- Study English and Migrate/Migrate and Study English

A parasite is by its very nature a wanderer, an alien, a migrant – a creature who does not belong in a habitat of its own but which pretends to belong through imitation or mimicry. It is no surprise then that narratives of parasitism are obsessed with the English language; it is through English that the parasite can enter spaces otherwise closed to it. Example A: the critically acclaimed, Academy Award-winning Parasite (2019) begins with Kim Ki-woo forging university credentials in order to be an English tutor to the daughter of the rich Park family. Once safely installed in their obscenely beautiful and modern mansion, Ki-woo helps his family get jobs in the house as well, his father as the driver, his mother as the housekeeper, and his sister as an art therapist for Da-Song, the Parks’ traumatized little toddler who seems to have an artistic bent. But it all starts with English. English opens doors to underpaid wage labor for the Kims, but it will also open doors for Park Da-hye, Ki-woo’s student. She will be able to attend college in America and maintain her class status. English enables different modes of parasitism for both families.

But representing English as a talisman capable of transporting a parasite across borders and boundaries has a longer history. Example B: this semester I taught Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). As one of the protagonists and future victims of Count Dracula, Jonathan Harker, explores the vampiric Count’s castle, he comes across a library with “a vast number of English books, whole shelves full of them, and bound volumes of magazines and newspapers. A table in the centre was littered with English magazines and newspapers, though none of them were of very recent date. The books were of the most varied kind, history, geography, politics, political economy, botany, geology, law, all relating to England and English life and customs and manners.” Like Ki-woo, Dracula must refashion himself through learning and imitation, if not outright forgery. Ki-woo needed to cross the boundary into the Park family’s home; Dracula is preparing for his eventual migration to England, as he tells Jonathan: “I long to go through the crowded streets of your mighty London, to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life, its change, its death, and all that makes it what it is. But alas! As yet I only know your tongue through books. To you, my friend, I look that I know it to speak.” In the recent Netflix mini-series adaptation (2020) of the novel, Claes Bang’s seductively portrayed Dracula suggests that he will literally “absorb” the correct English intonation from Jonathan. Learning English is in itself a parasitic act, but teaching it is more so.

***

“You’re from Pakistan? But your English is outstanding!”

***

Example C: in E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924), the cholera epidemic is inextricably entwined with the British colonial education system in India. In Chapter IX, the native Indian physician Dr. Aziz falls slightly ill after attending a tea party held by the principal of the Government College, Cyril Fielding. Dr. Aziz’s friends visit to inquire about his health and, after learning that their mutual friend Professor Godbole has also fallen ill, facetiously wonder if Fielding tried to poison them. Rafi, the nephew of one of Aziz’s friends, avers that Godbole has cholera. However, it is later revealed that it is just hemorrhoids. Everyone chides Rafi for spreading rumors, and Aziz says: “I hear cholera, I hear bubonic plague, I hear every species of lie. Where will it end, I ask myself sometimes. This city is full of misstatements, and the originators of them ought to be discovered and punished authorit- atively.” When asked why he spread this bit of misinformation, Rafi blames it on the education system, which Principal Fielding represents: “The schoolboy murmured that another boy had told him, also that the bad English grammar the Government obliged them to use often gave the wrong meaning for words, and so led scholars to mistakes.” Thus, even if Fielding didn’t poison his guests, he becomes implicated in an English education system that, through its flawed grammatical pedagogy, inadvertently spreads a lie: cholera parasites are at large.

But what we usually don’t recognize is that colonizers like Cyril Fielding were the first parasitic immigrants, trying to conjure a mini-England in the outposts of their Empire – and teaching the natives English was central to that endeavor. As literary critic Gauri Viswanathan has argued in Masks of Conquest (1989), the establishment of “English literature” as a discipline in India was vital for the operation of colonial control and to manufacture consent from the colonized. The narrative of the non-English-speaking immigrant is more familiar to us, but not that of the English-teaching immigrant of the colonial era.

***

That is why my English is so outstanding. Pakistan has two official languages: Urdu and English. But unlike other immigrants who must overcome the language barrier before or after moving to the new country, I came here and decided to pursue doctoral studies in English literature. I am a Pakistani-American Cyril Fielding, except I will always be legible as a Dr. Aziz. Or a “Mr. Patel,” as one white student referred to me in his weekly writing assignment.

When I migrated, I knew the language but had to discipline my tongue to mimic the looser, more vulgar intonations of the American accent. Eventually, like Dracula, that specter of reverse-colonization, I absorbed it.

***

A primal scene of English language instruction in the post-colony. Circa 1996, Karachi, pre-K. I find a feather on the playground and bring it to the teacher who usually beats and verbally abuses me: “F for Feather!” I exclaim – maybe that will make her like me more. I only now have more choice vocabulary for that specific letter and for that teacher. In any event, the feather gave me wings and I flew away.

