Introduction:

Rajinder Singh Bedi’s story written in 1939, is a timeless story of one ordinary man who selflessly worked to save people during the Plague.

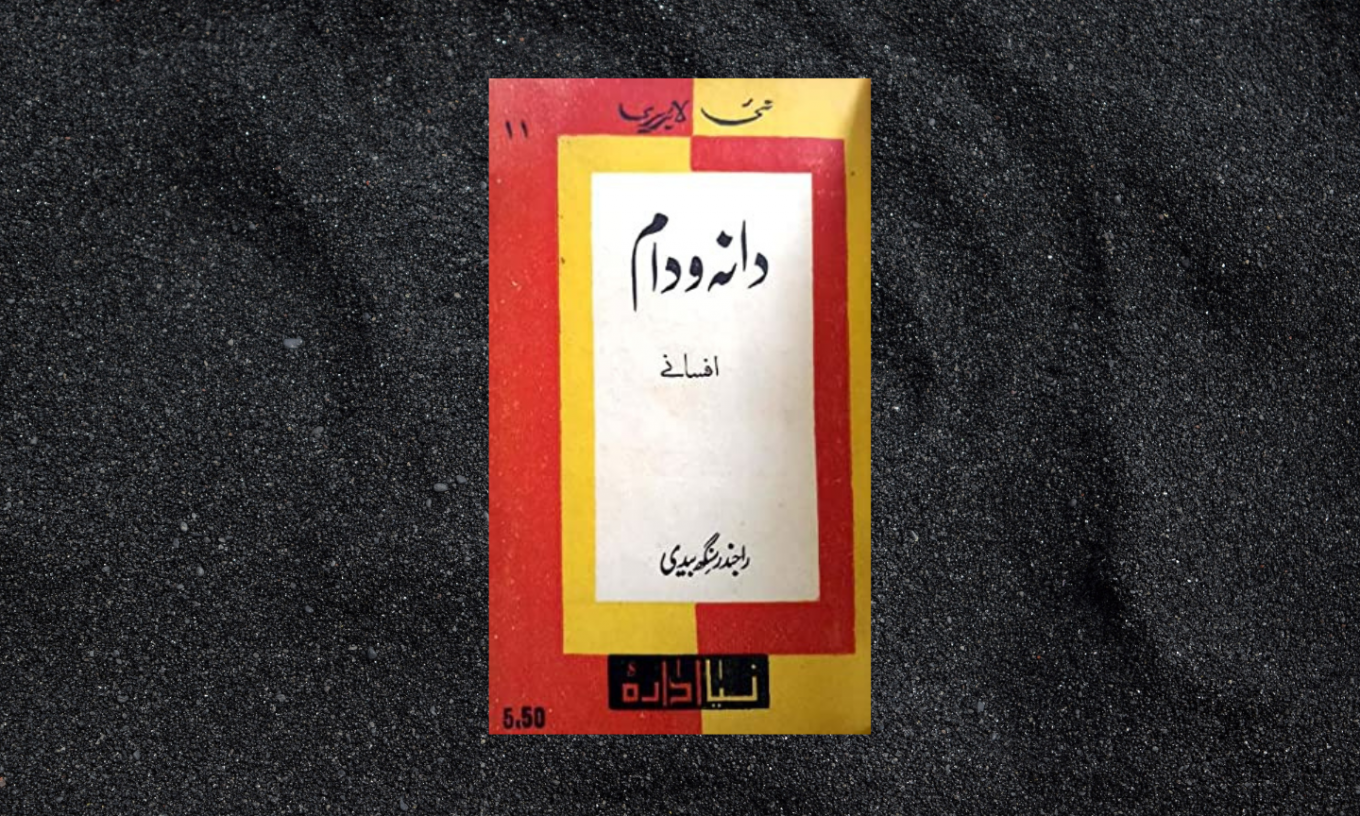

Although he was Punjabi, he opted to write his stories in Urdu and later in Hindi because his mother tongue, Punjabi, was not regarded as a literary language. This bias towards Punjabi, unfortunately, endures in much of South Asia even though Punjabi literature dates back to the twelfth century and even though Punjabi culture dominates much of South Asian popular culture. This story, “Quarantine,” was published as a part of Bedi’s first volume of short stories, Daanaa o Daam (Baited Trap), which was published in 1939. It was subsequently published in Hindi decades later as well as Punjabi. The Urdu version has been used as the basis for this translation. Both the Hindi and Punjabi versions significantly differ from the Urdu original.

The story takes on an uncanny resemblance during the current pandemic situation the world faced and from which we as a human race, are just emerging. People’s stories, the problems of middle-class lives, love and pain, inherently remain the same through the ages.

