I met writer, publisher, and Dalit activist Yogesh Maitreya, in his home city Nagpur over a cup of coffee and we had a freewheeling discussion about various subjects, but specially his role as a publisher and writer. Yogesh’s publishing house Panther’s Paw specialises in publishing Dalit writing, and is the only such publishing house in the country. Panther’s Paw has published poetry, essays, translations, and short stories from various Dalit writers including B. R Ambedkar. Penguin Random House recently commissioned Maitreya’s memoir, titled- Water in a Broken Pot

Meeting Yogesh one is struck not only by his candid replies, but also by his sense of articulation, and his informed reading. Here is a man not only with a vision but also a certain fearlessness about him. Over the course of this interview Yogesh tells me that he does not edit any of his writer’s books, because he wants the raw tonality of their stories preserved. In presenting this interview, we do the same. No part of this interview has been edited. Sometimes Yogesh cuts across different subjects, and at times he goes back to it. We hope our readers will find the same sensitivity and power in his voice, that I as an interviewer did.

On being asked about Indian English publishing

The problem with Indian English literature from India is basically that it is a product of a certain class. English had so far (till the advent of social media) been a language of a certain class. And that class also had a particular caste in that. So English was mostly a Brahmin affair.

If you do a study of the kind of literature that is available, or coming out of India before and post social media, you will find drastic variations. Nowadays, even the upper caste people are talking about caste disparities. Say for example someone like Tharoor, who despite being a diplomat, never really engaged with caste problems, neither did he write about it. He is someone who claimed to know much about the history of India, but never bothered to mention or write about Ambedkar, as a part of modern Indian history.

But with the advent of social media, we have been given a window, where you can write whatever you feel like writing without censorship. Earlier publishers were not interested in literature that talked about caste. This is also, because they did not see any market for such literature. For example, a mainstream publisher will publish anything, whether it is from any kind of writer. But these publishers did not really see the caste discourse as having any market. Post social media, people from the universities belonging to the Dalit Bahujan community, started sharing about their lives. In India, because of our big population, anything can be converted into a market. So when people start consuming literature about caste, and writing about the problems of caste, or talk about the writings of Ambedkar, it becomes a market on its own.

For example, a book like Hatred in the Belly brought together so many writers who talked about such things. And the book is still selling. After the popularity of this book, I started understanding that there is a need for such kind of literature, and hence Panther’s Paw Publishing. It dawned on me that we needed more publishers from our community who could fill the gap, and publish such stories by underprivileged castes in the English language. Each book takes couple of months, and there are so many stories that need to be told.

On being asked about editorial process of book publishing from Panther’s Paw-

I wanted to break away from stereotypical frameworks that have been applied to publishing in Indian English writing in India. I do not tell my writers anything about changing their writing, about how they should write or how much they should write. We only do copy edits, we let people experience the words the way it was written, in the very flow that the writer wanted it to be. We make sure that each book has a nice representation in terms of cover, and the quality of the pages, etc. I made sure of this, because in Maharashtrian language publishing, I saw that the methods were still very traditional. They did not use very good paper, even the cover works they do are very different from how we do it. Incidentally, we get a lot of comments about our covers, about how unconventional and unusual they are. Most of our recent covers have been done by Shiva Nalla Perumal. We do not put the writer’s name on the top of the book, this is something that traditional publishers will never do. All our books have different content, and the idea for the cover also comes through that route too.

We want to normalise the way a Dalit Bahujan writer writes. We do not want edits in that. Whenever a writer writes from an anti-caste perspective, irrespective of the content- his life is one which is not present in the literary imagination. In most such cases, that person would be a first-generation learner. And from the point of being a learner, to reading in a language, and to also aspire to write in that language, while going to the extent of producing something in the vocabulary that he has learnt, is a very big leap for him. You see, we do not have a reading habit in our homes, because our parents were so involved in the survival struggle. You can imagine this yourself. In the normal process of things, you need time to go buy a book, to read and reflect upon it. How that time is created in your life, is a privilege. Because when you spend three days in a week reading a book, it means, that you are not working for those three days.

But for people like my parents, or their generation, they had to be there in the fields, or working on the road, in the factories- because if they miss out on even one or two days of work, it will have repercussions. This of course also has a lot to do with how formal and informal sectors work in India.

On translation–

So far I have translated one political history book, which is called the Ambedkarite Movement, after Ambedkar. It is about the history of the Dalit movement in Maharashtra after Ambedkar’s renunciation to Buddhism. There are two more poetry collections that I have translated. After the pandemic I was busy with book distribution and the process of publishing books, and I found it difficult to find time for translation. Now we are commissioning translations too.

Translations have been doing better sales. Original work in Marathi was hardly being bought. One good thing that is happening is that the content that we are producing in English, that is being translated into other languages like Kannada or Tamil. I see that as a success in terms of more people engaging with the content that we are creating in the area of anti-caste movement. The more people write, the more others read us. And then there are others who read or borrow second hand books, even that is a success for us.

