor. She thought his name was probably Frank, but it might have also been Al or Tod. She couldn’t remember. He had a wife she’d never even seen, let alone met. People moved to the Sandias to be left almost entirely alone, and that was even more true post-pandemic, so she’d only met Frank/Al/Tod once before when she’d briefly adopted a dog that had barked at him. Evelyn had to apologize profusely, returning the dog to the pound shortly after realizing “one too many things on my plate” was an understatement.

“Of course,” he said. “Round the back.”

He was her age, this neighbor of no or many names. Good skin, not cracked and red like other white folks who moved to New Mexico. They were at altitude—7,000 feet—and both her kids had multiple sun burns before she realized what hours to keep them in and how often to apply sunblock. Their noses bled all the time, mostly at night, and she’d purchased all new sheets more than once until settling in and accepting that their pillows and cases were going to be a rusty red—pinkish at best—no matter what she did.

Her neighbor was tall. Not thin. Muscled, she thought, but his shoulders were too narrow. And he rode his bike far too much. He was brave and stupid—two things that went hand in hand these days. Always heading out in the morning and coming back hours later, looking somehow no worse for the wear. She’d seen him when she’d gone for her last grocery store run. He’d been on the stretch of road between Golden and Madrid where all the animal crossing signs were stickered with flying saucers, as if there was no telling what one might find in the high desert.

Most days Evelyn couldn’t fathom the heat. The dirt of it. The wind that blew it all around but never seemed to cool any surfaces. She stayed inside where it was temperate and safe. This little venture with her neighbor was the first time she’d left her house in weeks—except for supply runs, of course. The girls, already asleep in her bed, wouldn’t even know she was gone.

“The sun is already setting,” she said. The sky turning pink. To Evelyn, the sunsets were as unfathomable as the summer heat. Tonight, like all nights, the fluff and streak of all that pink stopped her in her tracks. There was a red to it, a smear that reminded her of the cul-de-sac and her children’s bloody noses and the pavement along the busy mile of highway where that SUV had dragged her husband and his motorcycle.

Frank/Al/Tod—she decides to pick Frank next time she needs to say his name—stops to watch the sky with her but then moves on. Evelyn is glad to follow him, her brain too full of gore. She remembers those first hikes they took as a family when they first moved to the mountains before her husband died.

“Keep up!” her husband had said. “One foot after another.”

“They bury it,” her neighbor said. “Shallow but still. They like to kill it and then store it so that they can come back later to snack on it whenever they want.”

Evelyn follows him across the remaining half of the cul-de-sac (past a spot where the blood shone like nail polish), down his driveway, and then into the red, dusty yard to the back of his house.

“Lucky us,” she said.

“I caught the mountain lion on camera. I can send over the video if you’re curious. He seemed intact. No afflictions, I mean, but it was a bit dark so hard to tell.”

“That’s okay,” she says too quickly.

“It’s not footage of the kill. That probably happened on your property. It’s of the mountain lion burying the deer. You can see how she digs, buries it, and looks around to make sure no one is watching. It’s almost human, really.”

This sent a chill through Evelyn. The forest surrounding the Crest Road caught fire shortly after her husband died and then the floods washed what was left down the mountain. Their neighborhood had been spared, but a lot of other places were lost to fire or water or both. The pandemic came on the heels of the flood, and while it hit people as a harsher form of the flu, it was easily passed to animals or from animals to humans—that still wasn’t clear—and it did something genetic to mammals that lived out in the wild. Changed their DNA.

Grief and fear seemed a rational response to the world these days so Evelyn’s little family got by on what they could and rarely left their home.

Evelyn could see the dip of the arroyo ahead. The juniper trees beyond that.

Frank had a patio behind his house, and like all New Mexican patios, it was surrounded by a faux adobe wall. There were four, bright blue metal chairs that Evelyn liked almost enough to ask where he got them, but then again, they were all tipped over, as if they hadn’t been used in forever. She never sat outside either, so what was the good of even admiring them?

They were back in the desert, following a trail that had clearly been made by the dragging of a body.

“Poor thing,” Evelyn said even before they’d come up to the burial site. She felt sad but also curious. Called to the spot. A kind of hot feeling radiating out from her belly. Her mouth filled with saliva.

