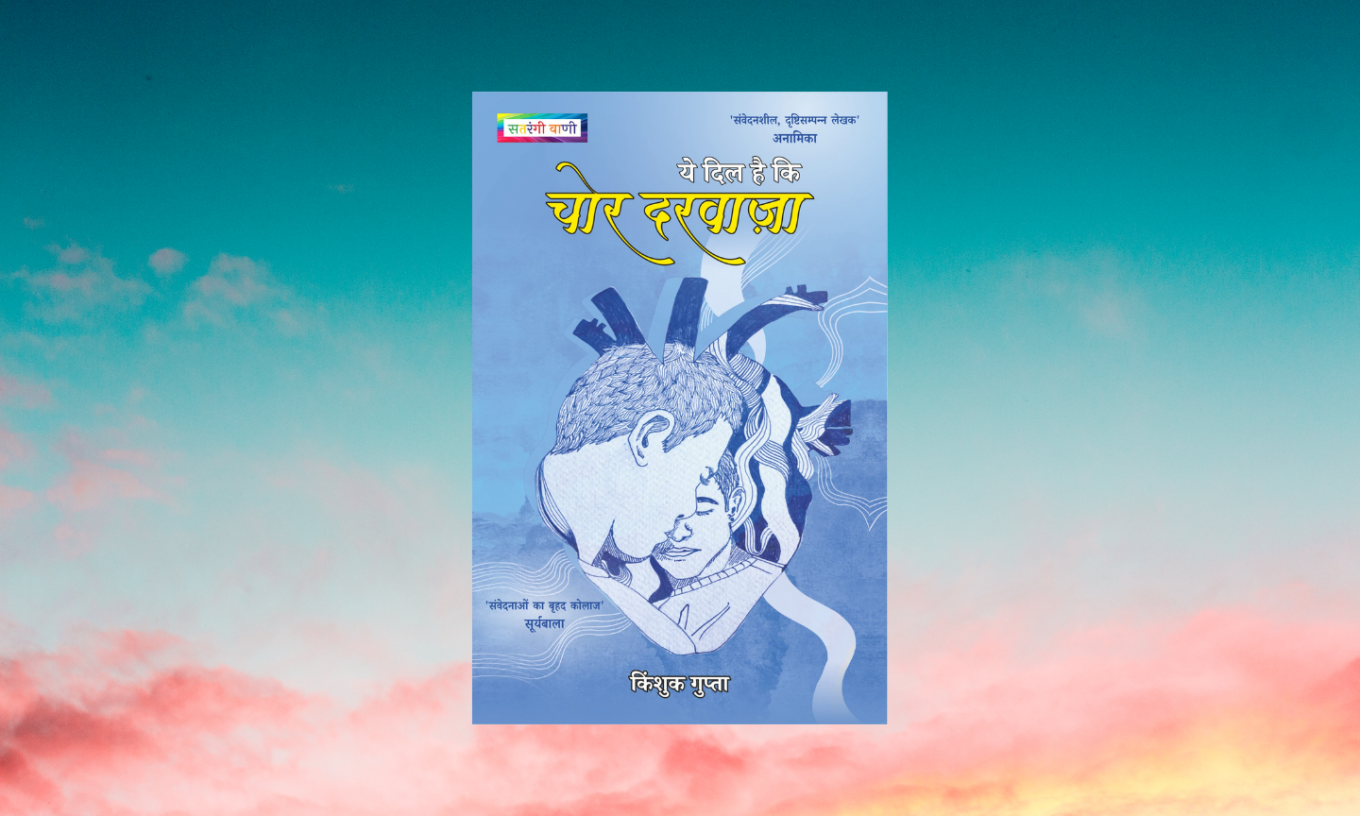

Kinshuk Gupta is a doctor, bilingual writer, poet, and translator based in New Delhi. He has been awarded the Dr. Anamika Poetry Prize (2021), Ravi Prabhakar Smriti Laghukatha Samman (2022), and Akhil Bhartiya Yuva Kathakar Alankaran (2022). He has been longlisted for the People Need Change Poetry Contest (2020), The Poetry Society, UK; Toto Awards for Creative Writing (2021) and shortlisted for the All India Poetry Competition (2018); Srinivas Rayparol Poetry Prize (2021); The Bridport Prize (2022). Gupta edits poetry for Mithila Review and Jaggery Lit and works as an Associate Editor for Usawa Literary Review. His debut book of short fiction, Yeh Dil Hai Ki Chordarwaja, the first modern Hindi LGBT short story collection, is published by Vani Prakashan. He has been working with Tishani Doshi on his debut poetry collection.

