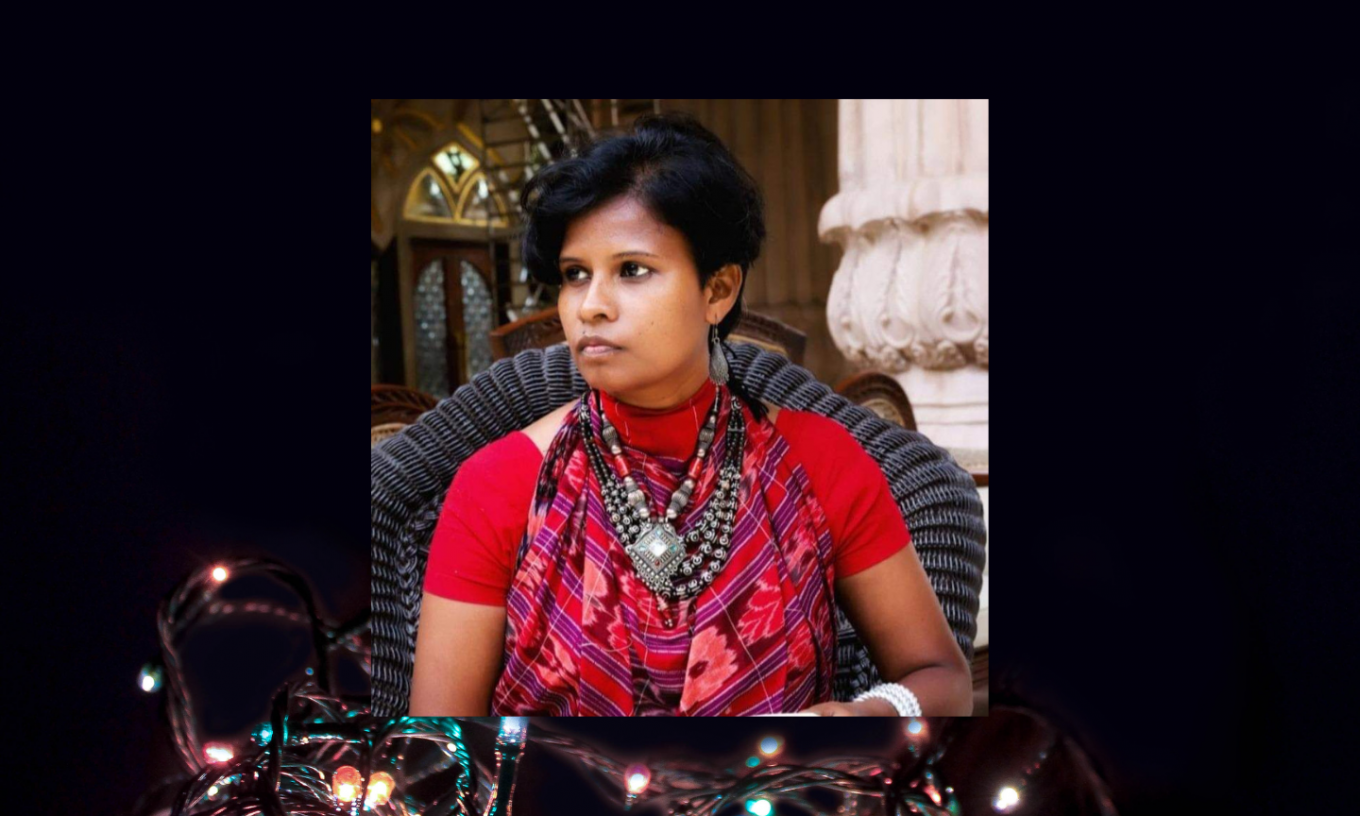

Jacinta Kerketta is a poet, writer, and freelance journalist, belonging to an Oraon Adivasi community of West Singhbhum district. She writes in Hindi. In her poems, Jacinta highlights the injustices committed on the Adivasi communities, along with their struggles. Our editor Maitreyee B Chowdhury interviewed her on the occasion of International Women’s Day.

Her books can be bought at Amazon and elsewhere.