The woman who had accidentally hooked her back bumper to Evelyn’s husband’s motorcycle was in her 70s. She had six grandkids and no prior record. Evelyn wasn’t allowed to actually talk to her because of the lawsuit, but she’d done some online research. She’d been looking for a reason to hate the woman more than she already did, but it had the opposite effect. This woman had once liked to hike with her friends, eat ice cream with her grandchildren, and donate her time at Animal Humane. Now, of course, she stayed home. Even in the city, the landscape had changed.

Evelyn and her now-dead husband had fought the morning before the accident about who would cook dinner or buy groceries or get up in the night if the baby woke up again. He’d left without all the usual gear—armored pants and jacket left behind in favor of a t-shirt and jeans. He’d grabbed an old helmet, the one closest to the garage door, and so when the lady hit him, he’d had little to no chance of emerging uninjured. She didn’t even notice she’d gained a passenger—it turned out she was practically deaf and without her hearing aid. His body separated first and then his bike. Both spun off into the median.

“Jesus,” Evelyn said, seeing the animal for the first time.

The deer’s head looked normal, peeking up out of the red dirt, tongue lolling thickly out of its mouth. The torso was mostly covered as was its tail end, but its legs were visible, four of them and they weren’t hooves as one would expect but rather soft little mounds that looked like curled fists, the nubs raw from running on hot earth. Goatheads clogged the crevices where the digits would develop given more time.

Animals in the area had begun to grow hands, opposable thumbs in fact, while the rest of their bodies remained the same. They’d heard bobcats and coyotes howling off in the distance, maybe on the now mostly abandoned golf course. Many animals couldn’t survive with the new appendages. She’d come upon one of the coyotes about a year ago when she’d risked a neighborhood walk. Its body barely still breathing, ribs about to poke through its skin and its paws turned into bloody digits unprepared for galloping. The deer had the start of fingers, little petals ready to burst open but the mountain lion had gotten him first. Evelyn took a step back.

“It’s harmless,” he says, seeing her revulsion. “You haven’t seen one before?”

“No,” she lied. She didn’t want to talk about it and was annoyed with herself for letting him read her so well.

“People are killing them for their deformities,” he said. “Trophies.”

“That’s sad,” she said, but she rather thought she’d like to have one. Or at least touch it.

“People are cruel,” Frank said, and from this Evelyn could guess that he was among those that believed humanity had brought this on themselves. He wasn’t wrong, but she also couldn’t get entirely on board with that either. Afterall, wouldn’t that somehow mean that her husband died alone in the median because of her?

“Let me see if the ranger has called again. I expected him by now.”

Evelyn’s heart beat a little faster in her chest. When she heard the backdoor shut behind him, she stepped closer to the mostly buried beast. Flies buzzed around its big brown eyes, its lashes were short and feathered. Evelyn reached out to stroke an ear. Soft. She shut her eyes and then took her time opening them, looking at its face before she let her eyes move down to where its hooves should have been. Those rounded nubs of dark skin made her shiver. Its front calves, she noticed, had short little spikes—dewclaws?—above the feet. There were several of them on each leg, sharp, more like thorns on a stem or spines on a cactus. She was reaching out to touch one, see how sharp when she heard her name.

“Evie?” It was familiar, the nickname, and also the way it was said like a question. So familiar in fact that she said “yes”before she even looked up to the soft mouth of the deer. Its neck risen a bit from the dirt; its tongue back in its mouth to form her name.

She stayed crouched down. The deer’s eyes darted in its sockets, as if looking through a great dark for her. “Are you there?” he asked.

The cops assured her that her husband had died on impact, but she knew this wasn’t true. She could tell by the twitch of their mouths when they said it, how many times they repeated it to her. He’d lay there, knowing he was dying, for quite some time. The heat beating down, the dust blowing over him, covering bits of him so that when he was found the person calling said they’d found an animal. Something alien but definitely dead that they didn’t want to get too close to. It made her heart hurt, thinking of him there, unrecognizable as human, needing to be held so he could pass.

