The Yellow Notebook is from Aamer Hussein’s anthology, Restless. The book is a collage of fugitive fictions, reminiscences of friends, and personal essays which, when read in sequence, offer an unofficial picture of one writer’s private and public lives.

Read a connected short story, The Garden Spy, from the same collection here.

We’d just ended a discussion on the telephone, of what we were going to include in my new book, when I came upon a photograph of some flowers you gave my mother exactly two years ago. A day later I found photographs of swans we took together in Windsor. So many of my memories of times spent with you are linked to water: the canal by my house on the first of our many London meetings, the seaside in Karachi where you wanted to photograph me for the jacket of Hermitage, the river in Windsor two winters ago…

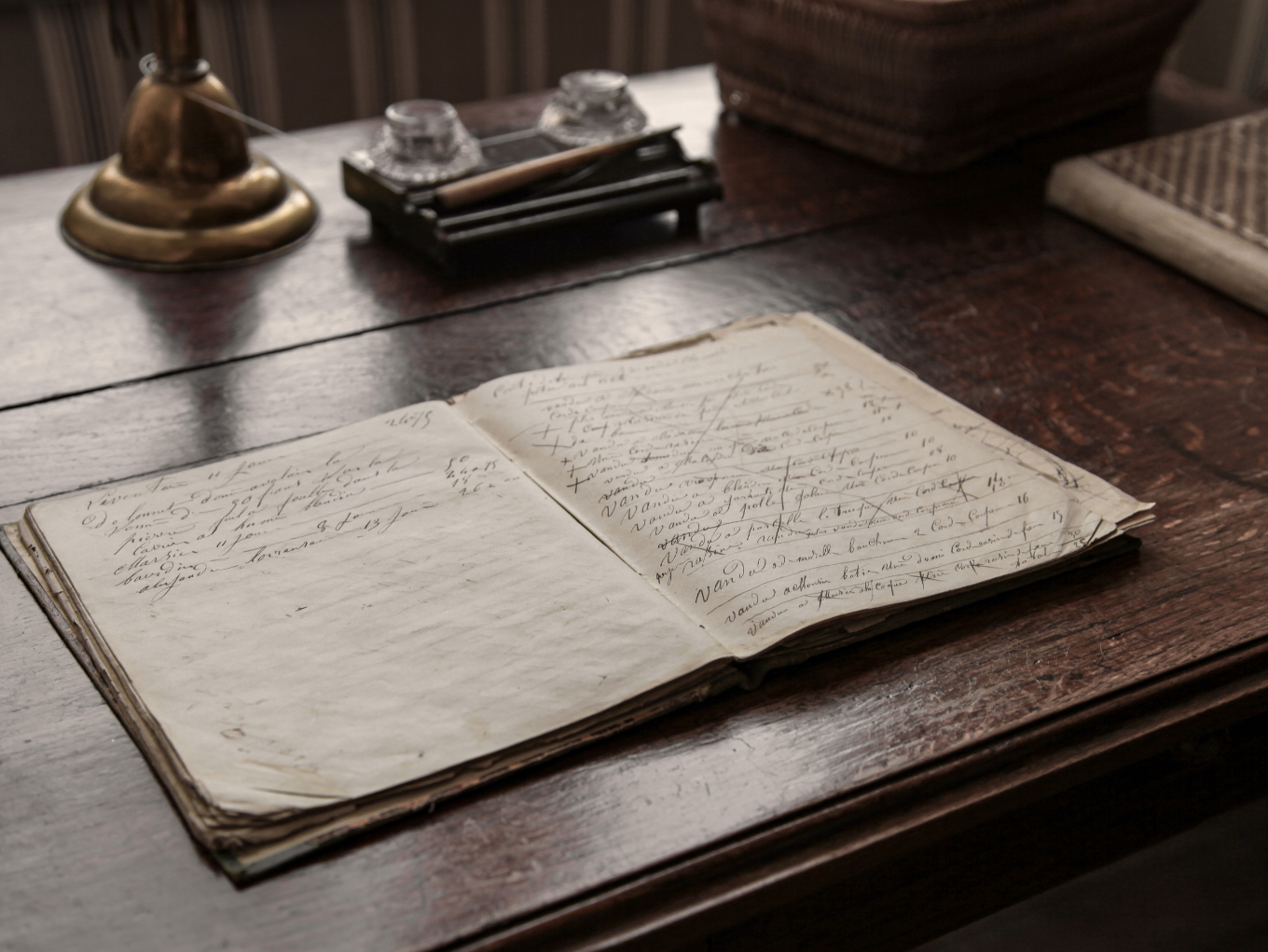

During your winter trip to London, you suggested that I take a house in Karachi and move there with my mother, at least during the harsh winter months. That glimpse into the past was becoming a four-year journey of the mind and I knew it was time to look back. I picked up the yellow notebook which you’d meant to give me at a London meeting. But then you escaped the lockdown and rushed back to your family in Karachi on one of the last available flights. I received it in the post, when the first lockdown was finally over. What an irony that I’m writing to you from the depths of another lockdown – I’ve ceased to count how many I’ve been through now…