1. How do you envisage other women like yourself in today’s world?

Ans: As a woman, I would like other women like me to be independent, confident, have the ability to make her own decisions, to be able to dream and have the ability to chase those dreams, to be courageous, to be without fear, to be free, to be financially and intellectually competent.

All of this was my mother’s dream for herself. But in her struggle to make herself financially independent, she was too afraid of what society, people or family would think. As a result, she had always mentally subjugated herself. With a lot of patience and courage, she subjugated herself to immense struggle all her life. But she has seen that I always run after my dreams. I take my own life decisions without fear. I have always tried to push myself, in order to be financially and intellectually capable enough, so that emotional ties don’t push me towards enslavement. Seeing this makes my mother happy. She tells me in fact that, ‘if I were to have another life on this earth, I’d like to live it as courageously as you do.’ My mother died with this satisfaction. I dream of the same things for each woman.

2. How different is your politics from your poetry?

Ans: My poetry and my writings are my life choices. They are my dedication, my protest. I want to see how this works within society. Writing as an Adivasi woman, itself is a political act in fact. As a result, my poetry and my politics are not really apart. All that agrees with me, is my poetry. The world view of the Adivasis can be correctly understood by sensitive people, who emerge from this very society. Maybe, I’m trying to do all that through my poetry. I want to treat poetry like a medium through which I travel the world, meet people and tell them what it means to be an Adivasi- perhaps all of this is like a sort of movement or a campaign. Talking about Indian tribes and their struggles to others around the world, and trying to connect the two together is a part of a social and political work. In this world there are only two kinds of philosophical struggles, one is in tune with nature and the other, the struggle against nature. How this thought can be articulated, felt or seen through an Adivasi lens, is what I am trying to do.

3. According to you, what do the women of this country need the most today?

Ans: I think, knowing oneself, understanding one’s circumstances and one’s dreams, that is important for us as women. Since childhood, women are taught about others. They are taught about the house, the family, society, state, country, tradition, religion- the only thing they are not taught about, is themselves. It is important that women are completely conscious about financial and intellectual aspects of their lives, while also being politically aware. All of these are important aspects because throughout history, women have been used as a shield and as a weapon, by various forces in authority, power, and politics. These are the ways through which women can identify the roads that lead to a better world, whether it is for themselves or for others. More importantly, it will also help identify those, within whom the female is still alive, enabling us to work with them.

4. Could you please tell us a bit about the impact of nature, and those people aligned with nature, in your poetry.

Ans: My poetry constitutes both nature and resistance. The Adivasi approach takes into account not only nature, but also looks into the well-being of the entire humankind. My work takes into account not only the struggle, the pain, the history, realities of land, dreams, and the attitude to life of Adivasis but also that of all other marginalised communities. There is also an effort in my work, to critically look into religion, politics and the lives of women. Poetry from other parts of the world, such as Germany, Brazil, Latin America, etc. in a manner of speaking connect their own struggles with that of the Adivasi struggle.

5. What are the areas or situations that have influenced your poetry?

Ans: The Adivasi people of central India and their journeys have given me a new point of view. Without them, I cannot see myself being successful in my journey as a writer. The hard-working people of the land have helped me in realising my choices. I can see that in reality, the actual fight is being fought by those who inhabit the land. Standing with them in their land, makes me realise the cruelty with which the State deals with Adivasis and those who are in tune with nature. The rest of the people are to be seen adjusting with the authorities. These people sometimes criticise the State to a certain extent, but also praise and live in harmony with the State. Despite their reservations, these people help in maintaining the cruelty of the State, with the small or big roles that they play in this regard. These educated people do not realise the truth about the cruel treatment that the State reserves for Adivasis or other marginalised people. They do not even realise this.

Only by standing in the land of such struggle or revolt, can one see such truths. Without seeing or living through these experiences, my poetry couldn’t have been as powerful. It is the people who have lived poetry, who have made poetry so powerful. While writing poems, often I become so restless that I cannot even sleep. Often while writing, I become tearful. It is not easy to write such poetry.

