Asperogers

My uncle Khurshed, younger brother of four sisters of whom my mother was the eldest, worked in Bombay as an engineer, and now that he was earning his own living and could even send a small amount home each month to supplement his father’s pension, declared that he wanted to get married. He wasn’t asking for the traditional search for a suitable girl to be initiated, he said, he had already found the girl he wanted to marry and insisted that he was deeply in love with her.

I was about eight years old at the time and my mother’s family—her mother had died a few months before—lived in Poona. A family conference was called that evening as my uncle, in his late twenties or early thirties, was impatient to seal the deal and get the families together. He looked upon the conferences and examinations as a formality.

My grandfather, who always stood a bit aloof from matters of birth, marriage, death and most other things, entrusted the talks and possible arrangement to my mother Shireen, his eldest whom he regarded, after the death of his wife, as the senior lady of the family.

The four sisters gathered to hear their younger brother out. He confessed that he had already proposed to the young lady.

“She is younger than you, isn’t she?”

“Not too much younger? No cradle-snatching?”

“Have you seen her birth certificate?”

“She’s not pregnant already, is she?” my youngest aunt, Amy, wanted to know. She was a few years older than Khurshed and the closest to him in childhood as they were the babies of the household. Amy isn’t a Parsi name, and my grandparents’ fourth child had been named by her elder sisters who happened to be reading Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women from which they had plucked the name.

“Well, is she?” Amy asked again.

Khurshed frowned and shook his head as though he and Amy were still children, and he was warning her off that sort of talk in front of their seniors.

“Don’t talk nonsense,” my mother said.

“Does she have family? Where do they live?”

He had already told them that her name was Freny, and they knew her surname, which they muttered and repeated like a mantra as though a familiar family tree would manifest itself out of the air.

“No, never heard the name before,” my eldest aunt said.

They asked my granddad, who was attending to his vast stamp collection, dipping paper hinges in a bowl of water and sticking specimens that had been sent to him in a bundle into one of his thick leather-covered albums. He said he’d heard the name but didn’t know anyone who answered to it.

“Of course she’s got a family. A mum and a brother who’s just got married. Her father died ten years ago.”

“And where do they live?”

Khurshed was a bit reluctant to divulge their address but knew he had to.

“A few streets away from my flat,” he said.

“That’s a slum,” Amy said. “Last time I stayed in Bombay I had to wade through garbage coming and going from your front door, and you should put a proper bulb on the staircase.”

“Whereabouts?” my quiet aunt Shera asked.

“It’s Khetwadi. It’s a Parsi colony. Not far from where our own masi lives,” he said, alluding to my grandmother’s older sister.

“Parsi charity houses?” two of them said.

“I didn’t say she was rich. She works as a secretary. Her father’s dead, and they are living off what she and the brother earn,” he said.

“Rich, poor, we don’t care,” my mother said, in a chairwoman’s tone. “And we are not snobbish about them living in a Parsi colony.”

That was the word universally used in western India for groups of buildings that rich Parsi philanthropists, some of whom had amassed fortunes in the opium trade to China, had built for the poorer families of the community. These buildings with four or six flats each, with twenty or fifty such buildings to a compound, were dotted around the whole of Bombay, and with a tight-knit community such as the Parsi Zoroastrians of India, one was bound to know many of the families. Any Parsi family tree would have some poor branch with a “colony” address.

That evening we cousins were each given a rupee by Khurshed as extra pocket-money—Bombay largesse and a fortune to each of us.

It being the hot season, we slept on the veranda on mattresses on the floor, and the collection of cousins discussed the matter in hand.

“Mamu wants to get married to his girlfriend.”

“Then there’ll be new cousins,” the youngest amongst us said.

“That’s only when they sleep in the same bed. That’s how cousins are born,” said my sister.

“Of course not. Lots of people sleep in the same bed, look at the six of us, we are not going to wake up with babies, are we? It’s the priest who says secret words and puts babies in the stomach of mummies. They can only say the secret words when they are marrying someone and have been paid already. My aunty told me,” our eldest girl cousin said. It seemed a decisive opinion.

A group of gas-lamp carriers heading for a wedding procession somewhere in the city cast a chiaroscuro of moving shadows of pillars, posts, the shapes of the bougainvillea bush, the wrought-iron trellis of the neighbours’ veranda and the shadows of passers-by on the wall opposite where we slept. The distraction of this “cinema” ended the discussion.

