Title: A Bite in Time – Cooking with Memories

Author: Tanya Mendonsa

Publisher: Paper Project (an imprint of Design Foundry)

Year of Publication: 2022

Tasting with Memories

As a child, I remember waiting for the familiar honking of the bulb horn and the booming voice of the biscuit wala. Sound heralded aroma – of freshly baked bread, cream rolls, khari, veg puffs, biscuits, the ubiquitous ‘rusk’ to dip into tea or milk – a world of sensory delights mixed with the anticipation of tasting them. The owner of the voice parked his cycle at the edge of the main road between our house and the hospital. Tall, his beard lush, eyes dark, crinkled with the familiar ready smile, he would open the various bags and boxes laden with these goodies. Waiting for him meant waiting for all of these, a world in itself, made up of these components, inseparable from the excitement of gathering around his cycle. The memory evokes an age that has passed, a way of life that perhaps exists only in some corners and pockets of the country, but the voice, tastes, and flavors are fresh in the mind and on the palate.

Tanya Mendonsa’s A Bite in Time: Cooking with Memories, her second memoir, evokes such a world of remembering, cooking, tasting, celebrating with friends and family. The book turns into a table, the readers vicariously partaking of the food, across different countries and cities, different times, with different people. This book is thus, not only about recipes and memories, flavors and aromas, but also a canvas that evokes the easy cosmopolitanism of an age, the seamless blending of customs, traditions, innovations, of peoples and cultures in places such as Calcutta, Paris, Bordeaux, the French countryside, Goa, Rome, Perugia and Trieste, Bangalore, and finally, the Nilgiris.

In the preface to her popular cookbook Home Cooking, the American novelist, essayist and cookbook writer Laurie Colwin writes: “Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers.”

Tanya Mendonsa begins her memoir with a poem, a tribute – ‘My Mother’s Dining Tables’. It celebrates a cliché: a mother’s love through her food. But it is unapologetic about the cliché, using it to trace her own journey through life, returning over and over again, despite the many kitchens that are present in the book, to that of her mother. It conjures a sense of family and of warmth, sometimes present, sometimes lost and yearned-for, the sense of homecoming.

Mendonsa sets up a style that runs like a spine through the book: she creates a slice of life that leads to remembering a particular dish, then she follows up with its recipe. This structure heralds the dish through first its flavors and taste, and then, once we have begun to think about the dish, we are given the recipe. Sample this, for instance:

At the end of the recipe for roast chicken and its gravy, she says, it goes well served with lemon rice, which my schoolfriend, the writer Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, taught me when we were ‘grown up’.

It was at Chitra’s house that I first ate the quintessential Bengali meal – her family lived in the traditional way, and her mother, who was very religious, cooked and ate her food apart from the rest of the family. First we washed our hands at a little brass tap in the garden courtyard, and then we went to my friend’s little red floored bedroom, which looked out onto the cool garden and climbed onto her bed, which was covered by a spotless white sheet and white bolsters to lean against. We were brought our lunch on brass plates by the young maid, who giggled at our solemnity.

“Each plate had a couple of spoonfuls of fresh green spinach, oozing a little oil, beside a little mound of fragrant basmati rice with a knob of ghee, a handful of perfectly fried, golden potatoes, a little pile of salt and a wedge of lemon. On a separate plate were some slices of river fish cooked in mustard oil, still sizzling, and on another, tender little ears of corn. I still remember all the separate tastes and colours of that meal! (pg 34)

The atmospherics, mood, setting, the sensory details, and then, on the same page, we finally get the recipe of what started off this narrative: Chitra’s lemon rice. This approach seems to ‘poach’ the dish in an emotion, a setting, a memory, turning each dish into its own narrative, simmering with its own characters.

For example, the memory of eating from your house help’s plate as a child, sometimes surreptitiously, hiding from family members, the shared joy both a secret and a pact between the two of you.

My brother Michael… and I had an Ayah from Goa called Jaquine. She only spoke Konkani… so that’s what I learned to speak to her in. What I remember most vividly is sitting cross-legged next to her in a corner of the verandah, and being surreptitiously fed bits of her lunch, which was the traditional Goan fish curry and red rice. Jaquine would roll tight little balls of rice and curry and pop them into my mouth. I have never forgotten that taste. (pg 12)

The recipe for traditional fish curry follows soon after.

