Throughout history, poets have engaged in the art of listening, of re-telling of stories, and of recounting from memory what often becomes the most important reminders for history. It is from this place of immensity, of using poetry as a coded language, and engaging in truths that continue to simmer under the surface, that we find two important women poets, Sophia Naz and Monica Mody initiate a conversation with the idea of placing poetry as a counter to amnesia and loss.

***

Sophia Naz: There are many parallels between us. Your family migrated from what’s now Pakistan to India and mine migrated in the other direction. We have similar wounds and here we are, talking on the eve of the triumphal moment of a majoritarian narrative, one monolithic story built upon the obliteration of all others, so I thought it would be apt to start the conversation with the idea of poetry as a counter to amnesia and loss.

Monica Mody: Yes, especially amidst moves to extinguish or corrupt memory—and when the realm of the unsayable is immense—poets have always had ways to tell it slant. I am thinking of poetry as coded language, speaking/holding truths that continue to simmer under the surface, and when someone has the ears to listen, they trickle or tumble out.

Sophia Naz: We really do need what the sadhus would call the Sandhya Bhasha, or twilight language, the coded utterance which the Bauls use. In that context I wanted to delve more into your source code because you have an MFA but your poetry does not reek of academia, you break all the unwritten rules of contemporary poetry that say avoid the abstract, write only in concrete terms etc. etc. In every raga there’s a pakar, a signature set of notes that creates a mood that allows you to enter into the universe of the raga. What is that pakar for you?

Monica Mody: Perhaps the imperative and capacity for self-renewal would be my pakar. During the years I lived in Delhi, I had different concerns, and I was writing from a different place and in a different register. Then I came to the US. The MFA program I attended at the University of Notre Dame allowed for and encouraged radical experimentation with form, language, and genre. I was able to familiarize myself with avant-garde currents in art and literature cross-culturally, and any static ideas about what I thought a poem could do exploded during my experimentations at Notre Dame. My book Kala Pani is written as a cross-genre text—it invokes the screenplay as a key genre, but embeds many other genre gestures. I was thinking about the trees in Kala Pani as I was reading about the banyan tree and the bird in your poem from Pointillism—these trees also come face-to-face with propaganda and surveillance.

Sophia Naz: “The Tale of The Incarcerated Tree and the Arrested Pigeon” was inspired by a newspaper story. One of those instances where truth is stranger than fiction. I had read this new report of a pigeon that had flown over the border from India to Pakistan or vice versa and it was arrested on suspicion of being a spy bird, there was some kind of a message tied around its ankle.

Monica Mody: That is dystopic!

Sophia Naz: I do feel that the capacity of poetry to defy the constraints of normative language and logical narrative makes it most suited to encompass the absurdity and horror of our times. The relationship between trees and birds has always fascinated me because it is symbiotic, despite the vast differences in their nature. It’s something humans could learn from. I also feel that “ the bird’s eye view” is somewhat akin to the clarity of perspective that occurs in a contemplative practice of writing. It’s no accident that the literature and poetry of Asia is replete with avian characters. There are the Panchtantra and Jataka tales, the Śukasaptati, or Seventy tales of the Parrot; The Conference of the Birds by Fariduddin Attar comes to mind and of course, the polyglot poetic genius Amir Khusro was given the title of Tuti é Hind or Parrot of India. I am currently writing a novel in the form of a prose poem whose first chapter is narrated by a banyan tree and the second chapter is narrated by a tilyar, a migratory bird that flies from Siberia to India and Pakistan, its name derives from til, sesame seed, a small bird, considered a delicacy and hunted down. In Pakistan, the term tilyar is also a pejorative term for a migrant from India. I think it’s impossible to overstate the profound inheritance of loss that comes from being a child of parents who grew up as Indians, were painfully uprooted from their home by the tides of identity politics, and then, till their dying day, suffered the continual fracture of that beloved motherland being labeled an ”enemy”. Very soon we will become nations whose citizens have no memories of a shared past. So much has been lost but whatever is floating around in my head in the form of received oral histories comes through in my writing.

