“Memories of the events persisted, like insects around a glob of

sugarcane, crawling into every crevice of the mind, filling him

with their black fragrance.”

Chigozie Obioma’s An Orchestra of Minorities

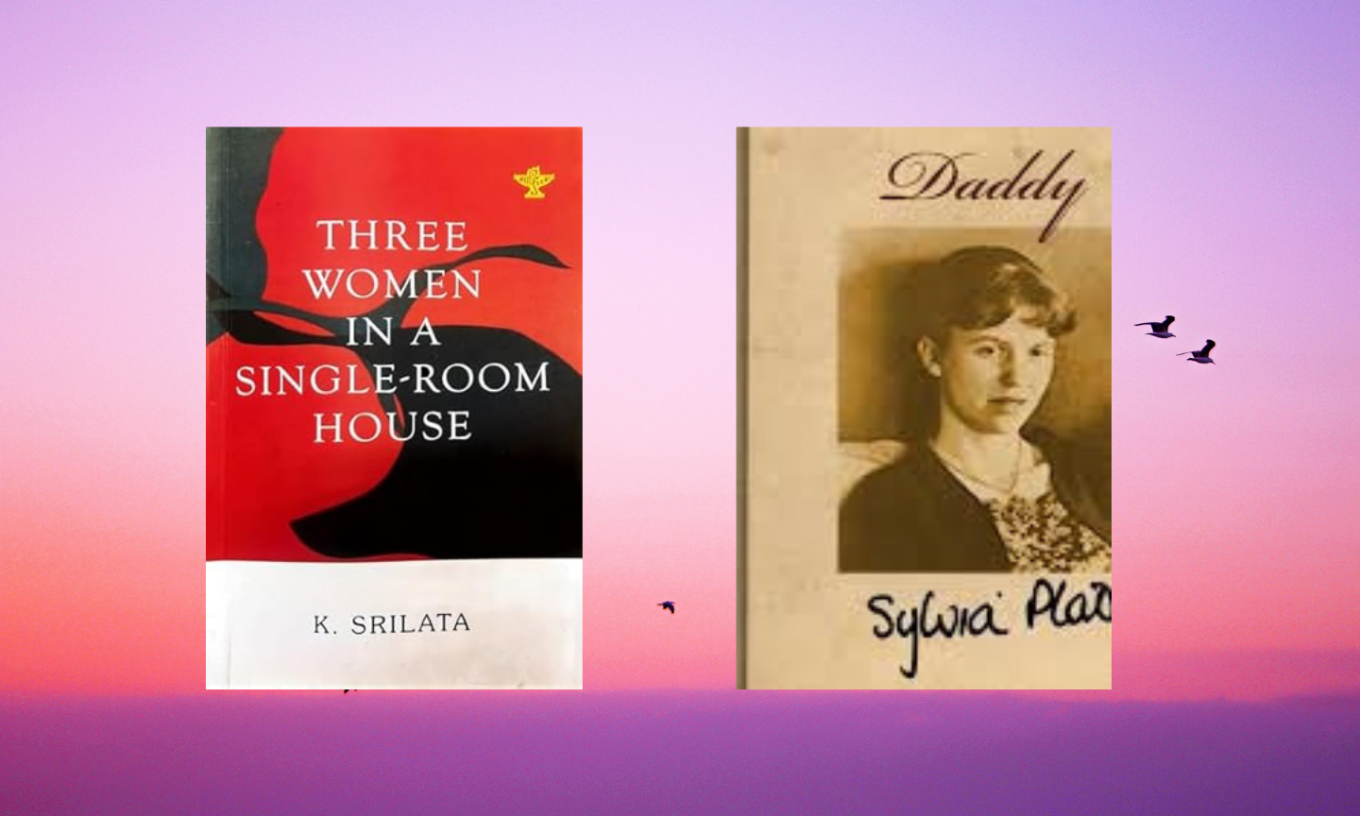

I could not help reading K.Srilata’s recent collection of poems ‘Three Women in a Single-room House’ (Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 2023) in conjunction with Sylvia Plath. To be precise, reading Srilata’s poem Father and Sylvia’s poem Daddy is to analyse how the nature of knowing is contingent on personal and cultural memories. Both the poets script their father-oriented poems with the syntax of confession, wishful thinking, and self-awareness. Their tenuous belief in the redemptive presence of a father figure is forged in the crucible of their fervent longing. This hope against hope provokes the frontiers of knowing unravelling the ‘unknown’ and ‘absent’ father deeply etched in the psyche of the poet-persona. The nature of absence becomes for both the poets an existential imperative to seek the estranged father in the privacy of their interiority. In both the poets, memory at times becomes the poet-persona’s hedge against falling under the spell of delusion of the absent father’s presence. The memory, involved in both, inhabits a fatherless world that entails a politics of deprivation, discord, and domination underwritten by traumatised claims of apathy.