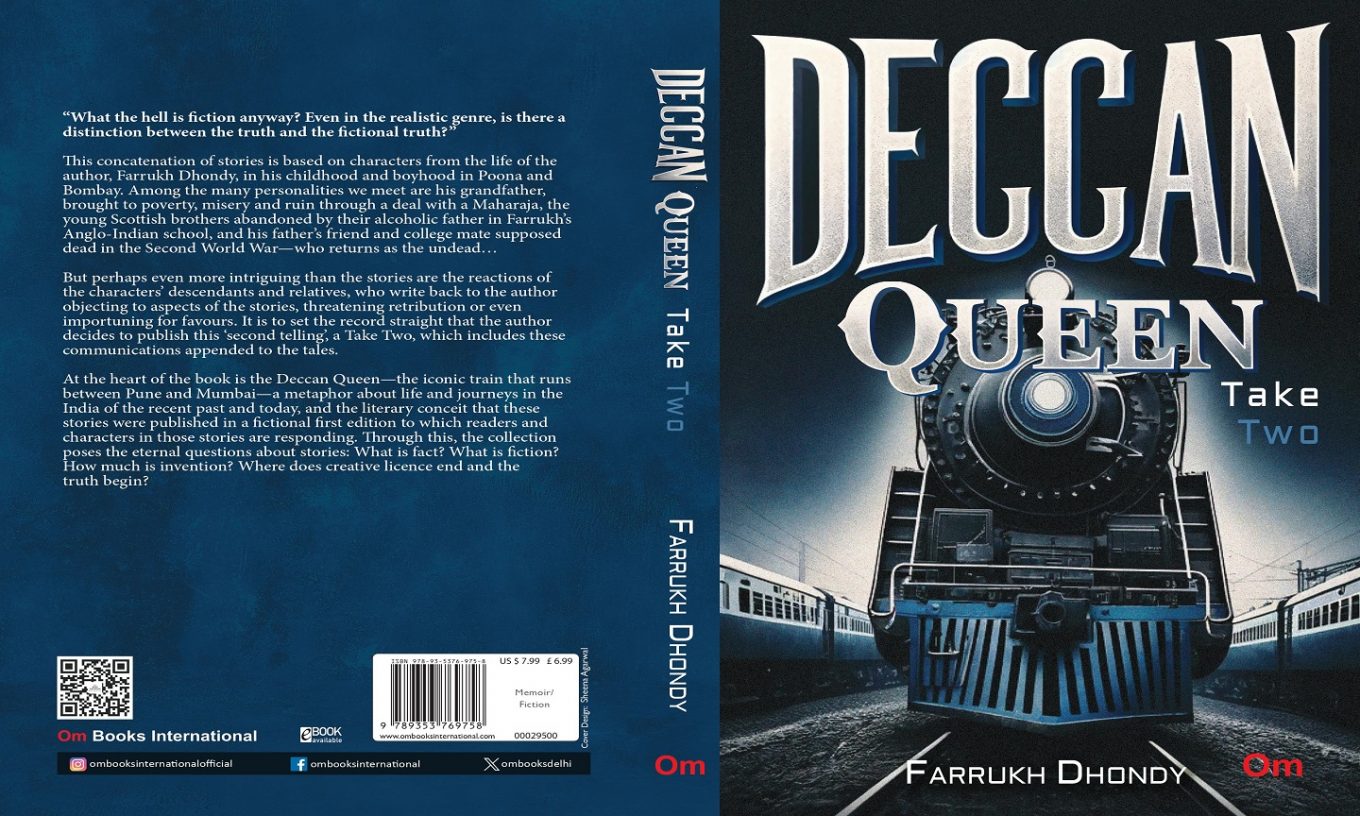

Two days after the family confab, my mum and my eldest aunt, Mani, the married one (named after the third-century Zoroastrian heretic who divided the world into good and evil and gave rise to Manichaeism), travelled to Bombay on the Deccan Queen to check out the family of the young woman who would, with their approval, become the prospective bride and would have her relatives visit us in Poona on a reciprocal family-approval mission. We woke up early to see them off before we bathed and changed into our school uniforms.

They spent four days in Bombay and returned, without Khurshed, in time for the weekend family gathering. Everyone was eager to hear their report.

I wasn’t, at the age of eight, invited into the conference, but we children were just as curious as the rest and found ways of hanging around and eavesdropping.

“She’s pretty, very nice, well-mannered, not terribly well read—she didn’t know who Jane Austen was,” my mother said.

“I don’t know who Jane Austen is. I don’t watch too many American films,” my uncle Dorab, always called Dolly, said.

“The nineteenth-century writer,” my mother said severely.

“How would I know? I don’t read Shakespeare’s novels!” Dolly said.

The conference should now have been persuaded that a familiarity with English literature was not a necessary criterion for marrying into this family.

“And her family?”

“The mother is what you’d expect, an old-fashioned Parsi lady still wearing a widow’s dark sari in the old-fashioned style. Doesn’t speak English…”

“Neither could Mamma,” Amy said.

“Yes, but she could bargain with the egg-seller in Marathi and with the fish-monger in Hindi,” my aunt Shera said.

“So do we approve?” Dolly asked.