But let me try to begin at the beginning. The story starts with a couple of calls between Karachi and London. You were sending me a book you’d published that I’d been asked to launch at a conference in Islamabad. The name of the book hardly matters any more: what does matter is that the best translations in it were yours. It was no surprise that the very year we met – you’re going to have to correct my dates, I’m trying to get the sequence of events in order, but I think I’m right – that very year, you began to write your own stories. And diffidently sent me one, and then another, to read. Visual artist, photographer, publisher, editor, and now you were a writer with a real spark. Across the distances, we’ve been writing, side by side, since then. But I’ve moved too far ahead and with your Virgoan sense of order, you might want a narrative line.

(Why do you keep a diary? My friend Maisam – the rubab-playing young man from Parachinar, who I met for the first time the day I met you – asked with a bemused expression on one of my trips to Islamabad. To keep track of time, I said. But why should dates matter? he said. Why this obsession with the calendar? My memories have no sequence, he wrote to me much later, but I recall scenes, pictures, feelings, sensations. Like dreaming, or watching a film, or listening to music. He remembers white peacocks in a garden that we saw from my hotel window, the full moon in an open market where he bought dates for me to take home, …. But he doesn’t remember when they happened or when we first met. But that flow of memory, I told him, is what I keep for my fiction. And now, without a diary, I’m faced with a dilemma.)

Let me start again. I met you in Islamabad in April 2017. No one introduced us, but we were waiting in the wings to begin our session. I don’t know how the subject arose, but one of us mentioned a book you’d published that I’d read some years ago. You said it was the first of a series of lost writings. Ours was friendship at first sight.

A few days later, you invited me to a Chinese dinner with one of your authors in Karachi, the city where you live and where I was born. I think you attended a reading I gave at one of the city’s popular venues from my new collection and you said you’d like to read it but I didn’t have one yet. You sent me a book you’d published of your grandmother and her sisters’ writings, and the manuscript of another lost novel.

I didn’t know that work would keep from me coming back to Karachi until the winter of that year. We met at the very same café: we had coffee with young writers. You had dashed in late to a reading I did a few evenings before, and bought a copy of my book, a tiny little book, illustrated with photographs – some of them my own – and paintings by friends.

It must have been in March of the next year that we met again. By then you’d decided you wanted a book from me. But a different one from the one you’d read. More stories, more images…. We talked about it over cortados, in a cool basement café, and looked at the plans you’d made of the collection of fictions I was going to give you. Yes, it was the spring of 2018. Karachi is beautiful in spring. Flowers, breeze, sea….

And you were in an equally beautiful London just a while later with cherry blossoms everywhere. It was April. I was taking my sister to Makkah and Madinah. When I came back, you were still here, you’d already been working on my book, we met in the café near the canal by me, you’d once visited this area often. In between, you’d written more and more stories of your own…we sat in the café and we talked about our writing and our lives.

Who, and what, are friends? As Goethe said, Elective affinities, or in another translation, families by choice? Later you would say: your real friends are here, in Karachi. But that comes afterwards. Sorry, I’m jumping ahead again.

I made it back to Pakistan that summer. I visited you at home for the first time and found you living in a house I had played in as a child. That is at the heart of another story I wrote. My book was done when we sat at your desk, made our choice of images – yours and mine – and arranged my writings in a sequence that combined fiction with biography and memoir. What does it matter? you said. Invention or truth, these are all stories. After work one day, we walked to the house where I grew up, just two or three blocks away from where you live, in the heat of a July afternoon. Was your book complete by then? Remind me? We went to the seaside where you took photographs of me, andI of you. My last moments of untroubled happiness.

I didn’t know that a fog of grief would descend on me when I returned. Betrayals. Deaths. A funeral. My book came out that September: time I felt I was walking through a dream. My return to Karachi in winter was consumed by collective mourning for my friend Fahmida in which I had to express my mourning in public.

