UNMECHANICAL: Ritwik Ghatak in 50 Fragments

I don’t think I ended up going to the hospital too many times, but I remember one particular visit quite distinctly. Ma had packed some ilish maachh for him that day. Ritwik opened the container, took one look, and returned it to me, saying, ‘Take this back. And tell Boudi that I am from the banks of the Padma, a single piece of ilish doesn’t cut it for me.’ Ma was quite upset at hearing that. When Baba came back from work and heard the story, he said he would ask Ritwik what this was all about. But I don’t think he got around to it. The two of them, especially Ma, spoke about the incident for long afterwards.

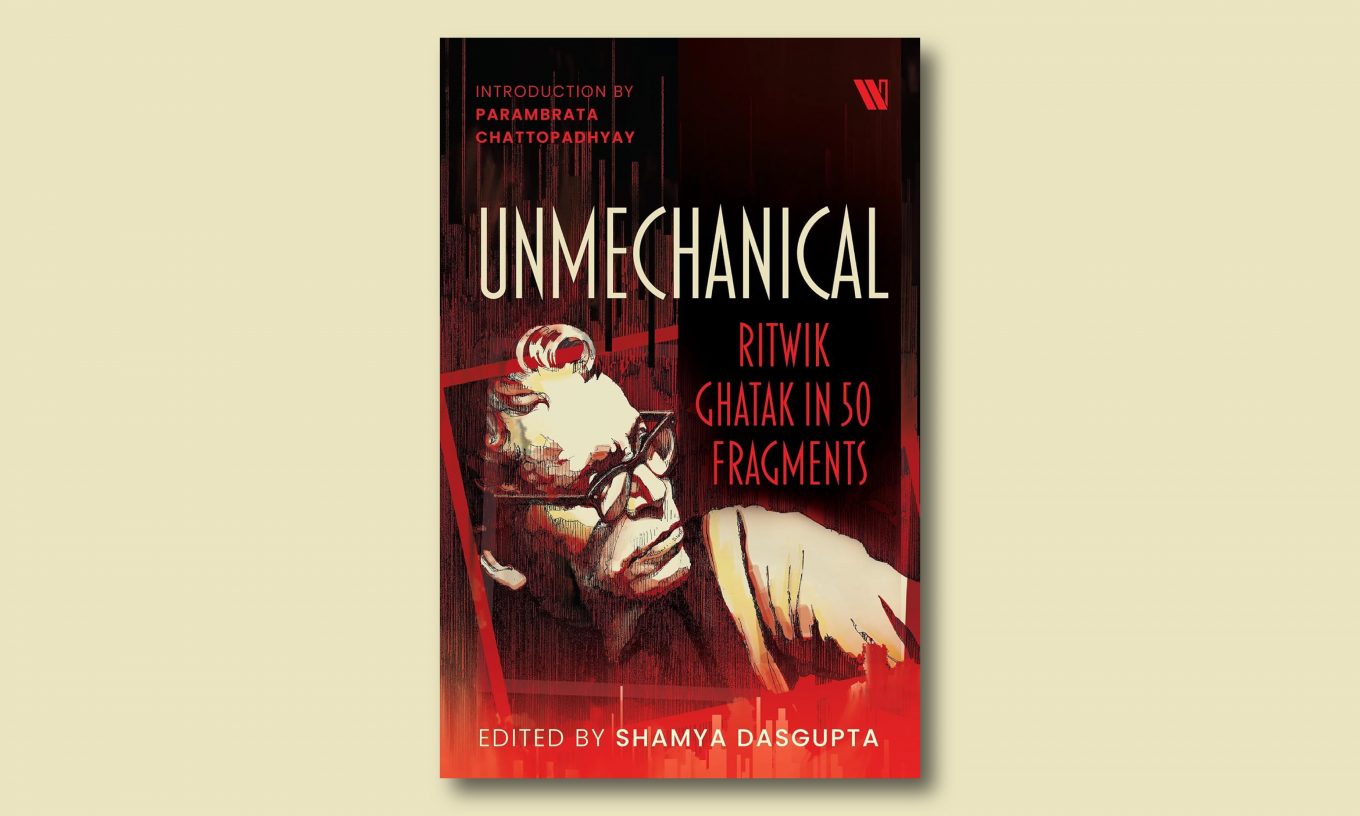

This extract is from the essay, ‘Baba and Ritwik’, by Moinak Biswas, featured in the second section of the book UNMECHANICAL: Ritwik Ghatak in 50 Fragments, edited by Shamya Dasgupta. It is an eclectic take on a life extraordinary – a fitting centenary tribute to a maverick filmmaker, one of the greatest that India has produced, who also wore many other creative hats. Introduced with thoughtfulness and candor by Parambrata Chattopadhyay, the book is structured beautifully under eight sections, and according to the editor, has “something for everyone – the personal and the academic, theories and reminiscences, and whatever falls in between and beyond”. The title is a nod to one of Ghatak’s most unique films, Ajantrik – where a driver is besotted with his old car – which happens to be the most discussed film in the volume. Of the 50 fragments, one is an interview of the filmmaker and four are essays by him, translated from the original Bangla by the editor. These five pieces constitute the section Ritwik, by Ritwik, giving us direct access to his mind. The other sections explore the impact he had on the minds (and lives) of others. Those others include his family/relatives – his twin sister Pratiti Devi, his nieces Mahashweta Devi and Aroma Dutta, and his grand-nephew Nabarun Bhattacharya – who give us A Bio-sketch in Seven Parts (the second section mentioned above), which is predominantly anecdotal in nature. While that is also true of Biswas’ essay (and indeed the majority of the ‘fragments’ of the book at large), ‘Baba and Ritwik’ is emblematic in the way it touches upon concerns that echo all through the book.

