“I am very sorry that our actors should learn acting from England or America. Our acting must be Indian and must come from within,” said Himanshu Rai, the owner of the powerful Bombay Talkies – a studio that produced some of the most relevant, famous, and successful films of the 30s and 40s – more than a decade before Independence. These films signal the ethos for an art form that remains pertinent to other art forms – scripting, direction, music, and of course, the less delved upon – the film publicity art.

Considering that cinema, since its advent in India, was not a very “acceptable” phenomenon in society, its form and content, deliberately so, were kept mostly within the socio-religious circle by the producers. The dearth of female performers had men dressing up as women in the pre-20s theatre and silent films. The “family” audience for cinema was skeptical and reluctant for two reasons – the Hollywood “bold” culture of the screened foreign films shocked the conservative Indian society, and secondly, the medium itself was looked at as a threat to Indian culture.

The producers, therefore, focused on the “acceptability factor.” If one looks at the themes that dominated Indian cinema in the silent and early talkie films, we see less of contemporary issues, themes, topical stories, and more of mythology and folklore. The reason is the effort to bring in the “family” audience through the themes of religion and folklore so that the stigma on cinema as “an alien art-form out to dilute our culture” gets erased. This worked, though slowly, as India moved towards independence. The earliest film posters were not just influenced by mythological calendar art; they emerged out of the same art form since most of the early designers were well-known painters themselves.

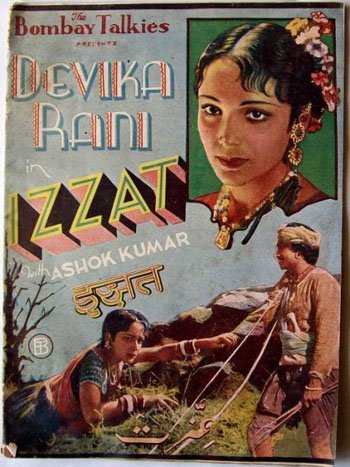

A classic case in point is that of the legendary Baburao Painter, V Shantaram’s mentor, whose posters have often been compared with the style of Raja Ravi Varma. As we move from the 30s to the 40s, we see very basic traditional poster art on display, having transitioned from the mythology lithographic prints to larger format film posters from the same press. The color palettes, the look and feel of the final prints, revolved around earthy organic colors to depict the film themes.

Interestingly, the heroines were usually the central figures and bigger stars across the 30s and most of the 40s. This is very clear if one looks at the film publicity artworks of the era. Devika Rani dwarfed Ashok Kumar in their Bombay Talkies classics, Sulochana towered over her Imperial Cinetone heroes like the Billimoria brothers, Gohar led the cast of Ranjit Movietone classics, Fearless Nadia had mostly solo posters of her action flicks! Not that the men were any less heroic, but the adulation for the heroine was obviously more pronounced; therefore, commerce dictated the publicity.

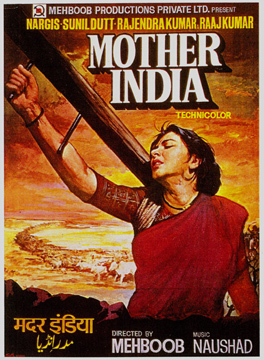

As India attained independence, many changes were seen in the film industry. The traditional studios which controlled most of the industry began to struggle against the new format of owner-based production companies. For example, V Shantaram left Prabhat Studios and formed Raj Kamal Kalamandir, Ashok Kumar left Bombay Talkies. Ranjit Movietone, New Theatres and Minerva Movietone ran in losses, and entities like Mehboob Studios, RK Studios, Navketan, Sippy Films, B R Films established themselves.