By the time you came back to London in January, that month of flowers and swans, I had regained a measure of serenity. I promised to return to Karachi in April. You planned a celebration for my 64th birthday. We had no idea then that I’d spend that birthday on my back, lamed by a fall, and that only a few days later my heavy cast would be taken off and replaced by a hideous boot I wouldn’t be able to walk without for three months.

But I was determined to come home. During those months your sometimes relentless optimism made me write, even when at times I snapped at you in exasperation and asked you to be patient with my condition. You felt that work and flights of imagination were my best way out of my codeine-induced indolence and occasional despair when I doubted I’d ever walk again. In a way, you were right to push me, because by the end of that long convalescence and the period of recovery I had written several stories.

This morning I heard you speak, on video, about a story you wrote against the backdrop of the lockdown in Karachi. You spoke about the optimism, hope, and self-reliance that you wanted to convey in that story. You spoke again and again about silver linings and silver straws. And there are times during these multiple lockdowns – I couldn’t be in Pakistan, because I’d been placed in isolation, and anyway flight passages had been stopped – when I saw no silver linings, and even the very shortest straws had no glint of silver. I tend to confront grief directly, never to attempt an escape, until I wear myself out.

You were in conversation with Taha, who has, in turn, been my reader (and I his), my friend, my younger brother, and at times my surrogate son since that day that I got my new boot and he sent me a message of good luck while I waited, in a wheelchair, for what seemed like hours for an ambulance to take me home. I’d just read his first novel on my Kindle. I didn’t even imagine then that he’d be waiting at the airport when I finally made it back to Karachi that September to start work with you on the book that you’d inspired me to complete, almost extracted from me – the fulfilment of a dream, to write in my mother tongue. You contributed exquisite translations of some of my tales. I felt I had known Taha for ever. I would divide my time, in café and on drives or in the patio of my club, between the two of you on those mild, late summer days and evenings. Somehow, I couldn’t ever make your timings coincide, though Taha once drove me to your house, and his driver lost his way.

And then – almost by chance – the three of us were together in Islamabad later that month, and on the plane back to Karachi you had your first real conversation. I came back to London and wrote, in one day, a story which you decided would be the title story of my Urdu collection. You’d also started writing stories in Urdu, one after the other, and a new surge of imagination and perception carried you onwards, outwards.

Back in Karachi in December 2019, I looked with you at the beautiful designs you’d made for the cover of my book. But by then – I’m using that phrase a lot – I had been told my body was harbouring a hidden adversary. The title of my book, Zindagi se pehle (Before Life – the word maut, death, was excluded) had become a premonition of the period I was about to enter with the death of my sister at the start of the new year and the confirmed diagnosis of my cancer.

I really don’t know how I made it to Karachi in January. But I did, to honour a teaching commitment and mainly to launch this book, and to search for a new life after death. I was sick much of the time. You couldn’t make it to that launch; you’d left that morning for a wedding in America. It seemed that some bell of warning of the pandemic had begun to toll.

I have one happy memory of that trip, perhaps the only one. You were sitting between Taha and me, reading aloud from one of my stories: he’d asked you up to the platform on which he was interviewing me. We sold the first, fresh copies of the Urdu book we’d worked so hard to complete in time for a festival. We three dined together on South Indian delicacies later. (I didn’t know – again, I seem to be saying this a lot – that I wouldn’t see Taha for the rest of that year. Because of lockdown circumstances, another friend took his place at my side on my next trip. I don’t know now whether I ever will see him again. But his presence in my life is constant.)

Once more I planned to be back in spring, but first we entered lockdown, and then my mother, engulfed by the grief of her youngest child’s death, died too. We’d tried hard to save her but in the last days of her life she felt her dead were calling her and she said her farewell to me. It was just a week after my April birthday: she had encouraged me to spend it in Pakistan. In the weeks that followed I’d sit alone for days and sing loudly to the white walls when the dark wouldn’t fall to embrace me. But there are other moments to recall. The hundred photographs you took, starting with objects glimpsed or partly glimpsed in dark spaces, and then, as Karachi gardens filled up with flowers, you moved into your garden and began to photograph birds. (You told me to try to do the same. I couldn’t. I was tired of trudging the same streets and photographing the same gardens, day after day.) A photograph of a koel inspired you to write a beautiful story. The arrival of the manuscript of your first book of stories, which you will publish this year. Friends at home and abroad would send me music and songs to console me. Mimi would call from her home that was once a bus journey away and now felt like another country. Friends sent me photographs from their farmlands in Sindh and their gardens in Rome. Maisam played passages on his rubab, sang to me in Pashto, Farsi and Urdu, sent photographs of the plants he was tending, and of spring in Parachinar.