Monica Mody: Yes I see you doing that in your work, pushing back against these myths—these wholesale myths within which we are moving—and working with them on a sensory level.

Sophia Naz: There’s a wonderful Urdu word called hassâss, sensitive is the closest word in English but it doesn’t quite capture the meaning, it means having all your senses alive, which is also what I feel in your work. There is incantation, invocation, elemental osmosis, there are none of these separations between human/animal/earth that normally occur and none of this linear narrative, there is primordial narrative or mythic narrative and something else, there is another image that keeps coming up is that snake, that snake-like circularity, there is no beginning and ending because we are just one point in the continuum right? There isn’t a sense of containment or finality in any of the poems. Even though obviously on the printed page there is an ending. Speaking about poetry as a whole I feel there is a kind of tension between the oral and textual, I mean we come from an oral tradition and in a way print is very reductive and the only way to bring it alive is to give it a second birth, the first birth is when you write it and the second birth is when you perform it. I wanted to get your take on all of this and also what is your particular entry point in conjuring these worlds?

Monica Mody: Thank you for that reading of my poems. I think it is true—my ideas about finality or closure, and, in a way, shying away from finality or closure in narrative is informed by the living oral traditions we are moving within. Our South Asian oral culture resists final and closed narratives. The poems in Bright Parallel navigate multiple strains of losses: mourning the grandparents I never met, and connected to that—the shared histories that were lost, the cultural heritage that was disrupted—how these absences shaped my relationship with my mother—the stories that did not come through to the family. In a way I rewrote myself in each of those poems, as well as my relationship to being a woman, poet, scholar. The motif of the serpent does come up again and again through the collection—although it was not like I was consciously tracking this. The idea of the snake shedding its skin and continually becoming—for me, this is an intensely spiritual idea. In the secular, linear, modern world we think we have to get somewhere, or perhaps that we have arrived. I am much more interested in the spiral and the depths and the subterranean layers—but also that there is more to open to—this could be energy, earth, ancestors, goddess, nature. For me, the poem is in some ways a zone of communion where many meanings and horizons can be attained, because, the way my brain works, no monomyth settles it. I am continually doing the work of seeing who I am in relationship with, who is before me inviting me into the task of becoming.

In the poem “The Witch on my Grandmother’s Mountain” from Bright Parallel, I invoke and talk about my encounters with the imaginal/ancestral entity Tusheeta, who taught me so much about her own time.

Sophia Naz: I see that poem as inhabiting a liminal space, akin to being between the shore and the sea where, even in nature, most of the possibilities arise, because you have the interaction between the sea and the earth, what is fluid and what is what we think of as stable and there is the element of flux and time embodied by waves. I have always felt that I am standing at the edge of English, it is still English but there is also Urdu and Hindi and the confluence of these streams is what I am drawn to explore. Using these apparently disparate languages as a means of decolonization because a great chunk of English has Proto-Indo-European roots many parts of it are the same as our mother tongues and we can, if we dig deeper realize that it’s not an other, all this English we were taught in school of Byron and Keats and Wordsworth and Shelley we can transform it, we can renew it in a way that is more feminine, more sensual, more open, more playful. Ultimately isn’t it all Leela? For centuries the central aspect of our devotional ethos is that its most enlivening interactive public expression has taken place outside the temple, it has blurred the lines between worldly and sacred space and that expansion, until recently, allowed a beautiful permeability, a porous faith where everyone could breathe. As poets, we have to once again be keepers of memory, have to remember that before Jaii Shri Ram, it was Ram Leela. Wherever there’s a play, there’s a dialogue, there’s back and forth, there is possibility. Possibility is the crux of poetic language, you just have to be there on the edge. Where now it’s kind of unsafe.