These narratives of lives and the food that so naturally associates with them give us the picture of an age, like all good memoirs do. However, although the recipes are about the author’s life, a life well-lived, well-traveled, about the many friends and acquaintances with whom she shares her journey of food, tasting, cooking, making mistakes, learning, it is essentially a daughter looking back, constantly, tracing backgrounds, locating histories, returning over and over again to the food her mother served.

In Chapter 5, we read the recipe of chicken (or mutton) stew – homely, familiar comfort food. However, it takes its resonances from the comfort and refuge that it provides to a clutch of women from a working women’s hostel run by terrifying Spanish nuns who starved them all and hung bloodthirsty pictures of saints being tortured over their beds. Once they discovered our house, they were running in and out of it all the time, diving into the kitchen to devour leftovers…. They especially loved my mother’s stew, which is the perfect comfort food, together with that nursery favourite, bread and butter pudding. She enlivened this stew by using whole black peppercorns, and if she had some spare pork or bacon at hand, would throw in a few pieces for added flavour…. (pg 47)

As we turn from the years spent in Calcutta, we leave behind a way of life, of the 60’s and 70’s – a gracious, hospitable, cosmopolitan, inclusive India that embraced strangers at the table. The kind of life where the flutter of a falling leaf was sensed as acutely as the changing seasons and their shifting light and warmth, a time of standing and staring that we have ceased to enjoy. This cornucopia of tropical sensory recall segues into the author’s Paris years, but not before we have a delectable description of eating out in Calcutta, with its kaati kebabs, parathas, Bengali wedding feasts served on banana leaves, rice puddings and Bengal’s sweet curds, which can never be reproduced outside of Bengal, like the crème fraîche one gets only in France (pg 52).

The Paris section fills up with the smells, tastes, and textures of French cuisine, liquid as its wines, creamy as the many cheeses on the various tables she eats at, vibrant and subtle in turns like the paintings and places she describes. Paris is full-bodied, the descriptions reflecting the author’s engagement with the place as an adult, looking at it from a perspective not shaped by others, but with the immersion of first experiences.

Sometimes, living in France was like living inside some of the Impressionist paintings I had seen in books and now saw in museums. One Sunday, Patrick, a friend of his and I simply drove north out of Paris, along the river. It was late spring, and the leaves were a mist of young green on the plane trees bordering the roads, with weeping willows bending down to the water and catkins nodding from the birch and oak trees. The sun was warm and the earth smelt fresh and clean after the city had been left far behind. This was Monet country, where he had lived and painted by the river, often joined by Manet, who lived nearby, and Renoir. (pg 70)

Through the years in France, she turns again and again to her mother for recipes, but it is only after her return to India after 20 years that she slowly turns to cooking, primarily baking, for her dog Joshua. The recipes in this book are thus presented through the patina of time, remembrance and research, and structured in numbered chapters that follow a linear journey – from childhood and the growing up years in Calcutta, to France, to Goa, and finally, to settle down in the Nilgiris, in a remote area 6000 feet up, full of wild animals,with her partner, the painter Antonio E. Costa, and their dog Joshua.

Recipes are accompanied by tidbits of information regarding alternatives to various ingredients, processes and possibilities. So, for example, at the end of a recipe for pork vindaloo, that quintessential Goan dish, we have an asterisk whispering to us: *This dish profits from being kept overnight and re-heated to serve. Or, at the end of French Shortcrust Quiche: *If you wish to be adventurous, you can also add two large onions (sliced and then caramelized with a teaspoon of balsamic vinegar and one of brown sugar) after the bacon to the filling. The tone is of an aside in a kitchen, a quickly shared secret.