When we were allowed to escape our prisons, Ruth was the first to come and walk with me to the garden not far from where I live. It was in full bloom. We sat on a bench with the required distance between us; we read each other our favourite poems and passages of our own work. I was inspired to write a short fiction – my first in months – and sent it to Taha, for the anthology in which you, too, had a story. Then things began to improve here. My friends came to visit when the café by the canal slid off glass ceilings and flung open glass doors: we could eat and drink and laugh when the evenings seemed to go on for ever and the waters of the canal glinted in the distance. Waheed came, and Francesca. My niece married, and then my nephew.

I realised then that I hadn’t kept a diary in at least two years. What happened in which month? Did I walk to the path on a Sunday in late June, or a Saturday in July? When did I fall off a chair and injure my ribs? I can’t remember. That, then, was the test: was I writing fiction or an account of my own life? When the yellow notebook arrived – was it in June? I began to put down thoughts for this autobiographical work you’d urged me to complete in October. (Last week, on the phone, you reminded me, when I told you I was done, that I’d said I needed until the new year to gather my scattered memories and reflections. Many of them aren’t here. Too deep a pond and I can’t swim, or too steep to climb with my lame leg.)

All my life, I’d believed the book of life was interleaved, like those bilingual editions which carry different facing pages – happy moments on one side, perhaps on a gilt-edged page, and sorrows on the other, edged in black. I came to another conclusion over the weeks spent in quarantine (the price I paid for coming back to Pakistan in September when I did make it back). And in the three months of so-called shielding. These are two separate books. The dark, open book of grief, and the yellow notebook of happiness in which too many pages are blank because you’ve just been too busy living to write them down and when you search them, they just aren’t there, like those photographs of the two of us by the seaside neither of us could find this morning.

The dark book was open again when I came back from Pakistan and spent twelve days trapped in a third floor apartment with no permission to leave. Then the doors opened again. Mimi crossed the city to see me after nearly nine months: she said, visiting Little Venice is like a trip to another town. A day later, doors began to shut upon us all again. I met Waheed in an open courtyard at sunset. Let’s go to Iran when this is over, he said, us two, brothers. I began to dream of Shiraz and Isfahan.

I sat with my niece Leia one autumn afternoon and told her how we turn life into stories. A few days before that, I’d been to the little garden with my nephew and found a tree laden with red berries which I’d picked and eaten. They tasted like lychees and summer. A few days later, I walked with her to the same garden to meet her brother and his daughter. The grass was red with fallen berries. I saw a crow and wanted to photograph it for you. But the crow hopped away and I could only photograph its back from a distance. So in a memoir, I said, I’d try meticulously to preserve the sequence of events, but in a fiction I’d combine the two moments into one early autumn seamless idyll.

As winter came, I would spend weekend afternoons in Leia’s sitting room with her children playing around me. She’d be at her piano, her fingers gliding over notes from Chopin and Satie that pierced my entrails. She set a poem I wrote to music. I felt that as long as I had these little joys, nothing else would matter. We hardly noticed autumn turning into winter. We would laugh like maniacs about remembered incidents. And she would sometimes place a gentle hand on my arm when we thought about our lost ones.

And then at Christmas I was told I could no longer risk spending time with children. The doors between us shut. I can’t even bear to talk about that separation.

Is it easier to mourn the dead, or miss the living? Distances are strange. You are in Karachi, but we speak regularly. My niece is two doors away, and I can’t see her. Is it the hope that we will see our loved ones again on this earth that keeps us going?

I have said my farewells to friends in Pakistan because I don’t know when, if ever, I’ll be permitted to travel again. You said this morning on the phone that you are guided by a blind faith in providence that will bring me home. I will leave you with this hope and optimism and with this letter that is so long. I had hoped to follow some kind of sequence but perhaps I have only recalled the past as a dream with no dates.

I remember the long conversation I had with you about our lives and our hopes and our writing as the sun set in Karachi the day before I left. I hoped to return in December. (That trip was cancelled.) There are photos I took of you, edged in the evening light, serene and trying not to smile. I often look at them to recall that day. And those of me, that you took when I was unaware, show a me that has rarely been captured, in what might be the winter of my life.

Your friend

Aamer

January 2021