“Yes, I think we do. And Khurshed really likes her so…” My mother shrugged. “I’ll tell Pappa.”

“So where did you meet them?”

“We were invited to their house for dinner the first night. And they’d gone to a lot of trouble,” my aunt Mani said. “I think they’d bought new crockery just for us because the paper label with the price was still stuck on the bottom of my plate.”

“That was very sweet,” my mum said. “And of course they all said that Freny had cooked the meal, all of it, all by herself. It was a feast. Very good dhan daar and Bombay Duck and bhida par eeda.”

“And this brother and his wife?”

“They live in the same flat, so they were there for dinner,” my mum said, smiling and frowning at the same time. “Bit of a strange fellow because all through dinner he had this unopened can of asparagus with him, and he kept picking it up from the table and thrusting it towards us for our attention and saying ‘Asperogers, asperogers!’ He seemed very proud of it.”

“Did he open the tin?”

“I thought he might, but he’d just brought it to the table to show us.”

Later that night, when my mother was reading to us before bed I asked her what asperogers was.

“It’s called asparagus, a kind of vegetable, a sprout, which is imported. You wouldn’t have seen it, it’s green and knuckly, but I don’t think it grows anywhere in India.”

“Then why was the brother showing you the tin? Is he a fool?”

“You shouldn’t have been listening to grown-ups’ talk,” Mum said.

“But if he’s a fool, why are we letting Khurshed Mamu marry his sister?”

“Of course he’s not a fool, darling. He’s very clever. He works in a bank. He just likes Khurshed and wanted to show us that he knows about and eats foreign delicacies, and I suppose wanted us to think that it was quite expensive. He was trying to impress us, bless him. He must have got it specially from one of those smugglers who sell you foreign junk on Grant Road.”

Smugglers! In school we had recited a poem about smugglers and had to learn it by heart. When my mother turned out the light and left us to sleep on the veranda, I remembered it, and the rhyme went round in my head.

Four and twenty ponies

Riding through the dark

Brandy for the parson

‘Baccy for the Clerk

Laces for a lady

And letters for a spy…

And asperogers for the man in Bombay who wanted his sister married into the right family.

Falling asleep I watched the wall with its rapidly moving shadows as the headlights of cars went by.

***

(Miriam, a letter from Canada disputing my account—perfect for what you wanted for the Second Edition – fd)

Toronto,

Canada.

Dear Mr Dhondy,

Having read a review of your recent book I took the trouble to order and buy it online.

I was aware that I was distantly related to you through the fact that you were the uncle of my mother’s cousin—but I am told that all Parsis can find such connections if they keep at it and allow their family-trees to spread like the Indian banyan, sprouting roots out of branches. I was proud of the fact because I too want to be a writer and am taking a semester in creative writing at my Canadian School. No longer.

I think you are scum. You misuse the medium of prose and of the past recollected in tranquillity when you write about my grandfather in a callous and abusive way in the “story” or section which you entitle “Asperogers!”

Yes, that gentle, gentle man was my grandfather—my mother’s Dad and one of the most affectionate and caring people I have ever known.

Albeit, I only knew him when we visited Bombay—or Mumbai as we must learn to call it—when I was five and six and then eleven and fourteen. The last time we went was to attend his funeral, a sad and even, for us Canadian Parsis, a curious if grim affair at the Towers of Silence.

I’ve read some of your earlier books and always thought of you, at least as a writer, as moderately sensitive. But here you were abusing my grandfather, poking fun at him, basing a whole episode of your not-too-engaging book on his mispronunciation of the word “asparagus”. Yes, so Indians and others do mispronounce words but the attitude of your family to this small mistake of a kind man was, to say the least, snobbish and callous.

Did your mother and her sister not have the grace to look beyond a vegetable can? Did they not understand his enthusiasm and possibly even gratitude towards the young man who had made an approach to be his brother-in-law?

I did meet your uncle and of course my grandaunt and they were very hospitable. My mother’s cousins are still in touch and one of them has indeed migrated to Canada as my mother and father did soon after they were married.

My sister who is a lawyer says we can’t sue you because you can’t be held for libelling the dead—and my grandfather is dead.

Perhaps you can reply to this with a tiny heartfelt apology for the hurt you have caused my mother and my family? Or is that beyond those who choose to call writing their profession? Does all heartlessness go with the job?

Repent!

Your reluctant “relative”,

Naju Watchmaker

***

London

Dear Naju,

I am pleased to hear you have abandoned the ambition to be a writer and given up on the creative writing course.

I am pleased because you’ve probably saved time to get on with other things instead of wasting it on creative writing courses.

Your complaint about my account involving your grandfather indicates that you shouldn’t be a writer. You don’t have the insensitivity for it.

I wish you the best in whatever else you choose to do.

Ever

Farrukh Dhondy