In this wonderfully translated story, we understand this more than ever.

***

Like the fog that spreads out and obscures everything across the plains lying at the feet of the Himalayas, the fear of plague stretched out in four directions. Every child in the city would shudder upon hearing its name.

While the plague, in fact, was dangerous, the quarantine was even more deadly than the illness. People were not as immiserated by the plague as they were by the quarantine. To save the citizens from the rats, the Health and Safety Department printed up life-sized banners and put them on doors, roads, and avenues emblazoned with the caption “No Rat. No Plague. No Quarantine,” expanding upon the earlier slogan, “No Rat. No Plague.”

The people were frightened of the quarantine. Given that I am a doctor, you can believe me when I claim that more people in the city died from the quarantine than from the plague. The quarantine is not a disease; but rather the name of an area where, during the days when the epidemic was spreading through the air, sick people were separated from healthy people by force of law to prevent the disease from further proliferating. Even though there were reasonable numbers of doctors and nurses in the quarantine, it wasn’t enough because patients kept coming in ever-increasing numbers. Patients were not given—and indeed could not be given—personalized care. Because patients’ family members were by their side, I saw many patients lose their mettle. Having watched so many others die, one by one, all around them, many patients died well before death. On many occasions, a person would come in with a minor illness but would die from the pathogens pervasive in quarantine. Because the death toll kept climbing, last rites could only be performed per the special procedures of the quarantine, which is to say, hundreds of corpses were strung out like the carcasses of dead dogs atop a mounting heap. Then, without any religious formalities, petrol would be tossed on the pile and set ablaze. Seeing the flames climbing up towards the evening sky, the remaining patients felt that the entire world was aflame.

The quarantine was the reason for the swelling deaths because, upon seeing the symptoms of the disease, family members of the afflicted began hiding them so that they would not be remanded to the quarantine forcibly. Doctors were instructed to report every person who had been infected to the department. Consequently, people did not seek treatment from doctors. One would come to know that a family had come into the clutches of the epidemic only when corpses were pulled from the house amidst heart-rendering shrieks.

In those days, I was working as a doctor in the quarantine. Fear of the plague consumed my heart and mind too. In the evening, upon reaching home, I would wash my hands with carbolic soap for a long time; or gargle with an antiseptic potion, or drink hot coffee that would give me indigestion or drink brandy. Because of this, I suffered from sleep deprivation and blinding light in my eyes. On several occasions, I would take emetics to induce vomiting to cleanse my body. Whenever I would get indigestion from drinking very hot coffee or brandy, which caused bouts of hot gas to rise and steam my brain, I would fall prey to all sorts of superstitions just like someone who had lost their wits. If there was the slightest pain in my throat, I’d think, “Oh God! I must have caught the murderous disease… Plague! And then… Quarantine!”

In those days, there was a newly converted Christian named William Bhagu. He was the sweeper who cleaned my street. One day, he came up to me and said, “Sir, it’s strange. Today, about twenty-one have been taken from this area in an ambu.”

“Twenty-one? In an ambulance…?” I asked in shock.

“Yes, sir… Fully twenty and one. They have been taken to the kontine. Will those hapless people ever be able to come back?”

I gathered that Bhagu would get up at three in the morning. After quaffing a small bottle of alcohol, he would spread lime powder in the streets and drains under the committee’s jurisdiction, as instructed, to prevent the microbes from spreading. Bhagu told me that he got up every day at three in the morning to collect the corpses strewn about the bazaar. He also does small chores for those people in the neighborhood where he worked who don’t leave their homes for fear of the disease. Bhagu was not at all afraid of getting the disease. The way he saw it, if death was coming for him, there was nothing he could do to save himself no matter where he was.

In those days, when no one could go near anyone, Bhagu would cover his face and head with his turban cloth and, with great devotion, busy himself helping people. Even though his knowledge was very limited, he could expertly explain to people how to save themselves from the ailment. He instructed them to practice basic hygiene, toss lime powder, and remain inside their homes. One day I saw him counseling people to drink a lot of alcohol. On that day, when he approached me, I asked, “Bhagu, aren’t you afraid of getting the plague?”

“No, sir. Until death comes for me, not even a hair will be askew. You are such a prominent doctor. Thousands have been cured by your hands. But when my time comes, even your medicines will not save me…Sir, I hope you are not offended. I am just saying the plain truth.” Then, to change the subject he asked, “Sir, explain to me what a kontine is… tell me about this kontine.”