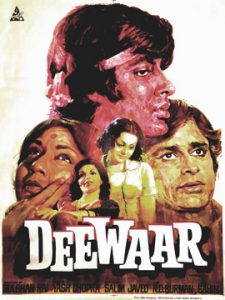

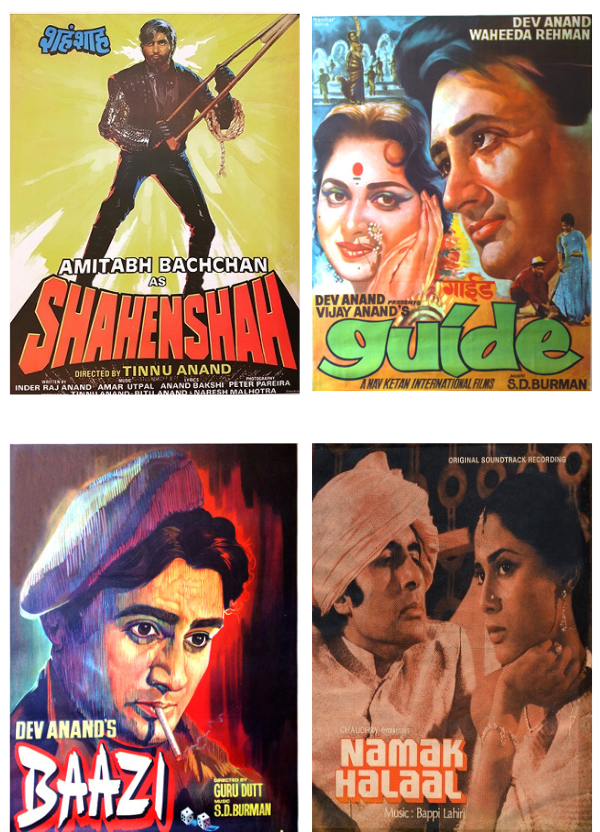

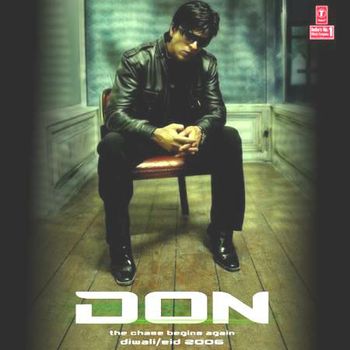

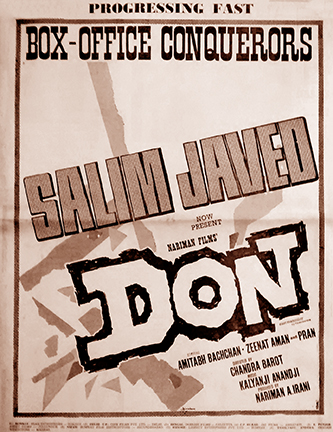

The tide began to turn in favor of the hero. Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand rose in popularity, and the hero became the primary attraction on the film poster. Later in the 70s, the angry young man and the gun replaced romance on the billboards as Amitabh Bachchan ruled the box office for two decades. The lithographic press stayed on till the late 80s, and the calendar art designers continued to hold sway, primarily S M Pandit, Pandit Ramkumar Sharma, followed by J P Singhal, Tilak and Prithvi Soni in the later decades. When we reach the 90s with Aashiqui, Hum Apke Hain Kaun and Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, romance staged a spectacular comeback on the posters. However, the expressionism of the paintbrush was lost. Since the turn of the millennium, digitally designed film publicity has taken over, writing over the soul of hand-designed art.

Film Publicity has evolved with time, transcending technological advancements of both designing and printing, as we move from post-independence India towards the current times, and the following media deserve a look:

THE POSTER

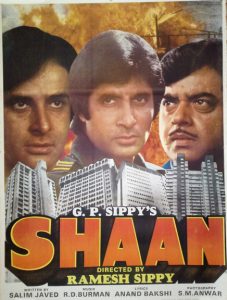

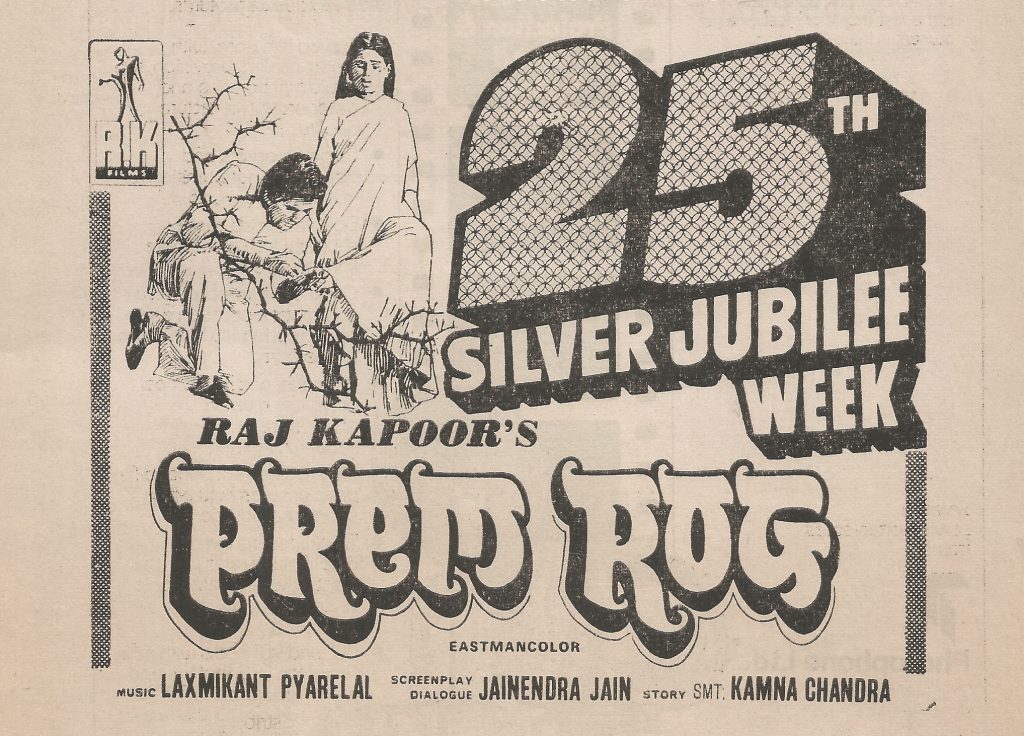

Heart and soul of film publicity, the posters have three essential sizes – the half sheet (20×30 inches), the full sheet (30×40 inches) and the 6 sheet (where 6 posters add up to 120×60 inch dimensions). Initially, the lithographic press created posters right across the 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s. Star designers like C Mohan, Diwakar Karkare and D R Bhosle designed some of the finest posters in these decades. From the 80s onwards, there was a transition to the off-set press. It reduced the use of hand designs, photographs of stars appeared directly on posters against the background design. (case in point – Ramesh Sippy’s Shaan and Muzaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan). By the turn of the millennium, we saw the digital press in wide use and designing being done on computer-generated applications, which continues till date.

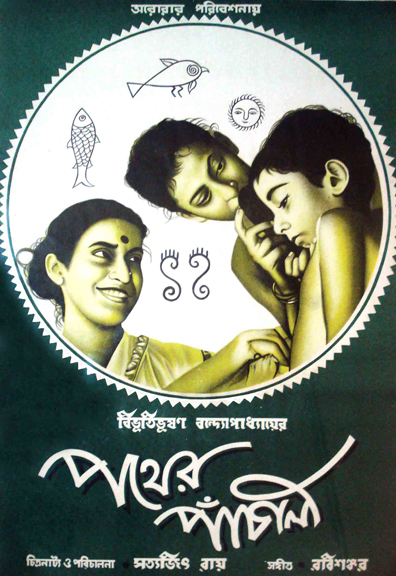

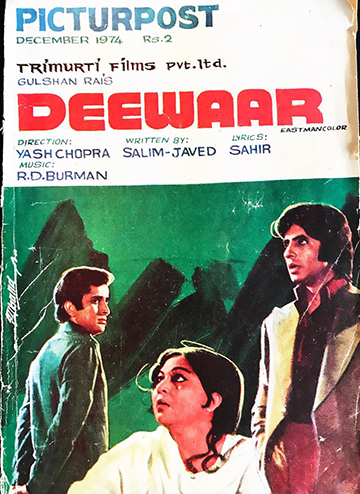

However, the hand-designed art of the lithographic press posters has belatedly attracted the fascinated attention of the art aficionado and the film fan alike. Consequently, original first-release film posters of classics and those featuring top stars, or even those of the award-winning parallel cinema, are finding their way in auctions, farm-house lobbies and even living rooms. The prices for these posters are increasing because of the limited access to first-release posters. Therefore, if you are lucky enough to own a poster of Pather Panchali, Deewaar, or Aandhi, you have many reasons to cherish your possession!