I am always indebted to my German friend and well-wisher, Johannes Laping who in the true sense lived the Adivasi life. He translated my work and travelled with me to different countries as a translator to recite my poetry along with me. Together, we recited poetry in about twenty German cities and many other different cities in Italy, Switzerland, Austria, and France. During these travels, he told me about unique stories from different lands, which gave me a wide understanding of matters. He never wanted anything for himself, except for playing a small but important role. He translated my poems and remained dedicated to them till the end. In 2021 after finishing the translation of my book of poems Ishwar Aur Bazar into German, he died. He went away rather quietly.

Documentary film maker Meghnath from Jharkhand was his friend, even Manoj Lakra, my Adivasi friend was well acquainted with him. All of them are like my family. These are the people who have inspired me to remain upright with my values intact, and helped me in warding off bad influences from the outside world. There are few of these amazing people who have shown the way for me by living their lives with universal values. My poetry is influenced collectively by nature, people on the ground, my well-wishers and their beautiful values, their struggles, their dreams and their resistance. Within this is a small part of me, and large parts of these many others.

6. Does your poetry reflect your ongoing conflict, or is it an end goal for you?

Ans: I have never thought of my poetry as an end goal, neither have I tried to achieve anything through my poetic journey. It may seem so sometimes to outsiders, but those who know me closely will vouch for the fact that outside influences have never touched my core. Poetry is like a river, a continuous journey. My role is to be aligned to the vastness of nature’s journey, and add my small contribution to this journey. If nature wants to convey something to people through its world map, it will trace that path through the narrative of poems perhaps. I feel like I am moving in the steps shown by nature, in this regard.

This is also a continuous internal and external struggle, to not let go to waste, the principles of one’s life. A few of my Adivasi friends tell me that playing around with words is not what poetry is about. They tell me that poetry needs to be without guile, it needs to retain honesty and truth. The day these universal truths vanish from the earth, poetry will vanish too. This is told to me by people who have never written any poetry, people who have no connection with literature. But these are people, who are connected to the land and its honesty. I try to always keep these thoughts within me, and I am happy that my poetry is read by such people, and that they find themselves in my poetry.

7. Please tell us something about your upcoming writing.

Ans: Till now three of my poetry collections have been published- Angor, Jadon ki Zameen, Ishwar aur Bazar. The work of translating Ishwar aur Bazar into English is ongoing, and it is supposed to be released soon enough. I always dreamt of bringing about a book for children or the youth. This year, Jugnoo Prakashan, an imprint of Ektara Trust, has released the book Jacinta’s Diary from Bhopal. The book is a diary-like account of my travels through Adivasi land, besides some short poems. The book will take children through Adivasi areas, their lifestyles, the forests, mountains, rivers and the village markets, giving them an incentive to understand all of it from a fresh perspective.

8. Is Jacinta Kerketta, a poet first or an activist?

Ans: From the time when I did not even know who is an activist, how they are made and why- I had started writing from that young an age. Which is why I am first a poet and a writer, at least that is what I think. My writing came to be infused with my activism. It did make my writing stronger though.

***

(The original version of the Interview in Hindi)

1. एक महिला होने के नाते, आप अपने जैसे महिलाओं को किस मुकाम पे देखना चाहेंगी?

उत्तर: एक महिला होने के नाते मैं अपनी तरह दूसरी महिलाओं को आत्मनिर्भर, आत्मविश्वासी, अपने जीवन में अपना निर्णय खुद ले सकने वाली, सपने देखने और उसके पीछे भाग सकने की क्षमता रहने वाली, साहसी, निर्भय, आज़ाद, आर्थिक और बौद्धिक रूप से सशक्त महिला के रूप में देखना चाहती हूं.