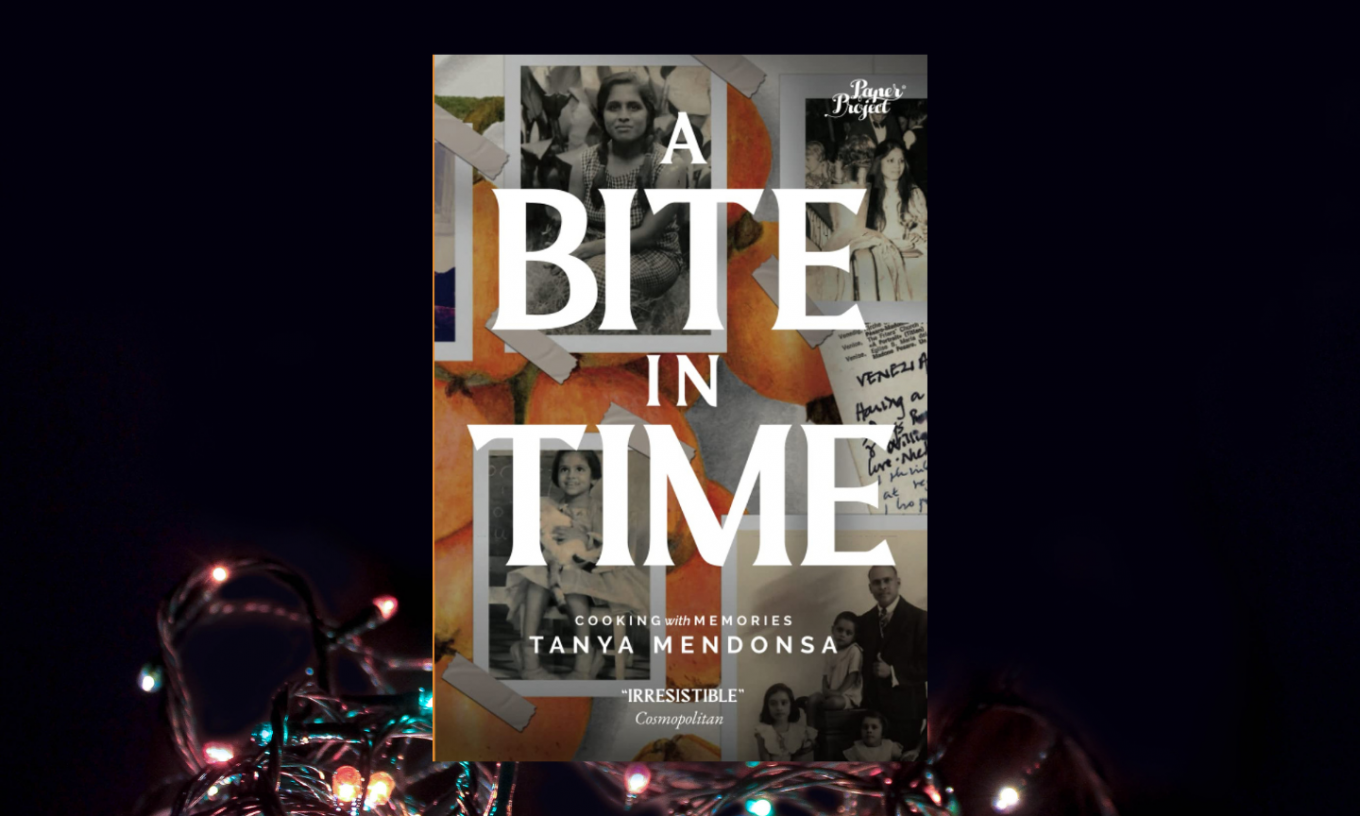

A scattering of old photographs and smart black and white drawings by Mukund Venkatraman add to the sepia-toned elegance of the book, enhance the sense of tribute to Gilda Mendonsa, to her cooking as well as the cookbooks she wrote, but in a book that celebrates cooking with memories, there are no photographs of food. Books about cooking are usually a delight for their visual offerings as much as they are for the olfactory and the gustatory. Here, one sorely misses the visual accompaniment.

When I ask my postgraduate students – across the years – to think of sensory memories, it is usually the remembered smell of food to which they respond. Memory and food inherently accompany each other, the sense of nostalgia around it different from the other senses. The other ‘memorable’ smell, I notice again and again, until I ban it in the class for fear of losing out on other memories, is the fragrance of their mothers’ perfume. And so, we return to the basic ingredients of this book: mother and food. Gilda Mendonsa cooking for her children slowly gives way, by the last pages, to Tanya Mendonsa cooking for Joshua. Thus, the tradition continues – mothers, love and food… along with the food cooked by so many others who fill up her life.