Monica Mody: Yes, and I see you do that in Bark Archipelago where it’s not an analytical process, you are not taking apart language, it’s not a sterile process, rather you get into the skin of the language and what language does there is so interesting—a few different things could happen—which is why I love following your poems in their movement because I don’t always know where they are going to go. There are moments of great whimsy, and suddenly the language conducts you elsewhere and your breath stops before you can release it—we say aah in Urdu—the moment a sigh is wrenched out of you, and it is really beautiful. Please tell me about your growth as a poet—your serpentine path—was it serpentine?

Sophia Naz: Definitely serpentine. I left home at the age of 21. I was really desperate as a teenager because I felt that no one understood me, but luckily I found a mentor in my art teacher, Nayyar Jamil who encouraged creative expression. She had a wonderful library and introduced me to the major Latin American poets. That opened up a whole world and made me realize that my life in Pakistan was too narrow and confined. I also knew that sooner or later I would be pressured into an arranged marriage. Meanwhile, due to the catastrophic military coup in Pakistan, my father lost his job as the Secretary of Health for the Northern areas because anyone who had secular views was pushed out by General Zia. So, instead of attending the National College of Art on a scholarship I ended up going to work at nineteen as a flight attendant to support my family. I eventually transferred to New York with that job and continued my writing but could never go to college. I did enroll in the Summer program at Naropa University in 1989 where I had the good fortune to meet and listen to the Beat poets, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman but essentially I am a self-taught poet.

Monica Mody: And an artist.