यह सबकुछ मेरी मां का सपना खुद के लिए था. लेकिन खुद को आर्थिक रूप से सशक्त करने की जद्दोजहद में, समाज, परिवार, लोग क्या कहेंगे के डर से उन्होंने हमेशा खुद को मानसिक रूप से गुलाम बनाए रखा. वे बहुत धैर्य, साहस के साथ हिंसा और दुःख उठाती रहीं जीवन भर. लेकिन उन्होंने देखा मैं अपने सपनों के पीछे भागती हूं, निर्भय होकर अपने जीवन के निर्णय खुद लेती हूं. आर्थिक और बौद्धिक रूप से खुद को मजबूत करने की कोशिश में निरंतर लगी रही ताकि ये बंधन अन्य गुलामी की तरफ़ मुझे न धकेल सके. यह देखकर मेरी मां बहुत खुश होती थी. वे कहती थी फिर कोई जन्म होता होगा अगर धरती पर तो तुम्हारी तरह साहस के साथ कोई जीवन जीना चाहूंगी. इस संतोष के साथ उनकी मृत्यु हुई. मैं हर महिला के लिए ऐसे सपने देखती हूं.

2. आप की कविता और आप की राजनीति में कितना अंतर है?

उत्तर: मेरी कविता, मेरा लेखन मेरे जीवन का चुनाव और समर्पण है. प्रतिरोध है. मैं देखना चाहती हूं यह समर्पण किस तरह समाज के भीतर काम करता है. आदिवासी स्त्री के रूप में लिखना ही एक तरह की राजनीति है. कविता और मेरी राजनीति अलग-अलग नहीं है. जो मेरी पक्षधरता है, वही सब कविता है. आदिवासियों की विश्व दृष्टि को इसी समाज के भीतर से निकलते चेतना संपन्न लोग ठीक तरीके से दर्ज़ कर सकते हैं. संभवतः मैं वह सब अपनी रचनाओं के माध्यम से करने की कोशिश कर रही हूं. कविता को एक मध्यम की तरह लेकर पूरी दुनिया में जाना, यात्रा करना, लोगों से मिलना और आदिवसियत की बात करना यह सब एक तरह का आंदोलन या मुहिम ही है. भारत के आदिवासियों की बात दुनिया के दूसरे हिस्सों के लोगों तक पहुंचाना और उनके संघर्ष से यहां के लोगों को जोड़ने की कोशिश करना यह सब एक सामाजिक और राजनीतिक काम का ही हिस्सा है. दुनिया में दो ही जीवन दर्शन का संघर्ष है. एक प्रकृति के साथ है, दूसरा प्रकृति के खिलाफ़ है. इस समझ को आदिवासी नज़रिए से कैसे देखा, समझा और महसूस किया जाए. यही मेरी कोशिश है.

3. इस देश में, आप के अनुसार, औरतों को सबसे ज़्यादा किस चीज़ की ज़रुरत है आज?

उत्तर: अपने आप को, अपनी स्थिति को, अपने सपनों को जानने की. स्त्रियों को बचपन से सबके बारे बताया जाता है. घर- परिवार, समाज, राज्य, देश, परंपरा, धर्म. पर खुद के बारे उन्हें कोई नहीं बताता. वे आर्थिक और बौद्धिक रूप से चेतना संपन्न हो यह बेहद जरूरी है. उनके भीतर राजनीतिक चेतना की संपन्नता भी आए. इसकी भी जरूरत है. यह सब मुझे जरूरी लगता है. क्योंकि सत्ता, शक्ति, राजनीति हमेशा स्त्रियों को अपनी ढाल और हथियार दोनों की तरह इस्तेमाल करती है. यह समझना बेहद जरूरी है. तभी स्त्रियों को अपने लिए, सबके लिए एक बेहतर दुनिया के रास्ते स्पष्ट दिख सकेंगे और ऐसे लोग जिनके भीतर स्त्री बची हुई है, उनके साथ मिलकर भी काम करना संभव हो सकेगा.

4. आप के कविता में प्रकृति और उसके साथ जुड़े हुए लोगों की भूमिका के बारे में हमें बताएं

उत्तर: मेरी कविता में प्रकृति और प्रतिरोध है. प्रकृति को देखने का आदिवासी नजरिया है जो प्रकृति के साथ-साथ संपूर्ण मनुष्यता की फिक्र करती है. इसमें आदिवासियों के साथ-साथ हाशिए के सभी लोगों का संघर्ष, पीड़ा, इतिहास, ज़मीन की वास्तविकता, सपने हैं, उनका नज़रिया है. इसमें धर्म, राजनीति, स्त्री-जीवन सबको आलोचनात्मक रूप से नए नजरिए के साथ देखने की एक कोशिश भी है. विश्व के अन्य हिस्सों जैसे जर्मनी, इटली, ब्राजील, लैटिन अमेरिका आदि जगहों से जुड़ी कविताएं भी हैं जो दुनिया के अलग – अलग देशों के संघर्ष को भारत के आदिवासियों के संघर्ष के साथ जोड़ती हैं.

