As the severity of summer touches upon the subcontinent, we unravel for our readers translations and works of a poet-diplomat, Abhay K. (currently Indian ambassador to Madagascar) who has in recent times translated some of India’s finest classical poetry by Sanskrit poet Kalidasa. Abhay, has also written much of his own poems- often inspired by his travels as part of his work as a diplomat, his readings of the classics, and remembrance of the India he grew up in, the flora and fauna of the countries that he finds himself working in, and the reflection of these changes both geographically and otherwise on his own sensibilities as a poet. Amongst his recent work, is Monsoon, The Magic of Madagascar, Kalidasa’s translation of Meghadūta and Ṛtusaṃhāra – which received the Kalinga Literary Festival 2020-2021 Poetry Book of the Year Award. His writings cover poetry, art, memoir, global democracy and digital diplomacy. TBR talks to Abhay about his poetry, translations and how his role as a diplomat reflects on his literary output.

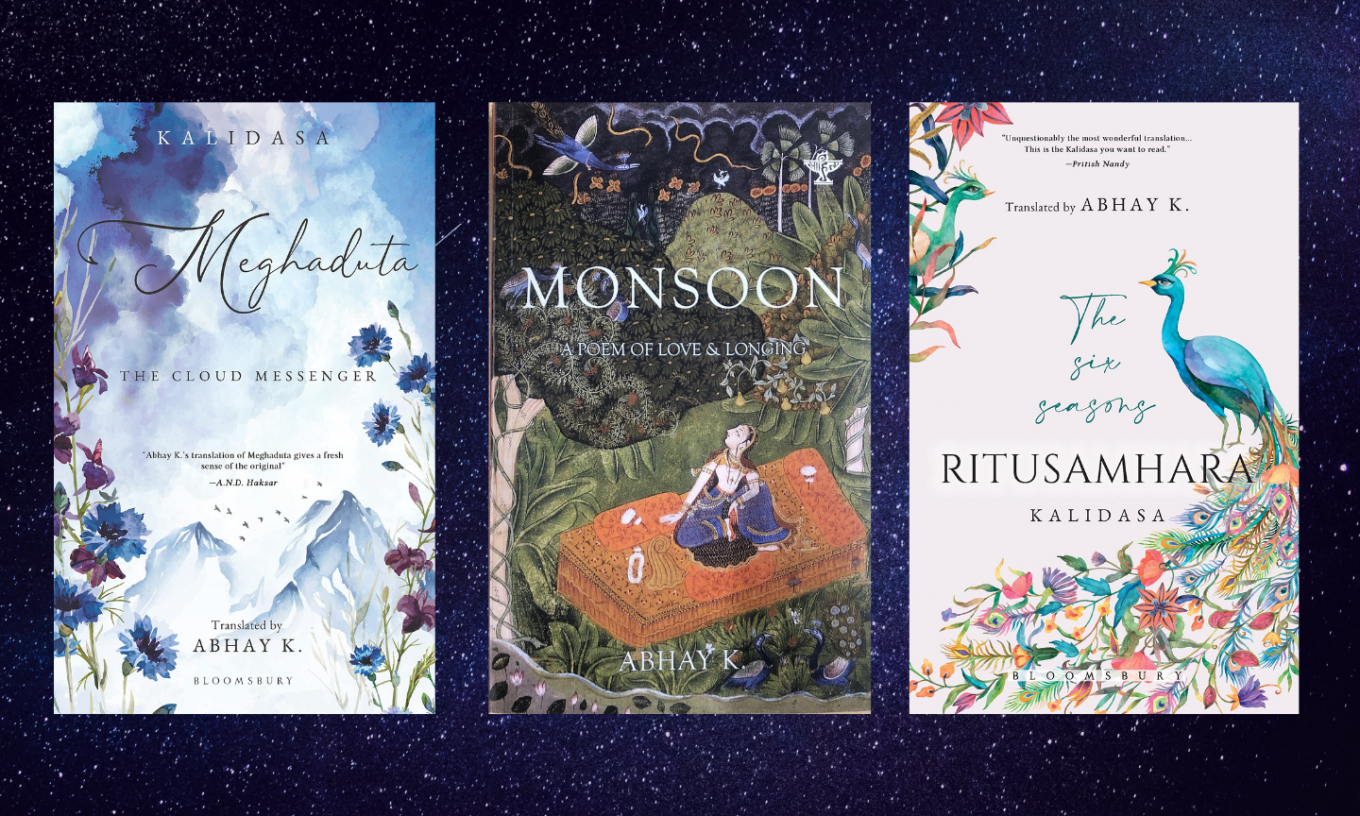

The interview chiefly focuses on his book-length poem Monsoon, and his translations of Meghadūta and Ṛtusaṃhāra.