The given quote refers to little Moinak taking tiffin (with some trepidation) from his home to Ritwik Ghatak at the Gobra mental hospital in Calcutta not far from where his family lived. Mainak’s father – the singer Hemango Biswas – was a close friend and associate of Ghatak. (He had also been a comrade of Ghatak’s wife, Surama, in Sylhet and Shillong, where they organized cultural programs for the Communist Party). Hemango collaborated with Ritwik in several of his films with his songs; in Komol Gandhar, he sang himself. Not just that; Nagarik was inspired, in part, by a song by Hemango and Jukti, Tokko aar Goppo by conversations with the singer long before the film was made.

Ghatak was admitted into the mental hospital in 1969. By then, he had already directed six feature films, six shorts and two documentaries (and a couple of unfinished fragments), had worked briefly at Filmistan Studios in Bombay, and for a few years at FTII Pune. FTII was perhaps the happiest and most rewarding phase of his life; Filmistan was a writing stint for him that resulted in the story and screenplay for Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s maiden Musafir (1957) and Bimal Roy’s blockbuster, Madhumati (1958); his first film as director, Nagarik (The Citizen), made in 1952, had not yet seen the light of day (and in fact, would not, until after his death); his next two, both in 1958 – Ajantrik (The Unmechanical) and Bari Theke Paliye (The Runaway) – were flops; followed by what came to be known as his ‘Partition trilogy’ – Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud-Capped Star: 1960), Komal Gandhar (E-Flat: 1961) and Subarnarekha (1962, released in 1965) – of which, only the first was a success. For almost two decades before his admission into a mental hospital, therefore, Ghatak had been totally invested in films. But theatre was his first love, especially since his induction into IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association, or Gananatya Sangha, as it was called in Bangla), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India, which, since 1943, led a highly creative movement of politically engaged art and literature, bringing into its fold the foremost artists of the time. IPTA had a profound influence on Ghatak. True to its credentials, he strongly believed in the social commitment of the artist; and thanks to his IPTA years, the love for theatre would stay with him.

In Biswas’ essay, we find that even while being incarcerated in the mental hospital (the inmates did look like prisoners, we are told), theatre did not leave Ghatak. He staged a play, Shei Meye (That Girl) written and directed by him, the cast comprising of both the hospital patients and medical staff. While it drew on his experience at the hospital, it cast the electric-shock administering doctors in a kinder light and had a more positive ending – in that, the protagonist Shanti went back home cured.

Of refrains and overlaps, solidarity and support

Moinak Biswas is not the only one to recall his childhood memories of Ritwik in this book. His niece, Aroma Dutta, is another. Hers is the most heartbreaking piece in the entire anthology, where she recalls the enormous difference in the life and person of her ‘Chhotomama’ (younger maternal uncle) between 1960 and 1971. Reading it is like reading a short story focused on two pivotal moments in the life of a partitioned family: a 10-year-old niece’s first impressions of a still-young and vibrant uncle; and a 21-year-old woman’s coming to terms with the double trauma of recent political violence in her country that killed some of her family members and rendered others (including herself) refugees in India, and the sight and plight of a totally broken and demoralized uncle whom she had adored before. Both years are significant. 1971 was of course the year of the Bangladesh Liberation War. A part of the Ghatak extended family faced forced migration once again, after 1947. The aftermath of Partition that he was so obsessed with as a filmmaker would not leave him in life as well. But 1960 was important, too, personally for Ghatak. It was a lucky year for Aroma to meet her uncle: his life seemed renewed with fresh possibilities at that moment, despite past struggles in the decade before. Meghe Dhaka Tara, the only film of his to gain audience appreciation in his lifetime, was released during the sister and niece’s visit. In fact, Aroma gives a long description of her experience of the premiere show, where she broke down at the end, with her uncle taking that to be the definitive index of the success of the film. She recalls Ritwik, Surama and their two daughters (Tuntuni and Bulbuli) as “A happy, well-to-do, healthy family”; and has the fondest memories of her uncle doing his best to give her a good time: driving her down to the banks of the Ganga, taking her out shopping at New Market, dining with her at his favorite Chinese restaurants in Park Street, all the while calling her affectionately his “Bangaal Ma”. The person she met in 1971 was another person altogether – betrayed by life, drowned in alcohol, and banished from his family (now with the additional member of a son) who lived separately in Sainthia. Her trip to Sainthia, where she is witness to the pathetic deterioration in the relationship between Ritwik and Surama, speaks volumes about what professional/artistic failure and the lack of regular income can do to the fate of a family, with children unfortunately having to face the collateral damage of such a situation. Some future filmmaker could develop a whole new Marriage Story just out of that one scene Aroma describes at Sainthia!