5. आपकी कवितायेँ किन किन चीज़ों या परिस्थितियों से प्रेरिदत्त होती हैं?

उत्तर: मध्य भारत के आदिवासी इलाकों की यात्राओं ने, लोगों ने मुझे नया नज़रिया दिया है. उनके बिना खुद को लेखन के क्षेत्र में समृद्ध होते हुए मैं नहीं देख पाती. ज़मीन के संघर्षशील लोगों ने मुझे अपनी पक्षधरता का चुनाव करने में बहुत मदद की है. मैं देख पाती हूं कि वास्तव में असली लड़ाई वास्तविकता की ज़मीन पर खड़े लोग ही लड़ रहे हैं. उनकी ज़मीन पर खड़े होकर दिखाई पड़ता है कि स्टेट आदिवासियों और प्रकृति से जुड़े लोगों के साथ कितना क्रूर व्यवहार करता है. शेष लोग तो व्यवस्था के साथ नज़र आते हैं, उसमें एडजेस्ट होते हुए. थोड़ी बहुत आलोचना करते हुए, उनका गुण गाते हुए, उनके बीच, उनके साथ सामंजस्य में जीते हुए. न चाहते हुए भी क्रूर व्यवस्था को बनाए रखने में अपनी छोटी-बड़ी भूमिका निभाते हुए. ऐसे पढ़े-लिखे लोग भी इस सच्चाई को नहीं महसूस कर पाते कि स्टेट का चेहरा ज़मीन पर खड़े हाशिए के लोगों, आदिवासियों के लिए कितना क्रूर है. वे यकीन भी नहीं कर सकते.

संघर्ष और प्रतिरोध की ज़मीन पर खड़े होकर देखने से सच्चाई और बबल इन दो जगहों पर जीते लोगों को स्पष्ट रूप से देखना संभव होता है. इन सब अनुभवों को देखे, महसूस किए और जिए बिना मेरी कविता इतनी ताकतवर नहीं हो पाती. कविता को जीने वाले लोगों ने कविताओं को वह ताकत दी है. कविताएं लिखते हुए मैं बेचैनी में कई रात सो नहीं पाती हूं. अक्सर यह होता है कि लिखते-लिखते आंख से आंसू बहते रहते हैं. कविता लिखना आसान नहीं है.

आदिवासियत को जीने वाले एक जर्मन मित्र, शुभचिंतक जोहानेस लापिंग की मैं हमेशा आभारी हूं. उन्होंने कई देशों की यात्रा में अनुवादक के रूप में मेरा साथ दिया. यात्रा के दौरान हर जगह की अनकही कहानियों को सुनाया, जिससे मैं चीजों को व्यापक फलक पर देख सकी. वे खुद के लिए कुछ नहीं चाहते थे. छोटी और जरूरी भूमिका निभाना चाहते थे. वे मेरी कविताओं का अनुवाद का काम करते हुए कविताओं के प्रति अंतिम समय तक समर्पित रहे. 2021 में कविता संग्रह ” ईश्वर और बाज़ार” का जर्मन भाषा में अनुवाद ख़त्म कर चुकने के बाद उनकी मृत्यु हुई. वे चुपचाप चले गए.