Kalidasa, known to the world as the classical Sanskrit poet/writer from the (4th-5th century) has a large body of work in both prose and poetry. Other than his plays and works of proses, he is author of epic poems-Kumārasambhava (describing the birth and adolescence of the goddess Pārvatī) and Raghuvaṃśa which describes in details the kings of the Raghu dynasty. Two of Kalidasa’s other, very popular poetic work, comprises the Ṛitusaṃhāra (describing the six seasons by narrating the experiences of two lovers in each of the seasons) and Meghadūta (The Cloud Messenger)- a voluptuous and vibrant elegiac of sorts that tells the story of a Yakṣa(mythological beings of ancient Sri Lanka) trying to send a message to his lover through a cloud.

TBR: You have many books of poems, including the translations of Kalidasa- which form an important part of your oeuvre as a poet, tell us how your own poetry is affected by your role as a translator?

Abhay K.: Some of my poetry collections are The Seduction of Delhi (Bloomsbury, 2014), The Eight-eyed Lord of Kathmandu (Bloomsbury, 2018). The Prophecy of Brasilia (Colletivo Editorial, Brazil, 2019), The Alphabets of Latin America (Bloomsbury, 2020), The Magic of Madagascar (L’Harmattan, Paris, 2021) and the book-length poem Monsoon (Sahitya Akademi, 2022).

I recently translated Kalidasa’s Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger) and Ritusamhara (The Six Seasons), both published by Bloomsbury India in 2021. Translating these two poems had an immense influence on me and inspired me to write a book-length poem Monsoon which has been published recently by Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters). Monsoon draws inspiration from both Meghaduta and Ritusamhara.

Earlier, when I was posted in Brazil (2016-2019), I translated poems of 60 Brazilian poets from Portuguese into English, which were published as New Brazilian Poems (Ibis Libris, Rio de Janeiro, 2019). Translating Brazilian poets helped me to understand the culture and philosophy of Brazil and Latin America and helped me in writing my own poetry collections The Prophecy of Brasilia and The Alphabets of Latin America.

TBR:

Amorous women flirting with their playful moves,

Subtle smiles, stolen glances, and lowered eyes, ignite flames of love

in the hearts of tired travellers like a lovely evening

lit up by the glistening moon.

Kalidasa’s work is replete with Rasa- that evokes an emotional response and helps the transcend time and space in connecting with both pleasure and pain in our minds, and in doing so helping us experience both great joy and agony. Tell us about your experience of it first-hand while you were translating Kalidasa, and also do you feel the presence of this Rasa in contemporary poetry today?

Abhay K.: Both Meghaduta and Ritusamhara focus on nature and sensuous love, the two subjects which do not age. I first began translating Meghaduta and was overwhelmed with its sheer beauty and splendour. I found an immediate connection with the poem being far away from India in Madagascar. Reading these two classics of Kalidasa was timely owing to lockdown around the world making us reflect upon the impact of our actions on the environment. At the same time I was blessed with plenty of nature around me in Madagascar. I internalized everything as if Kalidasa’s Yaksha had entered within me and I started thinking of recreating the same Rasa in my new poem Monsoon as I find very little of it in contemporary poetry.

TBR: In modern times, there have been many books which talk about the secret languages used by trees and animals to communicate with each other. But it seems, Kalidasa could understand this language of nature so many years ago. His world of botanical references, animals, spirits and secrets of the jungle in fact sound very contemporary now. Your thoughts?

Abhay K.: Reading and translating works of Kalidasa has been a pure delight and wonder for me. He comes to me as a contemporary eco-poet writing about nature using the trope of love. Even flowers, plants, animals, seasons, rain, rainbow, wind, sun, moon, stars, stones, rivers, mountains, among other things animate and inanimate have their own sensual personas and feature prominently in Meghaduta. Kalidasa mentions twenty-six different kinds of plants and flowers in Meghaduta such as Mango, Ashoka, Rodhra, various species of Jasmine, Kakubha, Kurbaka, Mandara among others. Women’s physical beauty and sensuality is vividly depicted using metaphors from nature—

Your slender limbs Syama-creepers

your glance the doe’s tremulous eyes

your face the moon

your luxuriant hair the peacock’s tail

your eyebrow play the brook’s ripple

O fair one! you alone have all these

there is no one like you in this world. (101 Meghduta)

As the world faces biodiversity loss of unprecedented scale with around one million species on the verge of extinction, poetry with a strong ecological content has started to take the centre stage of contemporary poetic discourse. New anthologies of eco-poems are getting published every year. Meghaduta is full of detailed descriptions of flora and fauna of the central and north India as well as of their hills, rivers, mountains, legends, beliefs, traditions, mythologies, rituals, sensualities, among others while Ritusamhara is pure ecopoetry.