- Get Sick, Be Driven Out by Host/Be Driven Out by Host, Get Sick

Back to Example A. In Parasite, in order to get their mother the housekeeper’s job, the Kim family gets rid of the old housekeeper Gook Moon-gwang by making it look like she has tuberculosis. Through their expertly choreographed espionage, they discover that Gook is lethally allergic to peaches, a fruit which has therefore been banned from the Park mansion. But the Kims find a way around it – they smuggle in the fibrous tissue found on the skin of the peaches and sprinkle it gingerly over poor Gook, who reacts with a violent, racking cough. For added believability, as Gook disposes of her snotty tissues into the trash can, Mr. Kim pours a generous serving of hot sauce on the tissues and shows them to Mrs. Park, who now believes beyond a reasonable doubt that Goon has TB. Goon is promptly let go, without getting a chance to even see her husband who has been living in the bunker beneath the basement of the mansion. (The bunker was apparently included by the architect in case of a nuclear attack by North Korea). Only Gook knows about the bunker – the Parks have been living with a parasite right beneath their feet.

***

As a parasite, I too have lived in a basement, if not a bunker, hearing the footsteps of my generous benefactors clack on the ceiling on wintry Michigan mornings. I migrated to the United States in August 2010, courtesy of my maternal uncle who sponsored my mother and her family’s immigration back in the 90s. My mother, sister, and I were promised sanctuary for one year in the basement of my uncle’s house in Kalamazoo. But the tolerance of our hosts ran out midway: mostly, because I think my aunt could not stand the fact that my mother was not working but only there to support us. She had money coming in from Pakistan — she didn’t need to work. This made her a parasite. But like Mr. Park from Parasite, our hosts were also all too cautious for certain lines to not be crossed. It was inappropriate for my sister and I to study for our SATs in the dining room upstairs. My mother must not cook in the kitchen upstairs either, unless my aunt had commanded her to make a particular dish for expected guests. But boundaries could be crossed in other ways: their son spent too much time in the basement with us, eating our snacks. His mother was worried, I think, that he would get too attached to us. He stopped coming down altogether, except to tell us one day that I was using up too much ink from the printer: pay up for ink or buy your own. I told Mom: she started crying. I thought we were family; family doesn’t ask family for money. We bought our own printer. The sounds of Aunt and Uncle fighting upstairs: I don’t want them in the house. We packed the boxes again, found a two-bedroom apartment and moved there on a snowy Christmas Day.

***

In his book Contagious Divides (2001), historian Nayan Shah shows that in the 1910s, with the establishment of both the Angel Island Quarantine Station and the Angel Island Immigration Station, South Asian immigrants to the West Coast of the United States were detained and subjected to bacteriological examinations, particularly to check for hookworm, the proverbial “germ of laziness.” The new fields of bacteriology and parasitology had confirmed the theory of the “healthy carrier,” a person who harbors parasites in her body but who may not show external signs or symptoms. The fecal matter of these Asian Indians was microscopically examined for hookworm eggs and subjected to curative experiments. But more interestingly, the Indian immigrants’ abject poverty was understood as proof of their laziness, itself a side-effect of their intestinal parasites. Thus, the figure of the social parasite — the lazy, disabled immigrant who refuses to work and becomes a drain on government resources — was conflated and collapsed with the biological parasites which infected him.

***

My metamorphosis into a parasite of the American social body was actually enabled by the enduring legacy of British colonial culture. My family inherited their traditions: keep a chauffeur, an army of maids, a cook. We were already parasites on the labor of Pakistan’s rural poor. I didn’t learn to drive until I was 25 — American individualism hit me like a slap in the face. Finishing my senior year of high school in Kalamazoo, I relied on the goodwill of my fellow classmates to give me rides to and from school, but also to and from research. I worked as a research assistant in an antibody engineering lab at Pfizer Animal Health, where I would go twice a week after school with a friend who worked for another lab there – she would drive us to and from the Math and Science magnet school which sought out mentors in the scientific community for their students. Dr. Bergeron was assigned to me as a mentor and she helped me devise a project, the logic of which I never really understood. It had something to do with demonstrating how the potency of certain antibodies could be increased. It involved lots of benchwork; pipettes, centrifuges, agar plates, DNA gels. But I found the entire thing tedious. I could not stand at the bench for hours on end — fatigue and shortness of breath would overtake me. My hands shook as I held onto the pipette. It was the beginning of the end of my short-lived scientific career.

I marveled at my American classmates like Alexandra, the friend who also worked at Pfizer and drove me there. I was in awe of their able-bodiedness and their able-mindedness: they did so much in a day. Schoolwork, sports, research, volunteering. I, on the other hand, was lazy.