I go through social media, or use my own network, etc to publicise the work. People directly reach out to me when they hear about the books we publish. This is also about living the anti-caste way of life. If someone wants to buys such a book, then they should be able to buy it directly from me. Do not buy it from a third party, who probably has a caste network, and because of that network, they are going to mint money. So, the books should be bought from me, because not only am I the content creator, but selling these books is also part of the movement we are part of. Antonio Francesco Gramsci also says the same thing, about the practice of philosophy. Hence, I must practice what I say. Tomorrow if a student tells me that they do not have the money to buy the book, I might give you the book for free, because I’m the publisher.

For me, this is about remaining free. Tomorrow I might produce two hundred books, and I might want to take off for three days, I want to be able to do that too. I see that my generation has been working like donkeys, but then that is also the story of my parents. My mother worked as a house maid for two decades, and now she does the same thing at home. Even if I tell her that now you do not need to work like this, and that she should rest, she tells me that she feels sick when she takes rest. That is how they were internalised.

The ideas about resting, about having some time for yourself, about creating art, or relishing it. This is also about how you understand Marxism in your life, how you understand Ambedkarism in your life.

On being asked about people transcending the class barrier vis-a vis the caste barrier-

Class is in principle a movable position. In the US, someone from the street might one day become a billionaire. In India, if you have a low caste, that follows you, no matter which class barrier you cross. A Dalit guy will still be called a Dalit, even if he has a car or goes to a pricey hotel. He will still be seen as a lower caste person.

A brahman, even if he is uneducated, does not compare to a Dalit. Irrespective of how powerful a Dalit becomes whether he is collector or an IAS officer, because his caste is something that he has internalised as a part of his growing up days, he still feels it. So even when our President today, goes for some official function and the photographs are seen, we know how it is presented we are smart enough to gauge that. The same thing is true of publishing, they are not immune to that. What I am trying to do, is make people see what is unnatural as just that. What is abnormal should be seen as abnormal. So, that is what we are saying, that caste is abnormal, it is unnatural. We tell people that caste has also made you a victim, because you have lost your sensibilities, in how you behave with people. And it is very apparent, across cities, on the roads, everywhere.

Economics and caste are related because as a Dalit even if you get a govt job, but are assertive about your caste reality, you are in the radar of the upper caste, and you will be vindicated, and tortured in very cold-blooded ways.The scenario in such govt places is so nasty that no one would like to work there, but most of them stick on, because it is some kind of sustainability after many generations of being mistreated.

In a way I am relieved, as someone who is in the field of literature as a part of the anti-caste movement, we have a market & we do not need anything extra, we already have a market. We are going to be a very huge market and that is why bigger publishers are also interested now in our stories.