LOBBY CARDS AND SHOW CARDS

Lobby Cards and Show Cards were usually displayed in the foyer or lobbies of the theatres showing the film. Lobby Cards are usually original large-size photos bearing the film’s name/logo and some basic credits. Sometimes the same photo/photo collages are mounted on cardboards. These are usually in sets of 10/12. From the 40s till the 60s, lobby cards were typically black and white, unless hand colored for some special films. From the 70s onwards, these lobby cards were color stills mounted on cardboards. Post the new millennium, lobby cards were directly printed on digital press on thick glossy paper.

The Show Card was creatively more elaborate. It was either a standalone artwork of the film’s poster or its litho/offset print mounted on a card, where photographs were uniquely used along with the art on the board to create an attractive poster.

FILM JOURNALS

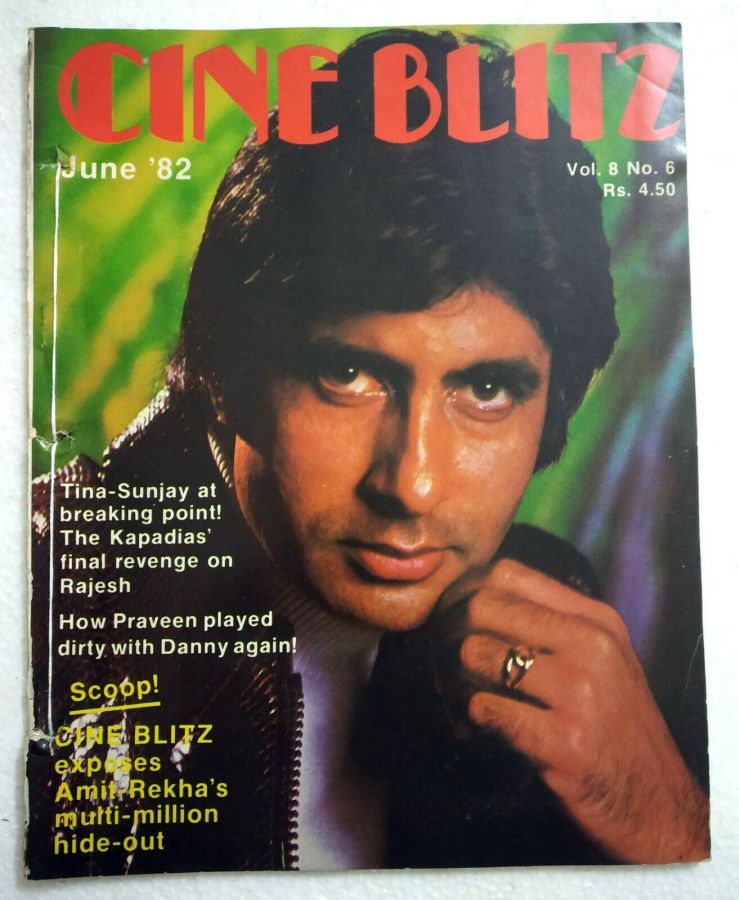

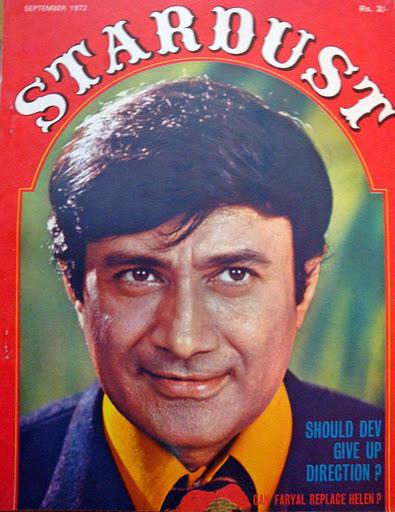

The art of film publicity was always uniquely presented in film magazines and journals. Post-1947, Film India was the most popular and expensive film monthly till the arrival of Filmfare on March 7, 1952 with the first cover of Kamini Kaushal. Later on, several successful magazines mushroomed, viz. Star&Style, Madhuri, G, Shama/Sushma, Picturpost, Stardust, Cine Blitz, Movie, Mayapuri, Chitralekha etc. However, in Film India, Shama/Sushma, Picturpost and Mother India, the cover of the magazine was almost always a film poster designed by the in-house art department of the respective journal. Consequently, the value of these magazines for a film fan is unique for the sheer visuals. And then, trade journals like Trade Guide and Film Information were primarily circulated within the film fraternity and its distribution partners. Among newspapers, Screen has been most popular, followed by Cine Advance and The Film Industry journal. However, the most memorable element of newspapers is the unique teaser ads of big-budget films and the multiple ads for new releases that were mostly black and white poster designs till the late 80s.

OUTDOOR PUBLICITY

Innovative ways to publicize a film endeared the film fans to the outdoor publicity media. Rickshaws and Tongas displaying posters and playing vinyl records on battery-operated record players were common in the 50s, 60s and 70s. The publicity for Mughal-e-Azam went beyond normal levels – regally decorated elephants were hired in several metros to herald the arrival of the film. Then, there were sensational large outdoor hoardings, essentially enlarged posters hand-painted by the grid method. Specific crossings and city areas were assigned to such hoardings for the big-budget extravaganzas. As the hoardings were put up, there used to be crowds cheering the process. Theatre exteriors also had elaborate cutouts, and the hero was usually garlanded as the film opened!