झारखंड के डॉक्यूमेंट्री फिल्म निर्माता मेघनाथ उनके पुराने मित्र हैं, मेरे आदिवासी मित्र मनोज लकड़ा भी उनके मित्र हैं. ये सब मेरे परिवार की तरह हैं. इन सबने मुझे अपने मूल्यों के साथ खड़े रहने, बाहरी दुनिया के बुरे प्रभाव से बचे रहने में बहुत मदद की है. यूनिवर्सल मूल्यों को जीते हुए ये अद्भुत कुछ गिने-चुने लोगों ने मुझे ताकत दी है. मेरी कविताएं प्रकृति, ज़मीन के लोगों, मेरे शुभचिंतकों, उनके सुंदर मूल्यों, संघर्ष, उनके सपनों, उनका प्रतिरोध सबका कलेक्टिव परिणाम है. इसके भीतर मेरा थोड़ा और बहुतों का बहुत सारा हिस्सा है.

6. आप की कविता क्या आपका संघर्ष है या एक मुकाम ?

उत्तर: मैंने इसे कोई मुकाम या कोई मुकाम हासिल करने के माध्यम की तरह कभी नहीं देखा. बाहर से यह भले ऐसा लगता हो पर मुझे बहुत निकट से जानने वाले लोगों को यह महसूस होता है कि बाहरी प्रभावों ने मुझे छुआ भी नहीं है. कविताएं एक नदी, एक यात्रा की तरह बहती जा रही हैं. मेरी भूमिका बस प्रकृति के व्यापक मकसद के साथ जुड़कर अपना छोटा योगदान देना भर है. अगर प्रकृति विश्व पटल पर लोगों से कुछ कहना चाहती है तो वह कविताओं से होकर अपना रास्ता तैयार करेगी. मैं उसके पीछे-पीछे चलती हुई सी महसूस करती हूं.

यह निरंतर एक संघर्ष भी है, जिसमें खुद के मूल्यों का जीवन के किसी मोड़ पर छीज जाने से बचाने के लिए भीतर और बाहर का जद्दोजहद भी शामिल है. कुछ आदिवासी मित्र मुझे कहते हैं कि शब्दों के साथ खेलते रहना कविता नहीं है. उसके भीतर निश्छलता बची रहे, सच्चाई, ईमानदारी बची रहे. जिस दिन यह सब यूनिवर्सल वैल्यू जीवन से गायब होगा, कविताएं गायब हो जाएंगी. यह ऐसे लोग बताते हैं जिन्होंने कभी कोई कविता नहीं लिखी. साहित्य से जिनका कोई वास्ता नहीं है. पर वे ज़मीन से जुड़े सच्चे लोग हैं. मैं हमेशा उन बातों को अपने भीतर रखती हूं. मुझे खुशी है कि मेरी कविताएं ऐसे लोग पढ़ पाते हैं. और उसमें खुद को महसूस कर पाते हैं.

7. आप की आने वाली लेखन के बारे में कुछ बताएं.

उत्तर: अब तक मेरा तीन कविता संग्रह प्रकाशित हुआ है. अंगोर, जड़ों की ज़मीन, ईश्वर और बाज़ार. ईश्वर और बाज़ार कविता संग्रह का इंग्लिश अनुवाद जल्द ही आने की संभावना है. इस दिशा में काम चल रहा है. युवा और बच्चों के लिए हमेशा से कोई किताब लाने का सपना था. इस साल इकतारा ट्रस्ट के प्रकाशन छाप जुगनू प्रकाशन, भोपाल से ” जसिंता की डायरी ” प्रकाशित हुई है. इसमें आदिवासी इलाकों की यात्राओं से जुड़ी मेरी डायरी, कथा और छोटी-छोटी कविताएं शामिल हैं, जो बच्चों को आदिवासी इलाकों के दृश्य, जीवन, जंगल-पहाड़, नदी, हाट तक लेकर जाते हैं और नए नजरिए से इसे देखने को प्रेरित करता है.

8. जसिंता करकेट्टा, पहले कवी हैं, या एक्टिविस्ट?

उत्तर: एक्टिविस्ट कौन होता है, कैसा होता है, क्यों होता है, इन सबके विषय में जब कुछ नहीं जानती-समझती थी तब से कच्ची उम्र में मैंने लिखना शुरू किया. इसलिए कवि और लेखक पहले हूं. ऐसा लगता है. लेखन के साथ एक्टिविज्म शामिल होता गया है. इसने मेरे लेखन को मजबूती ज़रूर दी है.