***

Dr. Bergeron and Alexandra’s mentor visited me in the hospital when they found out I had been diagnosed with leukemia. It was small consolation to me that my failures in Bergeron’s lab were probably due to the disease. At some points, when I would wallow in self-pity and ask why me? I even suspected that the research is what caused the cancer. After all, I was exposed to all kinds of chemicals and radiation. But it didn’t matter what caused it. There was no way to know.

In any event, I signed on to the standard arm of the treatment regimen for leukemia in boys. The first phase was called “induction,” in which they completely bombarded my immune system with chemo. As a result, I became “neutropenic” and at high risk of infection. Everyone around me had to wear masks and use hand sanitizer. But all those precautionary measures failed, because I soon underwent a septic shock and was afflicted with a pernicious form of pneumonia caused by the fungus Candida albicans, which lives in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth of most healthy adults. However, in immunocompromised patients the fungus can cause pneumonia, and the mortality rate of the infection can be as high as 90%. My healthcare team put me on a cocktail of antibiotics because they first assumed that the infection was bacterial. The pneumonia persisted, until one day I coughed up a large chunk of sputum from the wall of my right lung which finally revealed that what I had was in fact a fungal infection. I responded well to the anti-fungals such as fluconazole.

But a consequence of the antibiotics was another infection: Clostridioides difficile, or C-Diff. The human gut is home to lots of “good” bacteria which fight off opportunistic infections, but they can be killed by an overuse of antibiotics, allowing the “bad” bacteria like C-Diff to take over. That is precisely what happens with C-Diff, which produces nausea, fever, abdominal pain, and intense diarrhea described as having a “sickeningly sweet” smell. The scientists first named the germ in 1935, choosing the appellation difficil, Latin for difficult, because the bacterium grows very slowly in culture. But it might as well refer to the difficulty of managing its symptoms. For three months I was infected with both fungal pneumonia and C-Diff, so that I would be coughing up blood on the one hand and shitting blood on the other. There would be times when I tried to lie down as still as possible on my hospital bed, because even a slight movement would lead to coughing and diarrhea. I feared standing at the sink for too long while brushing my teeth, for fear that an attack of diarrhea would soil me. I lay in bed for three months, prisoner to the parasites of my body. I still bear bedsores on my back as evidence, but also less tangible proofs. I still feel irrationally irritated by, or rather am incapable of, standing at the sink for more than two minutes while doing my morning toilette.

- Be the Third

“A third arrives who has no relation to the people or the things but who only relates to their relation. He branches onto the channel. He intercepts the relation. He is not mediation but an intermediary. He is not necessarily useful, except of course for his own survival : this relation to the relation allows him to exist. But the danger he is in is immediately visible: he can be excluded by an association grouping the two subjects whose relation he parasites, or by one subject who wants to keep the object exclusively for himself. This risk of exclusion is known to him as soon as he sits down at the table , as soon as he is hungry. A risk of death.” – Michel Serres, The Parasite (1982)

I write this section of the essay while in self-isolation at my sister’s place in Toledo, where she is a medical student. A viral parasite is at large: the COVID-19 pandemic rages beyond the walls. I will be moving here in April when my lease runs out in Ann Arbor. Both my and my sister’s universities have switched to virtual learning. I am the third human being here, besides my mother and sister (Leo the Cat does not count). I was the third in my living situation in Ann Arbor. I am the third and youngest (and probably accidental) child in my family.

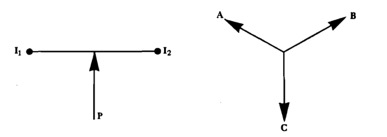

The French philosopher Michel Serres recognized the inevitable “thirdness” of parasitism. The third is a parasite of the relation between the first two. Its survival depends on that relation, but once the parasite enters into relation, the mechanics of the system change, so that any one of the three can be a parasite: the thirdness of the parasite is contagious. Serres illustrates the concept in the following diagram:

Back to Example A: Parasite (2019) follows three nuclear families: the Kims, the Parks, and the housekeeper Gook Moon-gwang and her husband. In the beginning of the film it is clear that the Kims are the parasites in the relation between the Parks and their wealth, but by the end of the film it is difficult to call just one of the families the titular parasite. The rich Parks are parasitic on the labor of the Kims and Gook; the Kims are parasitic on Gook by conspiring to have her let go; Gook’s husband is parasitic on both the Parks and the Kims as he continues his life in the bunker under the mansion as a fugitive from debt collectors (parasites themselves). The third is the unwanted, the migrant, the wanderer. The parasite.