LP RECORDS

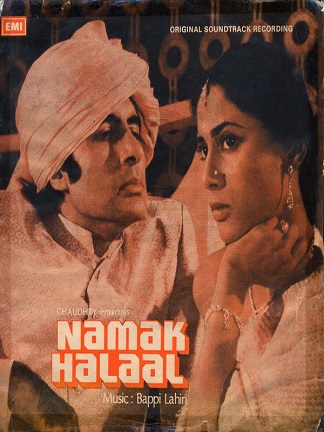

Music has always been an essential element of Indian cinema. When India became independent, it was the era of 78 RPM records, on which film music was popular. It was only with Mehboob Khan’s 1957 classic Mother India that vinyl LPs were introduced and became a part of every festivity in the country. Polydor issued the first dialogue LP set for G P Sippy’s 1975 monster hit Sholay, and it’s only after its extraordinary success that HMV released the Mughal-e-Azam dialogue LP. LPs were always black, therefore; it was a unique experiment by Polydor to bring out India’s first ‘Red’ LP for Manmohan Desai’s 1977 blockbuster Amar Akbar Anthony. The transition from LPs to audio cassettes happened largely in the 80s. The first film audio cassette to hit the market was however, Gulshan Rai’s Trishul (1978). From audio cassettes, the film music passed on to the CD in the 90s, Subhash Ghai’s Ram Lakhan (1989) being the first film to issue its soundtrack on audio CD. With the turn of the millennium, music is mainly online, with specific music now getting segregated to the apps.

THE FILM BOOKLET/BROCHURE/HANDBILL

The humble film booklet is the single most important source of information on each film. Within a booklet of barely 7/8 pages, you get the film’s original poster in miniature form, its credits, synopsis and all the songs! The tradition of the film booklet began in the silent era, and it actually branched out of the Parsi/Marathi/Gujarati theatre tradition of the early 19th century. Booklets are now the source for crucial details about several film posters lost forever as prints. Though booklets have been discontinued in the last few years, as most information on the new releases is already handy online, the booklet is the most important element of film publicity for information, documentation and archival.

Post-independence, Indian cinema has seen myriad transitions in its film publicity options. Though it’s not possible to dwell in detail on each innovative stream, there is also a role of the merchandise – there were thermos flasks of famous films, compact fans, postcards, playing cards, key chains, diaries, calendars which have aided in publicizing a film.