***

TBR: While your book deals with the topic of LGBTQ relationships, what I find interesting is the fact that, at a base level, these are stories about vulnerable people, who are as strong or as vulnerable as others. And perhaps inadvertently speaking it is also the most effective way of normalising such relationships?

Kinshuk Gupta: How can one harness the fullest experience of being human without vulnerability? Being vulnerable is to feel and experience. To let the heart waltz in ecstasy. To allow the vessel of the body filled with pain and grief. To retreat inwards towards oneself, towards the truth. The samaj, however, often opposes it, conflating it with weakness. Dinkar writes, in his introduction to Urvashi, samaj mein naqab ke bina aane ki samaj ki taraf se manahi hai. The interpretation of the mask, to me at least, is of conformity and compliance. The assertion of queerness, in itself, is a conscious attempt to move away from turning into watchdogs of society. This is also the reason why society is averse to queerness — which was conceived to propose an alternate viewpoint to the existent heteronormative, majoritarian views.

Queer ideology can’t be limited to sexual orientation but extends to, and even questions, all strands of interpersonal relationships. I wanted to record the contradictory responses of the Indian middle class. The Indian middle class isn’t downright disparaging of it. They want to accept it but their social conditioning won’t allow them. For example, the abrupt and absolute refusal to accept her son’s queerness makes Mrs Raizada of Mrs Raizada Ki Corona Diary questions her own 40 years of a loveless marriage.

At the same time, it was equally important for me to depict homosexuals as ‘functional beings’ — to not pin them down to their sexual choices but make it a point of conflict as they work, live and deal with difficult situations.

TBR: Your book not only talks about relationships, but also the various layers, complexities, and problems within them at large. I think the actual success of the book lies in this layering, of looking at these relations from a humane angle. Your comments?

Kinshuk Gupta: Lately, I have been reading fiction — more in Hindi — where homosexuality appears more like an entry ticket to the left–liberal, pseudo-progressive writers’ lobby. I can’t help but quote Rajkamal Chaudhary’s much-talked novel Machchli Mari Hui, considered to be the first Hindi lesbian novel, hinged on the fact that lesbianism is caused by wanton desires. What does such fiction do except help publishers stuff their pockets with crisp notes? Moreover, in the kind of Google-able world we inhabit, where a large influx of information is just a tap or click away, it’s an important function of literature to explore, to probe deeper into humans and their interpersonal relationships.

The actual representation can only come from a complex, in-depth exploration of the messiness of desires, the intense yearning to love and belong, and social repression — which could allow a person sitting in some distant town to feel a moment of instant recognition. Nuance is a necessity, not a condition.

TBR: Your book is a sort of landmark in Hindi publishing, because of the subject matter. What are the reactions you have received with regards to the book in the literary circles, as well as amongst regular readers?

Kinshuk Gupta: The reception of the book, and even my writing for that matter, remains coloured with people’s standpoints on homosexuality. In Hindi, where an entire short story collection to be based on homosexuality was rather a novel proposition, I’d say that the initial reaction was dismay. A new writer was emerging all too quickly — thanks to Sanjay Sahay and Arun Dev, editors of Hans and Samalochan respectively, who published three stories each just in a year — with no Hindi linguistic background, who was writing about sexuality. Readers were quick to dismiss me as a writer of sensational, sexual stuff. One of the readers even told my journalist friend, her eyes wide and forehead split into creases, that this boy will neither become a good doctor nor a writer because he is writing when he should be focussing on studies — and writing about such ‘shameful stuff.’

The acceptance has come gradually when people began engaging with my stories without preconceived notions. Even the credibility that came with advance praise, excerpts and a reputed publisher can’t be overlooked.

TBR: In a manner of speaking, the short story is not as popular as a genre with publishers( at least with English publishers). Is the scene different in Hindi, and do you think writing these numerous stories gave you an advantage over maybe writing a novel.

Kinshuk Gupta: As far as market dictates are considered, the situation is quite the same. The Hindi scene might be marginally more accepting of short fiction and poetry but that’s about all.

On a personal level — and as a new, emerging writer that I was at that time — writing short stories served me best. Short stories are economical, nimble, and allow a much larger room for experimentation. I could juggle with POVs and work with different structures. Thanks to the short stories, I am more convinced of my voice (and even my talent) to pull up a novel.

TBR: Your book not only delves into those from the LGBTQ community but also talks about others. How this other half deals with their emotions, their perceptions about those from the LGBTQ community, their desires, and their conditioning. Your comments, please.