“I can’t see you,” the deer said. his mouth moving around the words, his head raised. Blood at the corners of his mouth, dust shifting off his neck as he struggled to raise his head higher.

“I’m here,” she said and reached out for the deer’s neck.

“Don’t leave me here,” he said and then rested his head back into the dirt.

“I would never,” she said, and realized she was crying.

As the world had begun to fall apart all around them, Evelyn had told herself her husband was lucky. If he’d lived, he would have seen the earth turn against them. Against even its sweetest creatures. The prairie dogs, the jackrabbits, the deer. And, in a way, their own children.

Evelyn began to dig the dirt away from the deer’s belly. She quickly found that it was saturated around his torso. His guts partially pulled free were hard to sort from the dirt, but she tried. And, as she tried, she heard him grunting, holding his breath as he focused his energy on his hooves. When the tough skin finally began to break free into individual digits, he cried out. It hurt, the changes.

“I’m sorry,” the deer said, but Evelyn knew it was her husband apologizing to her. It was part of what had kept her anger at bay after he died, knowing how mad he would be at himself for leaving them all alone in a collapsing world.

“I know, sweetie. Let’s get this done before Frank gets back.”

Evelyn took the deer’s front hands in hers. They were tough to the touch, but their strength was new. Like the hands of her children, they fit inside of hers, and she could feel their delicate bones. She pulled and pulled, and at first, she didn’t think she could move him but then the back legs, new hands unfurled, gave a little push and they were moving. Retracing the path that the mountain lion had created.

She’d been a powerful woman once. She wasn’t sure when it had been that she’d felt unstoppable, but it had been there in her not so long ago. Pregnancy had made her feel vulnerable, but childbirth had reminded her that her body was infinite. She closed her eyes and the deer’s hands grew in hers until they felt familiar. Large and reassuring. Her husband’s hands.

Evelyn could hear Frank’s backdoor slam shut before he called her name. She did not answer.

Her feet hit the cul-de-sac and then the desert of her property was under her again. The deer’s weight was different, shifting so that she no longer had to drag him but could guide him, walking backwards with both hands clasped to his hands. Eyes still shut, she found a hot spot of land, the spot where the mountain lion first got its teeth in, she thought, and she opened her eyes.

In the faint red of the darkening sky, she saw that her husband was standing in front of her. His naked body as she remembered it. Tall and strong. Daring and certain. She loved him so.

“You can’t give up,” he said.

“Was I giving up?” Evelyn asked. She wanted to lean in and smell him. Put her face on his shoulder, tilt her nose to his neck.

“You were.”

“I was,” she agreed. “I wanted to.”

He shook his head “no” and said, “Things can be taken back. Reversed. Begun again.”

“Some things can’t,” she said, and she knew he knew she meant him.

“You can do this,” he said. “It’s not too late. Keep walking.” He let go of her.

She yelped out loud as his hands left hers. The shock of his absence as sharp as the first moment she’d heard he was gone. She doubled over. Clutched her middle but then the grief became smaller. She got her breath faster and stood tall again.

She watched him leap through her yard. Long strides as his body turned back to all fours, brown fur dark in the growing dusk, hooves thick enough to kick up clouds of sand.

She could hear her toddler crying. Awake and searching for her in the dark.

The pink of the sky was almost gone, and Evelyn remembers that Sandia means watermelon in Spanish. She thinks of the flesh of that fruit as she moves toward her front door. The hard skin and the crisp, wet inside. The way the juice drips down your face and between your fingers. The stickiness of it like blood, and she knows she can do it all again. Be more than two things at once. Powerful and weak. Cautious and brave. She can take and kill and birth and grow. She and her daughters are here now. Present and part of the mountain.

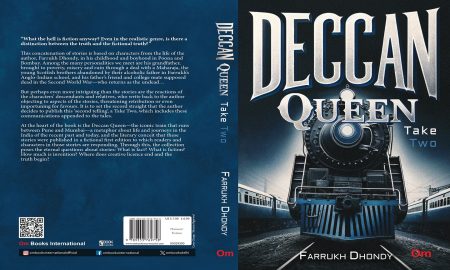

Photo by Ella Baxter on Unsplash