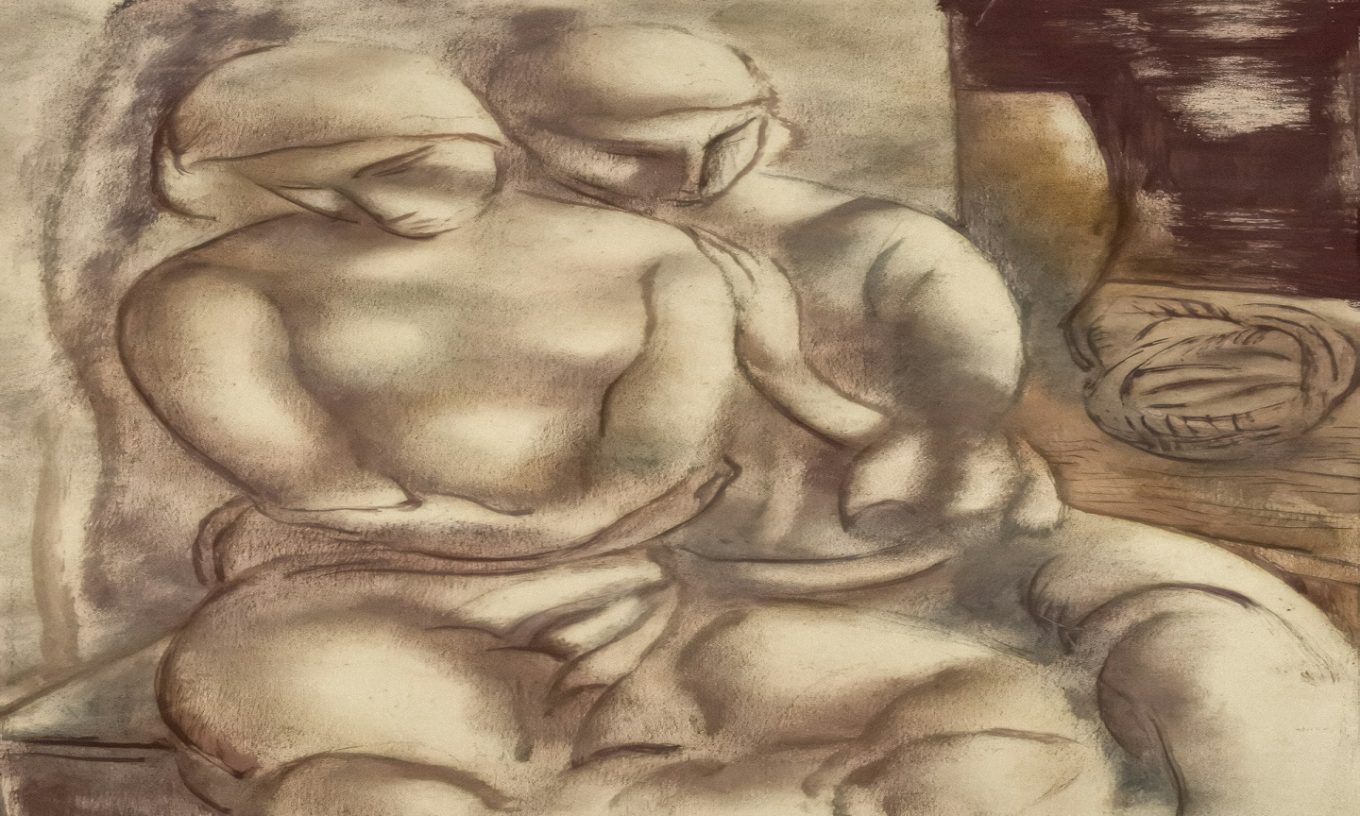

Sophia Naz: Pursuing a career in art requires a lot of resources. The only art class I could afford to take in New York was Sumi-é with the trailblazing female artist Sensei Koho Yamamoto. It was right near her studio that I met my husband Raam, a master practitioner of the Tantric pre-Vedic technique of Kayakalpa. I jumped right into that river, I have been practicing it for the last 34 years and some of that practice informs my poetry. Painting is still one of my passions. This is my trancelike interpretation of Bon Bibi; she is a forest Goddess revered by both Hindus and Muslims. This painting is inspired by my early memories because we were living in Dhaka pre-1971. Some of the poems in Pointillism allude to that period. In this painting, Bon Bibi has one eye and she is part animal and part vegetal, a lot of my paintings are like that. The title of Peripheries, my first book is a double entendre, Peri refers to an archaic spelling of pari or fairy so these are the winged women, women with magical powers, reflecting my fascination with birds and the freedom of flying.

Monica Mody: In my new poetry collection Wild Fin I am making a similar gesture—I have a long poem about yoginis and animals, imagining the relationship of trust, mutuality, and learning between the yoginis of yore and animals.

Sophia Naz: Goddesses have always had their sacred animals. In 2010 I went to Baluchistan and made a documentary on Shakti Peeth, related to the myth of Sati. Uniquely at this site, Sati overlaps with the Sumerian Goddess Inanna, who is a serpent Goddess. In fact, the temple is still called Nani Mandir, Nani being the local form of Inanna. In the myth, Vishnu chops Sati’s lifeless body into 51 pieces with his sudarshan in order to stop Shiva from destroying the universe in the grief and rage of his Tandava. The Shaktas believe that the 51 letters of the alphabet sprung up wherever Sati’s body fell. In The Alphabet Versus the Goddess the author Leonard Schlain argues that patriarchy became ascendant by written edict as opposed to the embodied goddess, but he doesn’t mention any Indian myths so when I discovered the Sati myth I was amazed because it is precisely when the Goddess is dismembered then you have language! Sati’s head fell in Hinglaj which besides being a Tantric site, is also where you find speakers of Brahui, a Dravidian language so ancient that it not only has striking similarities to Tamil but also to the aborigines of Australia! Each of these sites is associated with a particular sacred power, the most potent is in Assam where you don’t have an image of the Goddess you have a giant vulva, actually a cleft in the rock which flows red with blood in the first monsoon, revered as the sacrament of the Goddess. Menstrual blood of the goddess as a sacrament, which immediately reminded me of the blood of Christ? Maybe this is the origin story? I guess I am digressing.