“Over there in the quarantine, there are thousands of patients. We treat them to the extent that we can. But how much can we do? The people who work with me are themselves afraid of staying with the patients for a long period of time. Their lips and throats are dry with fear. Unlike you, no one will get close to a patient. Nor will anyone try as hard as you, Bhagu. May God bless you for selfless service to humanity.”

Bhagu bowed his head. Lifting the corner of his scarf and showing me his face, flushed red from drunkenness, he said: “Sir! Of what use am I? I am fortunate if any good comes from my useless body. Sir, L’abe (Reverend Monit L’abe), an important Father who usually comes to my neighborhood to preach, says that the Lord Jesus Christ teaches us to do everything to help the ill… I understand….”

I wanted to appreciate Bhagu’s bravery, but I stopped because I was overwhelmed with emotions. I began to feel jealous upon seeing his faith and practical life. That day, I decided then and there that I would make every effort in the quarantine to keep alive as many patients as possible. I would risk my own life to provide them comfort. But there is a huge gap between saying something and doing it. Upon reaching the quarantine and seeing the patients’ perilous condition, I became overwhelmed by the stench emanating from their mouths. My very soul began to quake, and I was unable to summon the courage to serve them as Bhagu did.

Nonetheless, on that day, I took Bhagu with me and got a lot done in the quarantine. I delegated to Bhagu the varied tasks which required someone to be near a patient; he performed the role without complaint. I remained quite distant from the patients because I was petrified by the thought of death and even more so of the quarantine.

But how is that Bhagu is above both death and the quarantine?

That day, four hundred patients came to the quarantine, and about 250 succumbed to the jaws of death.

I was able to save so many because of Bhagu’s willingness to gamble his own life. There was a graph hanging on the wall of the chief medical officer’s room, which depicted the latest data on patient survival outcomes. It showed that those patients who fared best were those under my care. Every day, I made one excuse or another to take a peek at the chart. It was exhilarating to see that line on its way towards one hundred percent.

One day, I had drunk more brandy than was necessary. My heart began to pound. My pulse started racing like a horse. I began to run around here and there like a madman. I began to worry that perhaps the plague pathogens had finally grabbed hold of me and that soon the lymph nodes in my neck and thighs would begin to swell. I immediately panicked. That day, I wanted to run away from the quarantine. I was shaking the entire time I was there. On that day, I was able to meet Bhagu just twice.

In the afternoon, I saw him embracing some patient. He was patting him lovingly on the hand. The patient mustered as much strength as required to say “Brother, Allah is the king. God would not even bring an enemy to this place. I have two daughters…”

Bhagu interrupted him to say, “Brother, thanks to the Lord Jesus Christ, you look just fine.”

“Yes, brother, by god’s grace… I am much better than I was before. If I could… this quarantine….”

And with that word still on his tongue, his veins bulged. He began frothing at the mouth. His eyes became stones. His body jerked several times, and the patient, who just a moment ago before appeared to everyone –even to himself—to be fine, fell quiet forevermore. Bhagu’s tears seemed as if they were tears of blood. Who else would cry for the dead man? Had any relative been there, they would’ve rendered asunder the earth with their mourning. He only had Bhagu—the relative to everyone. He had pain in his heart for everyone. He cried for everyone and seethed on everyone’s behalf. One day, he humbly offered himself to Lord Jesus Christ in recompense for the sins of mankind.

That day, around evening time, Bhagu ran to see me. He was out of breath. He said in a painful voice, “Sir, this quarantine is hell. Just hell. Father L’abe drew a map of this kind of hell.”

I told him, “Yes, brother, this is even worse than hell. I myself was thinking about making an escape from here. I am feeling very unwell today.”

“Sir, how can hell be worse than this? Today, a patient fainted from fear of the illness. Someone mistaking him for dead tossed him onto a pile of corpses. After dousing the heap with petrol and setting it ablaze, the flames began to consume the corpses. I saw him in the fire, moving his hands and feet. I leapt in and pulled him out. He was so badly burned that my right arm was completely burned while rescuing him.”

I looked at Bhagu’s arm. The yellow fat tissue of his arm was exposed. I was stunned to see him like this. I asked, “In the end, was that man saved?”

“Sir, he was such a noble man. This world could never appreciate his virtuousness and honesty. Even in that state of sheer agony, he lifted up his scorched face, gazed into my eyes with great frailty and thanked me.”

“And sir,” Bhagu said, continuing his story, “then, after so much agony—so much more agony than I have ever witnessed in a dying patient—he passed. It would’ve been so much better had I not saved him from that inferno. By saving him, I kept him alive to bear yet more misery. Even then, he could not be spared. And then I picked him up with my burnt arms and tossed him on the pile.”