In July of last year I moved into a beautiful three-bedroom apartment in the Old West Side of Ann Arbor. Two of my friends in the department had found the place and were looking for a third roommate, and I happily signed on to escape my windowless room in university housing where I had lived for two years. In the fall of that year I also started teaching English for a specialized health scholars program for freshmen at the university, and my course explored representations of infectious disease in literature. We had modules on plague, cholera, TB, malaria, Hansen’s disease (leprosy), and HIV/AIDS. As it happens in English classes, art imitates life and vice versa, but this time I got to experience that uncanniness as a teacher, not as a student.

The plague module, with readings from Boccaccio’s Decameron, Camus’ The Plague, and Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, intersected with a flea infestation in our apartment. We don’t know how it started, but one of my roommates had taken in a friend’s dog for a week while her friend was away for a wedding. She (the dog) might have made it worse, or brought in the fleas in the first place. But my room became the epicenter, and the infestation soon spread to the entire house.

The bites, mainly on the feet and legs, appeared as small red bumps and were excruciatingly itchy. The infestation made us experts in (mostly ineffective) home remedies to control the outbreak: for instance, putting Borax and salt under the rugs and in nooks and crannies of the house, or setting up a flea trap in each of our rooms. The latter worked better than the former. It involved mixing water and soap in a medium-sized bowl and placing the bowl under a lamp while keeping the room relatively cool, the logic being that fleas are attracted to warmth. And sure enough, the fleas, like Icarus, would jump too close to the lightbulb, fall into the soapy water, and drown. Like Defoe’s narrator in Journal of the Plague Year, who tallied the daily deaths in London during the plague of 1665, we counted the number of drowned fleas every morning. The highest count in my room was 6, but our efforts were eventually futile. We had to bring in the big guns. The exterminators were called in and we fled the home for a week.

***

“But history hides the fact that man is the universal parasite, that everything and everyone around him is a hospitable space. Plants and animals are always his hosts; man is always necessarily their guest. Always taking, never giving. He bends the logic of exchange and of giving in his favor when he is dealing with nature as a whole. When he is dealing with his kind, he continues to do so; he wants to be the parasite of man as well. And his kind want to be so too. Hence rivalry.” – Michel Serres, The Parasite

***

The fleas were finally gone and we returned to the apartment. But those entomological parasites were replaced by a human one: me. I was dirty and lazy. I never cleaned up after myself in the bathroom or the kitchen – I think it was because those two places had sinks. I could not stand, literally, having to clean up after myself. I don’t mean to use my experiences at the hospital sink as an excuse. Or maybe I do. And so there were times when the sinks collected my hair and my used plates. I ate one of my roommates’ ice creams in the freezer, like a true parasite. I treated the house like my own property and had a student-group meeting without first telling my roommates. Chaos ensued.

It’s not that I didn’t contribute to the household. I had learned to drive by that time and had a car. I tried to pay forward all the times other people had given me rides by offering to my roommates. I helped get furniture. I cleaned when I could. I always smiled. I loved the house and my friends, and I still do. I tried my best not to be a parasite, but there is no denying my nature. I’m Asiatic, ergo, parasitic. COVID-19 is evidence enough.

***

In my Fall semester class I taught a story by Rudyard Kipling called “A Germ Destroyer” (1888). It thematizes the spread of cholera in the British Empire and colonial efforts to combat the disease-causing microbe. It involves a case of mistaken identity: two characters, one named Mellish and the other Mellishe, the former an inventor studying cholera in Bengal and the latter a businessman from Madras, want to meet the Indian Viceroy in Simla. The Viceroy only has the latter on his schedule, but his meddling Private Secretary, John Fennil Wonder – whom the Viceroy has been meaning to get rid of for a long time — mistakes Mellish for Mellishe. The inventor brings in his “Invincible Fumigatory” — a heavy violet-black powder — which blows up in the Viceroy’s face. Wonder, embarrassed to no end, resigns his post. The Viceroy notes that the promise of Mellish’s invention was indeed fulfilled: “Not a germ could live!” Wonder, the unwanted third, the germ, was removed.

***

I found out about a month ago that my roommates had found a replacement to take on the lease and that I should make my own arrangements. I was excluded from discussion on the matter. That’s just as well, because in the coronavirus pandemic, social distancing is the norm. But I could not possibly quarantine myself in a home which has decided on my expulsion — the inhabitants there are quarantining not just from coronavirus but from me. I have signed a lease here in Toledo to live with my sister and mother, together in Asiatic bliss. I shall write my dissertation on parasitism here.

***

“He always knew that he was a third; he always knew that he was only in third position; he always knew that the implacable law is that of the excluded third (the excluded middle). He is well aware of exclusion, wandering, outside the city with its closed gates ; he is not of this world. He is well aware of persecution: here I am alone on earth, excluded by unanimous agreement.” – Michel Serres, The Parasite

***

Photo by Jaël Vallée on Unsplash