Kalidasa’s Ritusamhara describes changing life in six seasons—Summer, Monsoon, Autumn, Frost, Winter and Spring, by making reference to a wide variety of flora and fauna and their interaction with the environment. Kalidasa shows high eco-poetic sensibility while describing the plight of animals in different seasons in Ritusamhara and how they come together to support each other during extreme weather conditions while keeping their natural instincts at bay.

TBR: You wrote the Earth Anthem, which was widely circulated during the Earth Day events transcending your message of environment in various languages. What was your inspiration to compose this anthem, and do you think that finally people are listening to poets speaking about environment and its concerns?

Abhay K.: I wrote ‘Earth Anthem’ in 2008 in St. Petersburg, Russia one night, inspired by the Blue Marble image of our planet taken from space by the crew of Apollo 17 and by the ideals of ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ (the whole Earth is a family) from Maha Upanishad. The idea behind writing ‘Earth Anthem’ is to celebrate the beauty and diversity of our planet from a cosmic perspective (Our cosmic oasis, cosmic blue pearl/the most beautiful planet in the universe), express the unity of life on Earth (united we stand as flora and fauna, united we stand as species of one Earth), to emphasize unity in diversity (diverse cultures, beliefs and ways/we are humans, Earth is our home), to show solidarity with one another (all the people and all the nations/one for all and all for one) and to unite us all to give our highest reverence to our planet (united we unfurl the blue marble flag).

Since then ‘Earth Anthem’ has been translated into more than 150 global languages, played at the United Nations in 2020 to mark the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, featured in over 200 publications across the globe including the BBC, The Christian Science Monitor, The Times of India, Khaleej Times and China Daily. UNESCO called it “an idea that can help to bring the world together”, it was performed by the National Symphonic Orchestra of Brazil and the musicians of the Amsterdam Conservatorium, it was set to music by violin maestro Dr. L. Subramaniam and was sung by Kavita Krishnamurthy. Over 100 poets, artists, singers, musicians, professors and people from different walks of life came together to read ‘Earth Anthem’ to mark the 51st Earth Day on 22nd April 2021. It became one of the key global events on this occasion. This year too people across the planet celebrated Earth Day with ‘Earth Anthem’.

Growing interest in Earth Anthem shows that people are listening to poets speaking about environment and its concerns.

TBR: Kalidasa’s work invokes the Shringar Rasa (invocation of beauty) the most, what was the reaction to that, from the readers of your translations, when the book was published, especially outside India?

Abhay K.: That’s true. Here are some stanzas from Meghaduta

Her body dusky, delicate, her teeth like jasmine buds,

her lips ripe bimba fruits, her eyes like a startled deer’s,

she is thin in the middle, her navel deep,

she walks slowly from the heaviness of her hips,

and bends forward a bit because of her breasts—

she is like Brahma’s first creation among the women. 79

Her eyes kohl-less, side glances blocked by stray hair,

her brow play forgotten with abstinence from wine—

the doe-eyed beauty’s left eye would twitch upward

on your arrival, as a blue lotus quivers

from the touch of a fish. 92

And Ritusamhara

Round hips, their beauty augmented

with soft silk and the jeweled belts,

their sandal pasted breasts shining

with strings of pearls, hair fragrant

with subtle and lingering perfumes,

women soothe the senses of their lovers

with these in the scorching summer. 1-4

At the break of the dawn, a young maiden

weary from the night-long love’s delight, scans

her squeezed nipples, her body full of love bites,

and moves around with a suppressed smile. 5-11

My translations of Megahduta and Ritusamhara have been well received both in India and abroad. When I announced the publication of these two translations, it created a buzz in the literary circles. A number of academics from foreign universities wrote to me asking if they can include my translations of Kalidasa’s Meghaduta and Ritusamhara as part of their syllabus.

TBR: You say that the idea of your book, titled Monsoon, stemmed from the wish to write about the annual journey of the monsoon from Madagascar to the Indian subcontinent and back to Madagascar. One finds references of flora and fauna in both countries in the book. Please share a few lines that talk about this essence, and also tell us how the monsoon in both these countries affected your writing.

Abhay K.: South-west Monsoon travels every year from Mascarene High near Madagascar to the Himalayas and back. This annual journey of monsoon from Madagascar to the Indian subcontinent and back to Madagascar set me thinking about writing a love poem that follows the path of the monsoon.