After this, Bhagu could say no more. With pangs of pain, he said haltingly, “Do you know… from which disease he died? Not from the plague… From the kontine. From the kontine.”

Even though the idea of hell brought some modicum of solace from the brutality, the sky-rendering shrieks of the terrified patients relentlessly echoed in one’s ears throughout the night. Even though the owls hesitated to hoot, the lamentations of mothers, the screams of sisters, the grieving of wives, and the cries of children could be heard across the neighborhood. If this was a heavy burden upon the chests of those who were safe and sound, how did it demoralize those who were ill in their homes who could see only yellow despair dripping from the doors and windows like a jaundiced person. Then there were those patients of the quarantine who, after crossing all limits of despair, were staring down the king of death. Yet they gripped life as if they were clinging to the top of a tree during a great storm. And as the powerful waves of water kept coming at them, they wanted to take the top of that tree with them when they went under.

That day, I didn’t go to the quarantine either due to my fear of the illness. I made an excuse to do some urgent work. Actually, I was experiencing severe psychological distress…Although it was possible that I could help some patients, the fear which seized my heart and mind also shackled my feet. Late that evening, I received news that some five hundred patients had arrived in the quarantine.

I was about to fall asleep after drinking the scalding coffee, which was still burning in my stomach, when I heard Bhagu’s voice at the door. The servant opened the door, and Bhagu entered panting. He said, “Sir, my wife has fallen ill… her tonsils are swollen… For the love of god, save her… The one and half-year-old child is still nursing. He will die too.”

Instead of mustering even an iota of genuine sympathy, I said angrily “Why didn’t you come sooner? Did the illness begin just now?”

“In the morning, a minor fever… when I went to the kontine…”

“Okay. So, she was sick at home, and yet you still went to the quarantine?”

“Yes, sir. Yes.” Bhagu said, trembling. “It was an ordinary illness. I assumed that perhaps her breasts could not express milk. Apart from this, she had no other problems. And both of my brothers were at home. And there were hundreds of helpless patients in the kontine…”

“You, with your excessive generosity and sacrifice, you brought those germs into your own home. I told you that you should not get so close to the patients… Look, this is the very reason I did not go there today. This is all your fault. Now, what can I do? Heroes like you need to suffer a taste of your own heroism. Wherever there are hundreds of patients piled up in the city…”

Bhagu said beseechingly “But for the sake of Jesus Christ…”

“Go. Leave. Who do you think you are? You deliberately put your hand in the fire. Should I pay the price for your imprudence? Does anything good come from such sacrifices? I can’t help you at all at this hour….”

“But Father L’abe….”

“Leave. Go and see your Father L’abe…”

Bhagu bowed his head and left. Half an hour later, my anger had dissipated, and I regretted my behavior. At least I had enough sense to feel terrible about it afterwards. Without a doubt, my most severe punishment would be trampling upon my pride, begging Bhagu for his forgiveness, and making every conceivable effort to save his wife. I changed my clothes as quickly as possible and ran to Bhagu’s home. Upon arrival, I saw that Bhagu’s younger brothers had laid their sister-in-law on a charpai and were taking her outside….

I asked Bhagu, “Where are they taking her?”

Bhagu said softly, “To the kontine…”

“But don’t you still think the quarantine is a hell, Bhagu?”

“Sir, when you refused to come, what other option was there? I was thinking that we would get the hakeem’s help there, and I could care for her along with the other patients.”

“Put the charpai here… Even now, your brain is still fixated upon other patients…? Fool…”

The bed was taken inside, and I administered to his wife whatever effective medicines I had, and then I began to struggle with my invisible opponent. Bhagu’s wife opened her eyes.

Bhagu said in a trembling voice, “I will never forget your kindness for the rest of my life, sir.”

I said, “Bhagu, I can’t tell you how much I regret how I behaved before… May god repay your service by making your wife healthy.”

In that moment, I saw my invisible foe deploy his last weapon. Bhagu’s wife’s lips began to tremble. Her pulse, which had slowed in my hand, continued to weaken. My invisible enemy, who is regularly victorious, knocked me down on all fours as usual. I lowered my head remorsefully and said, “Bhagu, ill-fated Bhagu! This is a peculiar reward for all of your sacrifices.”

Bhagu burst into tears. It was difficult to watch as he removed his crying child from his mother and humbly asked me to leave. I had thought that Bhagu, having accepted the darkness of his own life, would no longer care for others…. But the very next day, I saw him helping even more patients than before. He saved the lights of hundreds of homes… And he paid absolutely no heed to his own life. Even I followed Bhagu’s example and began working with enthusiasm. In my spare time—when I was free from my work in the quarantine and hospital—I turned my attention to the homes of the city’s poor, which are epicenters due to their proximity to sewers or filth.