Monica Mody: Or not! The re-membered feminine and language remembered as still connected to the mystery of the world, bearing the potency and possibility of rebirth. For me too, my encounter with gynocentric tantra was necessary to help sew parts of the goddess together, to recover her in a way that made sense to me. The goddess re-mythologized. For example, in my poem “Sarasvati” in Wild Fin. What is fascinating to me about Sarasvati, the goddess, is that we meet her in most of her iconography as a graceful, almost coy figure—put-together—in a sari, hair well-combed, while carrying the instruments of art, music, and learning. But the river in the Rig Veda is described as uncontrollable, untamed, mighty. So, what happened as the river became the goddess? In the poem, I try to retrieve wildness as an aspect of voice and learning, by invoking Sarasvati the river goddess. We were talking earlier about yoginis, Sati, and the Kamakhya temple–and, in their lore, there is often a closeness to the animal realm, a closeness to the nature realm. There are different streams of ‘Hinduism’ now, some of them with a sanitized version of the goddess. Another goddess that had called to me was Sarpayakshi or Nag Devi—I started thinking of her because my family now lives in Bangalore, and there are snake stones everywhere in Karnataka. There is also a small Nag Devi temple annexed to the apartment complex where they live, and the Devi here is almost weighed down in heavy silk saris—which cover over her original form. I get a lot of creative and spiritual fuel from the links between goddess, nature, earth, and creativity–fierce and regenerating creativity. The way I hold it, form is not given to her by a god–the goddess finds the form depending on what is needed in the world, upon the earth.

Sophia Naz: So different from the domesticated Goddess, a by-product of the ongoing sanitisation which started in the Vedic age, because where are the Yakshis now? Where are the tree spirits? Where are the ancient animistic beliefs that are indigenous to India? Everything seems to be more and more reductive and one note now, I find myself recoiling from it. My work is filled with deep despair sometimes because I feel there is no one really listening to voices that are alternative to the strident mainstream. What are your thoughts on that?

Monica Mody: I was teaching a graduate class on ritual and the mythic imagination yesterday. I think if writing were my only avenue for change in the world, I would feel more despair… but something happens in the classroom when a group of people come together. The ideas can move around and be breathed into possibilities—we have a lab where we can see change enacted. I feel the call for me today is to not write only for myself—it’s almost as though I have to believe as I write that the world is changing. I no longer believe that change can only happen through modes of democratic or oppositional politics… I feel those modes of thinking are very limited.

It’s very much a question of philosophy. You talked about the animistic beliefs of India—these are found everywhere, undergirding a real sense of interconnectedness where we know ourselves to be a part of the cosmos. A question came up yesterday during class, what about Trump and those who support Trump? I said, well, one of the problems is the “us vs them” paradigm that our brains automatically trap us within—we have been enculturated into this—but I feel I am trying to find something through my writing that allows us to move beyond this us vs them. I know language fails, etc, but I still feel there are so many layers, and also there is still so much that I haven’t spoken, to myself and to others. I feel there is so much to be done and there’s just not enough time.

Sophia Naz: The first line in Bright Parallel is: “Beloved, rise like a star in the firmament!” I think the answer is love, who can say no to love? Even Trump is acting out because his father most likely didn’t love him. It’s all about love. The animistic shamanic familiar, what was that line of Mary Oliver, the soft animal of your body.

Monica Mody: I see a lot of rage and grief in your paintings about Palestine.

Sophia Naz: Most of my heart and mind space is taken up by what is happening in Gaza, also what is happening in India and Pakistan. I am grateful to have gotten political asylum and to be here and be safe, but gosh, I feel my subject matter is there and the distance is painful. I do want to do more explorations of rootedness and place and in a way I feel that kinship with you because we both come from histories of uprootedness, so I am drawn to the idea of healing as regrowing roots, which is why I’m drawn to the banyan, it has aerial roots that spread horizontally. We are those banyans with roots that have spread horizontally across the seven seas.

Monica Mody: Roots and resonance.