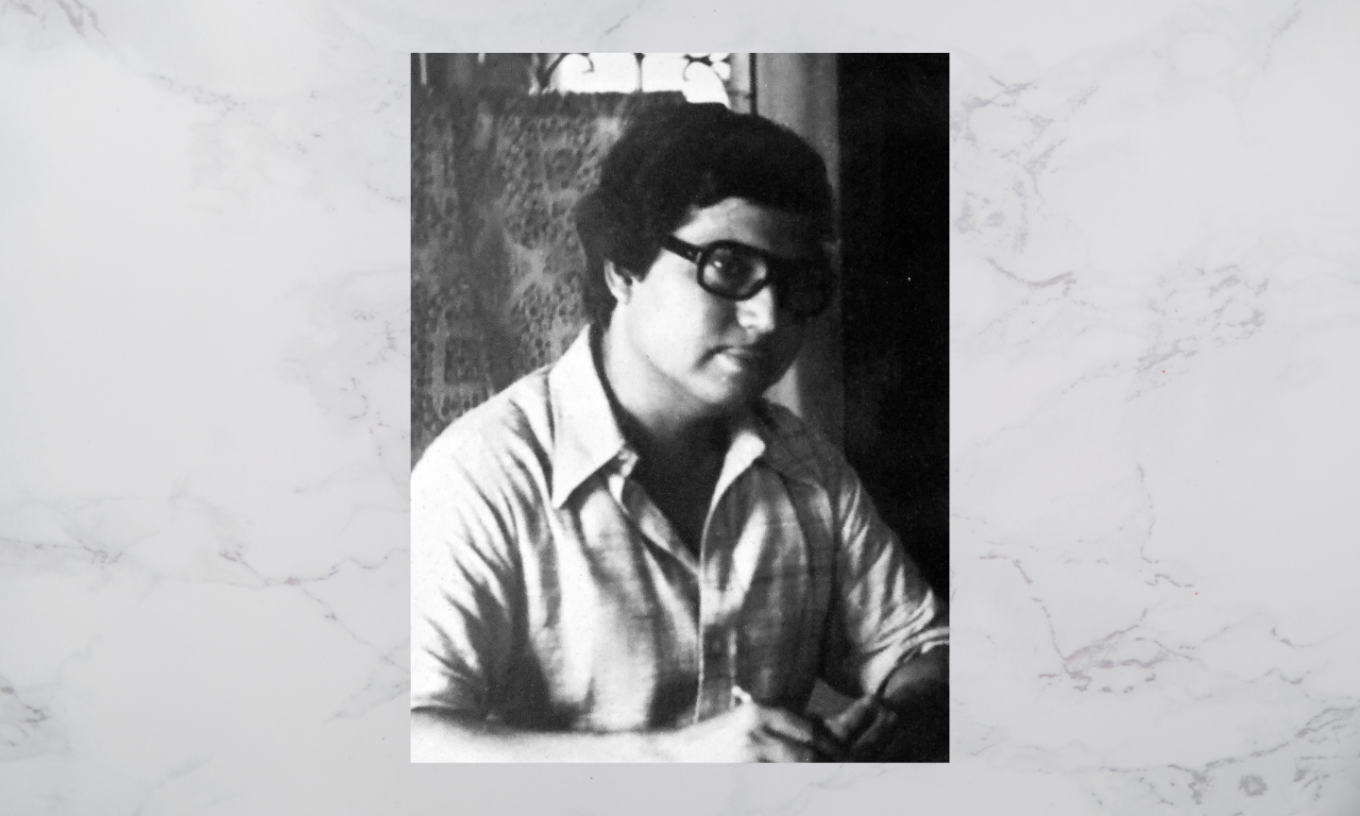

After the 1940s, it is only in the 1960s that we see a certain kind of social commitment and political involvement making a return to Bangla poetry. Robin Sur, Pabitra Guha, Basudev Deb, Ananda Ghosh Hajra, Ananta Das, Rabindra Guha and others form a core group of such poets. Monibhushan was foremost amongst them, though he cannot be confined only within this lineage or time frame. This thread runs along the Hungryalist and the Shruti schools, and traipses past the anti-poetry movement or other, more inward-looking trends. For Monibhushan, life is an uncompromising engagement with our ignominy, struggle and anger arising thereof. But most importantly: a ruthless introspection.

Compositor

The name that appears in print as the publisher

That is not you.

Because the one who owns land is the tiller

Not the one who tills.

The one who makes, chisels, constructs or produces is the

Shramik;

The one who supplies money is the producer.

The one who writes is not the writer

One whose books sell more is the writer

Therefore, you are not the publisher

You are the compositor.

From 1965-1971, Monibhushan composed twenty-one sonnets: with a leitmotif of ‘Swan’ in mind. By 2007, fifty-one new sonnets were written on the same theme and an independent book with the title Swan came into being in 2011. Seventy-two sonnets altogether. The working out of the motif is startlingly different from Yeats’, Rilke’s or in Tchaikovsky’s handling of similar material from Russian folktale. In this case, the Swan is a surrogate for the full canvas of poetry in actuality, which in a manner is also his beloved. A highly charged quantum of intensity suffuses this series; a classical form of modernity which later would meander into a more pronounced people’s poetry.

From the Swan poems:

I shall keep you in my heart to free you into the flower

Then pluck you, twisting-strangling your divine neck

When your twin lips swell with clotted blood, I shall clap

Strewing feathers, scattering you adjacent, most close

Smashing the closer ribs, shall draw you even closer, you

Cannot pluck high-afternoons from another’s lake

The lake shall surge with a heap of strewn feathers

All of the day, my drumming of sun’s dundubhi with you

Elegy (not too many in Bangla) is originally a genre of mood, not a mode. It could turn quickly into a song of lamentation, in particular a funeral song or lament for the dead. Monibhushan writes a short elegy after the death of a great working-class leader, turning it into a fearful apocalyptic vision for the multitude. But such is the restraint of the poet, such his economy of expression, that it will be impossible to turn such a spectacular vision into a spectacle. It will be impossible to construct a mere nostalgic consumptive imagery of the leader’s death after such a vision.

There is not a sound in the sky

Not a sound in the water

No sound above or below the skin

In the mountains, mines, heart, no sound nowhere

Every branch and bough turned to blackened stone

Only a single sun-craving crane

Firm austerity in the heart

By the thrashing of his wings

Quashing, effacing the filthy amassing

Of pathetic convulsions all around him

Up and above, blazing, smouldering

Though the lead-filled midnight’s murdering

In a pristine fire-line

Fades into the horizon, and

Once upon another, and another

At the hammers pounding

A brumming, rhythmic clanging rings in

Endless brassy nights.

*These poems and text excerpted with kind permission from Prashanta Chakravarty’s essay, That Sun-Craving Crane, published in The Opulence of Existence- Essays on Aesthetics and Politics. The writer wishes to acknowledge that inputs and ideas for the translations presented here are from Monibhushan’s own writing as well as that of his partner Alo Bhattacharya’s book, Kobi Manibhushan.