Now, the atmosphere is completely free of the pathogen that caused the illness. The entire city has been cleansed. There are no signs of rats. In the entire city, there are but a few cases of the disease which, after getting immediate attention, do not spread further.

Throughout the city, business returned to normal. Schools, colleges, and offices began to reopen.

One thing I felt for certain was that people were pointing at me from every direction as I passed through the bazaar. People looked upon me with grateful eyes. My picture was published in the newspaper along with flattering words. I began to feel pretty arrogant after receiving so much praise and compliments wherever I went.

Ultimately, there was a large ceremony to which all of the city’s well-heeled citizens and doctors were invited. The Minister of the Municipality presided over it. I was seated next to the minister because this program had, in fact, been organized in my honor. My neck strained under the weight of the garlands. Feeling honored and looking about, the committee was giving me a token sum of one thousand rupees as recompense for my diligent work on behalf of humanity.

All of the people who were there praised my colleagues generally and me, in particular, and exclaimed that the number of lives that were saved during the plague due to my diligence and dedication were innumerable. I couldn’t tell you whether it was day or night. I believed that my life was tantamount to the life of the nation and my wealth to be the treasure of society. I entered the homes of the ill and gave the dying patients the elixir of health!

The Minister of the Municipality stood on the left side and picked up a walking stick. Addressing the audience, he used his stick to draw their attention to a black line on the chart, which was hanging on the wall. The line depicted how, throughout the course of the epidemic, the health of the public continuously improved at every moment during the crisis. He concluded by referencing the chart, which also indicated the day when fifty-four patients were remanded to my care, all of whom recovered. In other words, my success rate was one hundred per cent, and the black line reached its zenith.

After this, the minister acknowledged my courage in his speech and said that the people would be pleased to know that Bakhshi was being promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in acknowledgment of his service. The hall was filled with the thunderous sound of loud applause.

During the ovation, I raised my head in pride. I thanked the dignitaries and distinguished audience in a lengthy oration. In addition, I also explained that doctors did not just devote their attention to the hospitals and quarantines but also to the homes of the impoverished. Those people had no one to help them, and they generally succumbed to this fatal disease. My colleagues and I searched for—and found—the epicenter of the illness and focused our attention upon eradicating the disease at its source. After finishing up our work in the hospital and quarantine, we would spend the night in those dreadful houses.

That same day, after the ceremony, with my rank of lieutenant colonel, I held my head high with pride, laden with garlands and one thousand rupees—a token gift from the people–stuffed in my pocket. Upon reaching home, I heard a soft voice off to the side.

“Babu Ji… So many congratulations to you!”

And Bhagu, while congratulating me, placed that same old broom on the lid of a filthy, nearby cistern and, with both hands, removed the cloth he had tied around his face. I was startled.

“Is that you?… Bhagu brother!” I barely managed to say… “The world doesn’t know you, Bhagu, and even if it never does, I know you. And I know your Jesus.…L’abe’s great disciple… May god bless you.” At that time, my throat became dry. The image of Bhagu’s dying wife and child flashed before my eyes. My neck felt as if it was snapping from the heft of the garlands, and my pocket was bursting at the seams from the weight of my wallet and. Despite receiving all of these honors, I began to mourn this world that had so much appreciation for a worthless man.

***

About the Translator:

C. Christine Fair is a professor in Georgetown University’s Security Studies Program within the School of Foreign Service. She studies political and military events of South Asia and travels extensively throughout Asia and the Middle East. Her books include In Their Own Words: Understanding the Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (OUP 2019); Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (OUP, 2014); and Cuisines of the Axis of Evil and Other Irritating States (Globe Pequot, 2008). Her forthcoming book is Lines of Control: Lashkar-e-Tayyaba’s Militant Piety, with Safina Ustad (Oxford University Press, 2021). She has published creative pieces in The Bark, The Dime Show Review, Furious Gazelle, Hyptertext, Lunch Ticket, Clementine Unbound, Fifty Word Stories, The Drabble, Sandy River Review, Barzakh Magazine, Bluntly Magazine, Badlands Literary Journal, among others. Her visual work has appeared in Vox Populi, pulpMAG, The Indianapolis Review, Typehouse Literary Magazine, The New Southern Fugitives, Glassworks and Existere Journal of Arts. Her translations have appeared in the Bombay Literary Magazine and Bombay Review. She causes trouble in multiple languages.