Both Srilata and Sylvia manifest a unitive urge; however, it is appallingly ghastly in Sylvia as she embraces self-destruction. It is singularly transformative in Srilata as the act of denial is translated into an act of personal archive in the form of poetry. Unlike the daughter in Srilata who is bent on exploring the possibility of a recovery and discovering the act of writing, Sylvia’s persona is unable to fight against her psychic enslavement to self-hate leading to her suicide. The father is ‘unknowable’ in both as they are burdened with the tyranny of their fantasies. In both, the father is symbolic of male hegemony and its implacable identity creates contending dualities: hope and despair in both Sylvia and Srilata. This ‘absence’ of the father figure is rooted in the artistic psyche of both the poets. In Sylvia, it is with ominous associations of death while in Srilata, it is with the enduring value of the single-minded devotion to the Muse.

In their search for the father figure, both Srilata and Sylvia manifest a process of emotional catharsis. They retreat into a rhetoric of idealistic aspiration where the elusive nature of reality that the father will never come back is deferred. This sense of deferral becomes poignant as the fervent longing for fatherly love burns brighter. Unlike Sylvia Plath’s Daddy, Srilata’s Father is not authoritarian. He is not savagely irreverent in pushing Sylvia to the threshold of outrage as the menace of memory stabs into her psyche: ‘Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.’(Daddy) In the struggle between a narrow contingency of selfhood and a wide appreciation of selfhood, Sylvia’s persona is a defeatist where her irreparable grief gets the better of her and she is unable to find her personal identity behind the façade of a father figure. Consequently, she succumbs to the nihilism of her psychic anguish. The daughter in Srilata overcomes the anxieties of fatherless love to score a personal triumph, thanks to her mother, the Tamil writer Vatsala. Without her indomitable spirit of resilience, Srilata would not have nurtured an abiding love of the external world to discover the redemptive power of absence tellingly displayed in her world of poetry. Srilata’s collection of poems The Unmistakable Presence of Absent Humans(Paperwall 2018) comes to mind. Conversely, Sylvia is star-crossed as she submits to her tragic fate with a sense of intense resignation: ‘We have come so far, it is over’ (Edge)

The poem ‘Father’ by Srilata is a poignant evocation of a world of make-believe where the daughter ventures into her surreal world of meeting her estranged father. Her dream world, ironically, is scarred by streaks of deception the gullible daughter fails or refuses to note the fear of letting her dream world slip away. The poem ends on a plaintive cry against the threatening crudity insinuating that the father is romantically adventurous as the daughter assumes with a brutal brevity of bitterness: ‘I see her, a woman about my age,/walk towards him, take his arm’. Sadly, the daughter melts back into her memory as her urgings are unheeded. Her dream wears a parched look. The father-starved daughter is left stranded in the rain to discover the mystifying phenomenon called ‘father’. The rain conjures up the hostile image of a tyrannical, godless world of hope. Amidst the haunting note of pathos, the ending of the poem with the ‘umbrella’ metaphor is tinged with a tragic aura of hopelessness that summons the daughter’s sceptic self to unveil the deception of the so-called dutiful father figure. The metaphor of ‘umbrella’ is a refuge from the fear of the stark reality of father’s infidelity and an escape into the world of innocence and naivety. The intensity of rain evoked in the poem drifts the poet persona to the brink of despair and anguish.

Both Srilata and Sylvia seek to mirror the tangibility of their respective vision of an absent father figure. They attempt to strike roots in the barren landscape of fatherly love as unrequited desire for union gnaws at the hearts of the personas. As I read them together, I recall the opening sentence of Vladimir Nobakov’s autobiography Speak, Memory : ‘The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.’ Unlike Sylvia, Srilata’s alienated, father-craving self is able to break through the agonising paradox of absence and presence in invoking a fatherly figure.

Both Srilata and Sylvia unearth the past with their unalloyed commitment to words. They invoke the lost words in the same fashion as Margaret Atwood would like us to believe in her poem ‘Notes from Various Pasts’ – ‘ lie washed ashore /on the margins, mangled/by the journey upwards to the blue grey/surface, the transition’. The transition is an act of self-discovery. Unlike Srilata, Sylvia treats herself with tyrannical stringency feeling gravely wounded and lacerated recalling the embittered and scarred personal memories. Moreover, unlike Srilata, Sylvia submits to the paralysing obsession with her narcissistic self. Both Srilata’s poem Father and Sylvia’s poem Daddy broaden the interpretative frameworks of discerning readers. To borrow words from Jean-Francois Lyotard, Sylvia’s persona is oriented towards the ‘accomplishment of vengeance’ while Srilata’s persona is geared towards the ‘preservation of memory against forgetfulness’.

Both Srilata and Sylvia, where absence freezes into eternity, underpin the inevitability of absence, the absence of a father figure. To study Sylvia and Srilata together is to textualise the discourses of absences, exemplify the intertextual nature of their works, the language of subversion, and the richer plurality of multicultural reading. In retrospect, a parallel reading of both these poets recalls the illuminating lines of Vikram Seth’s novel-in-verse The Golden Gate that impart a ritual grace of tragic sensibility: ‘John, pay what are your own heart’s arrears. /Now clear your throat, and dry these tears.’