I do not remember the last time I spent hours trying to mend something. In my teens, when a shirt ripped around the armpits or when a button was lost, it was a quick needle job.

Now I had lost patience. I was older. I had gotten used to using and throwing.

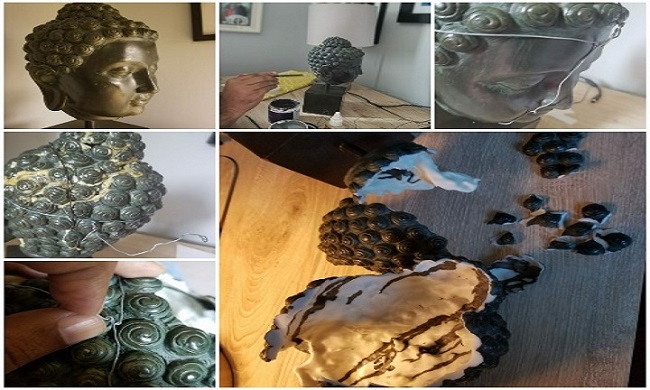

It was a snowy afternoon, almost two years ago. I remember the range of emotions that swept through me when I picked up the shattered smithereens of the Buddha bust in our living room. My four-year-old coincidentally named Siddharth had managed to get his fishing rod tangled around Gautama’s top knot. Now there was a mess on the floor and the boy was hiding under the table with terror-stricken eyes. A sense of loss? Sure. Rage? Yes.

Was it an announcement? There can only be one enlightened one in this household. For now, it would be my rambunctious four-year-old.

A cheap decorative piece that took its place in the house just about when we moved in – that was all it was. If I remember correctly, it was all of five bucks. Now the head was badly smashed in. The face had survived. Mostly. And therefore, the pieces were swept up and put away. That smile just did not belong in a garbage bag. At least, not yet!

There it sat, for almost two years until this week. This week of convalescence after yet another procedure to keep me alive.

What do you do if you are alone trying to put yourself back together? You need affirmation that things can be put back together. Out came the pile of 37 broken pieces.

I had never restored or glued back three-dimensional objects. I was no Kintsugi master. Kintsugi, also known as Kintsukuroi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered precious metals. Kintsugi teaches you that your broken places make you stronger and better than ever before. When you think you are broken, you can pick up the pieces, put them back together, and learn to embrace the cracks.

One had to start somewhere. It was easier to identify the larger pieces, where each one should be. The smaller pieces presented numerous possibilities. Over the week, my fingers became friends with each soft tuft of his curly hair. On some days, there were setbacks. Like the fourth day when I woke up to see a piece standing up from the dome, like a lock spiked up with gel. I laughed. Then that lock of hair had to be cut down again and reglued. When all the supporting wires were removed and the paint touches completed, my hands were trembling. Because they had grown weary over time, because I was worried I might break it again by accident.

I go back to work tomorrow pretending everything is okay with me. I will flash big smiles at my colleagues and do the rehearsed confident stride.

Tonight, the finished Buddha bust is smiling at me from the nightstand. If you peer closely, the fault lines are visible. Pretty much like mine.

We know nothing as to when the next big rattle would be, who will survive what. For now, we are ready for tomorrow.

Images provided by Author