Kinshuk Gupta: While the ‘other half’ might not be a statistical reality, I’m happy that the book allows that kind of conversation. I’ll come back to my previous answer to say that queerness proposed a radical change to combat the collective unconscious. The ‘other half’ not letting the comfortable clothes of their patriarchal, capitalist conditioning ripped apart, resisted change — but, even in the process of doing so, are forced to question, and in some instances, change their beliefs. Such transformation mirrors the queer experiences of growing up & coming to terms with their sexuality. On a basic, experiential level — an effect which my stories try to imitate — the other half doesn’t stay so but becomes a part of the cohesive whole.

TBR: In the world of creativity, people are very quick to typecast a writer. Despite being surrounded by creative people and intellectuals, the realities of being typecast are often real, how do you deal with it? And what would be your advice to other writers who might want to tread a similar path?

Kinshuk Gupta: Quite a few well-meaning critics, readers and friends have suggested that I move on to write a couple of heterosexual stories. Every time this thing comes up, I ask them if they’d do a headstand for me.

Jokes apart, these are the perils of being a writer. Moral policing that charged Manto with obscenity, or banned Lolita works this way. To add to it, even pigeonholing might not be that big a threat, as much as a young person confused with their sexuality being subjected to hate & resentment from society because of their writing — which is, in a way, the only safe space available that allows them unadulterated expression.

Whether it be Syed Haider Raza’s fascination with ‘the Bindu (the dot), or Murakami’s psychological underpinnings, the history of the arts is permeated by masters who were obsessed with certain themes. This textured repetition is what gives an artist a unique vantage point. Not to mention that writing being a mysterious act resists simple logic. On the other hand, the fear leading to conscious repression might prove to be far more detrimental to a writer’s potential than any labelling.

This is also not to say that one shouldn’t allow breaking away from their patterns, to outgrow concerns or themes, but that happens over time — and only organically.

TBR: I know it is difficult for an author to choose from their own work, but if you were asked to choose any one story from this collection that you think would be a must-read, which one would it be and why?

Kinshuk Gupta: I have a strange fondness for Sushi Girl. Perhaps because it has undertones of a mystery novel and one requires skills to build intrigue and keep the tension intact while also not confusing the reader. Stories of heterosexual marriage with gay husbands are often told from the vantage point of guilt-stricken husbands who either villainize the wives or choose to turn them into docile creatures, accepting their husband’s infidelity with reverence. Even a well-celebrated female critic told me that that kind of end would have served the story better. I wanted to do just the opposite — allow the wife to take charge of the narrative. I was afraid of appropriation, of course, but after a feminist scholar wrote back saying that a woman writer might not have been to pull up such an acute, sensitive portrayal, I was relieved.

TBR: It would be safe to say- given your literary output-that you have an equal hold on both Hindi and English. What was the reason then for writing the book in Hindi and not in English, I ask this because maybe your book would have been received by a more international audience, or were you specifically interested in reaching out to a Hindi audience? In short, is Hindi your language of intimacy?

Kinshuk Gupta: Coming from the small, sleepy town of Kaithal in Haryana, Hindi was my first language, my mother tongue. My interest in Hindi was further fortified by my grandmother’s lucid knowledge as a Hindi professor — and her irresistible, insatiable desire to read books. Her personal library, with over a thousand books, was a mix of Hindi literature, Russian literature, psychology, and social sciences books, which allowed me to immerse myself in worlds unknown to me. My vocation in Hindi has been an organic process. While I was reading Shakespeare and Hemingway and other English masters all through my childhood, writing in English felt like a purported effort. Moreover, for this particular book, my choice of Hindi was intentional as well — the Hindi literary establishment, unexposed to homoerotic writing, further strengthened by its right-wing ideology, holds prejudices against homosexuality. Homosexuality is still not considered a topic worthy of discussion, even in literary discussions. I strongly believe that the attention my book attracts will initiate a conversation that is the need of the hour.

TBR: Do you think that a book such as this should be essential reading, as a part of a college/university syllabus?

Kinshuk Gupta: Absolutely. Awareness — and visibility — employing fiction can help both queer and non-queer students alike. With dialogue, it can help in the creation of safe spaces thereby reducing bullying and alienation faced by queer students.

TBR: Given the fact that your book is an important step towards nuanced storytelling in this genre, what are the prospects of getting the book translated into other languages?

Kinshuk Gupta: My writer-editor friend Dyuti Mishra is working on the English translation of the stories. Once the book comes out in English, getting it translated into other Indian languages would be the next step.