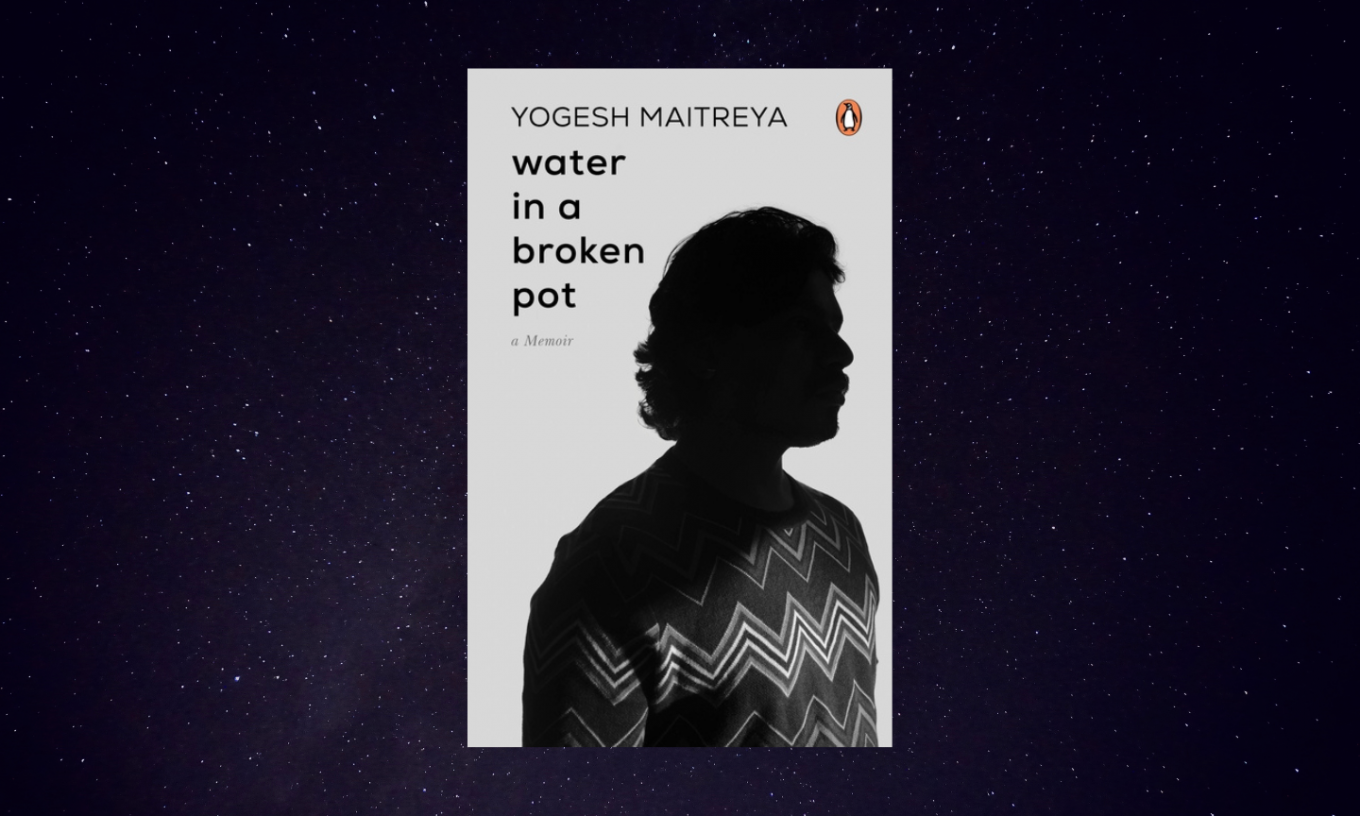

In the same vein Penguin reached out to me to collaborate with me for writing my memoir. I agreed because, I want more people to hear my stories. My roles are different as a writer and publisher too. My book, titled Water in a Broken Pot is just out. As a writer I write only what I want. As a writer my sensibilities have been shaped so much by caste that it is difficult for me to write about anything else without looking at it though the of caste angle.

I do not have the privilege of unseeing caste. Caste is everywhere and everyone’s life is a product of the material dialectics of the caste equations that are ever present in India. Other people can not talk about caste and still flourish, but for me, someone who is born into caste, and its deprivation, it is inevitable to talk about it.

On being asked about the future of Panther’s Paw and whether it will remain a niche publishing house-

I believe that Panther’s Paw is a mainstream publishing house because numerically speaking Brahmans are the minority, we are the majority. We are far more than they are, so how can we be a niche publishing? Historically speaking, Dalits lacked the means for production. But that is no longer the situation. People forget that we are the majority. For our first book, I sold 300-400 copies, I did not have to do any marketing. I just have to put up something, and people themselves buy. People reach out to me themselves.

In the future we want to translate the stories of oppressed communities around the world, we are already in such talks with others. We are also a community who is learning, we want to publish more translations, so we are in the process of buying rights, etc.

People outside India have been reading our books. Some of the content from our books are being referred to in academic papers or been part of class room discussions. It happened in Cambridge University, and a few other universities in the UK. And all of this has happened organically, because people realise that it is important, which is why people are creating a discourse around such works. Also, I think this is one of the more creative ways of talking about anti-caste movement. It need not always be about taking out morchas(staging protests). This is my way of doing the anti -caste movement.

One being asked whether his parents and those in his community understand his fight, and how others from the community can continue the fight in his absence-

My father was a driver and my mother a house maid, they do not understand what a publisher does. They know that I do something with books, that’s it. My friends who are into reading, they find this journey important because of the content. Many different caste people have also engaged with us since last couple of years. They have been friends to the publication and to me. That is an achievement, because we need to engage across society as far as caste matters are concerned.

We need to have the common understanding that while there might be differences, but we will not hide them. Hiding who we are from others, is going to further our ignorance. My parent’s life never allowed them to come together with their friends and share about their lives. Even if it is just sharing a meal, or their thoughts.

As far as the journey of anti-caste movement goes, I am just one of the wheels of this movement, in the field of literature. In this changing context, sharing my stories and telling different kind of stories without stereotypes, is what needs to be done and this is only possible when different kinds of people come in. Our content is very rich and very layered. The more I meet people from different parts of the country, I see that their ideas about beauty, love, cinema, literature etc. are very different from each other. As a publisher I want to publish all these variations too. This is an organic and decentralised movement in that sense. In the future, there will be other people who will come in, who will also publish other stories to take this journey forward. And because of this, the movement is unburdened, and that is what I call remaining free. As of now Panther’s Paw is a sustainable venture. When we had begun, we had the fear about how to publish our next book. But despite the challenges, we continued to publish books, people have recognised the efforts and realised that there is a persistent effort that has gone into this endeavour. As a result, we now have a bigger readership too.