Monsoon is a poem of love and longing wherein a poet in Madagascar exhorts monsoon to take his message, and the sights and sounds of whatever it comes across on its way, to his beloved in the Kashmir Valley in the Himalayas. The poem, a quatrain (Rubāʿī or chāhārgāna) of 150 stanzas, introduces the reader to the rich culture and biodiversity of the islands of Madagascar, Reunion, Mauritius, Seychelles, Mayotte, Comoros, Zanzibar, Socotra, Maldives, Sri Lanka, and Andaman & Nicobar and the Western Ghats, Aravalis, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Sundarbans, West Bengal, Bihar, Sikkim, Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet, Uttarakhand, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir Valley as monsoon passes through these places. Here are some stanzas from Monsoon–

I wake up with your thoughts

your fragrance reaching me

all the way from the Himalayas

to the island of Madagascar 1

brought by monsoon

from the blessed Himalayan valley

to the hills of Antananarivo

on its return journey 2

O’ Monsoon, wave-like mass of air,

the primeval traveller from the sea

to the land in summer, go to my love

in the paradisiacal Himalayan valley 6

lovesick and far away from my beloved,

I beseech you to take my message to her

along with amorous squeals of Vasa parrots,

reverberating songs of Indri Indri 9

the sight of ayes-ayes conjoined blissfully

at midnight in Masoala rainforests

fierce fossas mating boisterously at Kirindy

colourful turtles frolicking in the Emerald Sea 11

upon arriving in idyllic Mauritius

you’ll be greeted by Le Morne Brabant

home to rare Boucle d’oreille and Mandrinette flowers,

rejuvenate them with your rain showers 21

proceed further northwest to the islands of Zanzibar,

Red Colobus , Fischer’s Turaco, Blue Duiker

would be ecstatic, glide past the narrow alleys

of the Stone Town inhaling rich aroma of its spices 36

Nathang valley in Sikkim craves for your soft cuddles

as lovers meeting each other after a long interval,

virgin backwoods, Satyr Tragopan, Himalayan Monal

and red panda await to enchant you at Zuluk 62

upon your arrival in Kashmir

your salubrious rains will infuse new life

in chinar, walnut, almond and pine trees,

the stately hangul will leap in the high valleys 143

Monsoon not only depicts the rich biodiversity of the places but also highlights their vivid colours and sounds, tastes and aroma of the rich cuisine, history and legends, landscapes, monuments, among others. In this poem I have also tried to weave together monsoon inspired architecture, such as the Monsoon Palace in Udaipur, Badal Mahal or Cloud Palace in Kumbhalgarh, Anup Talao at Fatehpur Sikri where Tansen used to sing his Megh Malhar, Deeg Palace near Bharatpur with its nine hundred fountains trying to recreate monsoon rains, the monsoon festivals of Haryali Amavasya and Teej and the forgotten 17th century monsoon raga Gaund which was once popular in the court of Mughal emperor Shah Alam.

Monsoon is homage to the rich natural world of the Indian Ocean islands and the Indian subcontinent, their vibrant cultures and traditions and to the great Kalidasa who gave us Meghaduta and Ritusamhara.

TBR: What are your thoughts on the religious, cultural and social significance of Kalidasa’s work today, with regards to an understanding of the heritage of the subcontinent, as well as its influence on your own profession as an Ambassador of India?

Abhay K.: The secret of Kalidasa’s continued relevance even today rests on his focus on nature’s beauty and sensuous love, the two subjects which are of great interest to us, and his genius in making these two flow into each other seamlessly. Kalidasa’s works should be of great interest to contemporary readers as we deal with biodiversity loss and climate change today. Can we use the image of nature as a sensuous being presented by Kalidasa in Meghaduta to transform how we see nature—from mother to beloved, from revering it to loving it and from being separate from it to being part of it? Can it help us in protecting nature if we start to see clouds, rivers, plants, trees and animals as sensuous beings?

Kalidasa also highlights the importance of nature in our love-life, without which we would gradually become bio-robots obsessed with numbers and statistics, dealing with various kinds of growth rates, and living a dismal life on a planet devoid of biodiversity and marred by extreme climatic events.

Lockdown across the planet has taught us to pay attention to our surroundings as Kalidasa has done in his Meghaduta and Ritusamhara, reminding us of all the beauty waiting to be discovered by slowing down, listening to birdsong, smelling the fragrance of flowers, reading books, thinking about our relationship with the nature and how to tackle the three biggest challenges our planet faces today—biodiversity loss, climate change and environmental pollution.

German philosopher Martin Heidegger thought that the function of poetry is to save the Earth from the consequences of an instrumental or technological attitude towards nature. Kalidasa’s poetry does exactly that.

I have not come across any other poet who describes the lives of antelopes, peacocks, boars, lions, elephants, cobras, frogs and buffaloes in such detail and with such empathy. As we face the threats to our existence owing to our ever growing greed and the culture of consumerism, we may lose what makes us human. It is in these unprecedented times, reading and re-reading Kalidasa becomes essential.

Reading and translating the works of Kalidasa inspired me to create a literary bridge between Madagascar and other Indian Ocean islands and the Indian subcontinent through Monsoon, which I believe is an important dimension of cultural diplomacy.