Aroma apart, Parambhattarak Lahiri gives us his experience of playing the lead as a child actor in Bari Theke Paliye(which was produced by his father, Pramod Lahiri). And we also have Maitreesh Ghatak reminiscing his meeting with his ‘Chhotodadu’ (youngest granduncle) in 1974, asking him whether he had made Haathi Mere Saathi – to which he “responded affectionately, with an impish grin, ‘I wish I had, kiddo, then I would not be in such a sorry state.”

Ghatak’s involvement with theatre also features in several essays, notably by Kumar Roy (‘Ritwik’s love for the theatre never went away’). Ghatak was the one, we come to know, who had introduced Roy to Sombhu Mitra in Calcutta in 1948, and was instrumental in the creation of the group ‘Bohurupee’. But their theatre association actually began in 1945 at the University of Rajshahi, where they were both undergraduates (in different streams). The legendary English Professor Subodh Sengupta then headed the institution and took a keen interest in theatrical performances by students. Roy recalls a failed staging of Tagore’s Raja in the university auditorium, which Ghatak, undeterred, managed to later stage elsewhere in a local theatre. Theatre would continue to stoke his creative fire in the decades to come.

Amborish Roychoudhury traces the arc of this passion in ‘A means to an end: Ritwik Ghatak’s life in the theatre’. He starts from much before Ghatak’s University years at Rajshahi – with an eleven-year-old Ritwik “deftly playing Chanakya” in Dwijendralal Lal Ray’s classic, Chandragupta, at Maddox Square Park in Calcutta. Next, watching Bijon Bhattacharya’s Nabanna in late 1944 would be a turning point in teenager Ritwik’s life; later, he would often collaborate with the celebrated playwright, their age difference of almost two decades melting before their shared passion for this art form. Induction into IPTA in 1948, as already mentioned, would be the true beginning of Ritwik’s life as a theatre practitioner, where he acted in several plays under Sombhu Mitra’s direction; he would also go on to serve IPTA in some administrative capacities. 1951-52 saw Ritwik starting to write his own plays and coming up with three in a matter of few years – Dalil (1952), Jwala (1952) and Sanko (1953-54), the first and third foreshadowing his cinematic preoccupation with Partition. This was also the time he began collaborating with Utpal Dutt’s Little Theatre Group, staging Tagore’s Bisarjan and Shakespeare’s Macbeth (among others).

In his ‘Editor’s Note’, Shamya Dasgupta mentions “some overlap among the essays”, which, he says, “didn’t take anything away from the overall yarn for me”. The reader, too, feels the same – as the editor hopes. But more than the overlaps, it is the refrains that strikes the reader. Childhood impressions of Ghatak and his passionate involvement with the theatre – as described above – happen to be two of them.

The most surprising refrain in the book, though, is the solidarity and generous support that Ghatak received throughout his filmmaking career by close friends and associates. Surprising – given his legendary reputation as a flop director during his lifetime who posthumously became fêted as one of the three ‘gurus’ of Bengali cinema (along with Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen, who unlike him, got the recognition they deserved while they lived), and especially given the fact that he was driven to alcoholism by the indifference of the world to his art which in turn led to his premature death at the age of only 50. In reality, there were several who stood by him and supported him during prolonged periods of financial uncertainty or failing health – foremost among them being some of his producers. Three of them – Bhupati Nandy, Pramod Lahiri and Biswajit Chatterjee – are people who not only financed his films but with whom he also lodged free during the making of their films, in Calcutta and Bombay, at different points in his life: as a bachelor, with his family, and separated from them. Another – Habibur Rahman Khan – was most indulgent and a constant companion who looked after his health while shooting his penultimate film in liberated Bangladesh. The fate of films is not in the hands of any producer or collaborator, but their generosity and support do have a bearing on the making of films. So, it was with Ritwik Ghatak. Most of the films he was able to make at all would not have happened if he did not have these people in his life who believed in him and his vision. Who gave him the “small corner” that he had recommended the owner of Filmistan to create for his employees, while resigning – a space for experimental filmmaking. One that spoke to the realities of the times with undiluted honesty and integrity.

Associates and mentees, academics and cinephiles

If the generosity of friends and well-wishers made the making of Ghatak’s films possible, the talent of his creative collaborators and associates made his films the unique experience they are. We find their voices in Ritwik and I, Part One: The Collaborators – the most interesting section of the book. It has interviews with or pieces by some of Ghatak’s closest associates – his producers Pramod Lahiri and Habibur Rahman Khan, his cinematographer Dinen Gupta, and the actors who made his films unforgettable: Supriya Choudhury, Madhabi Mukherjee and Anil Chatterjee.

Ritwik and I, Part Two: The Auteurs gives us the other end of the spectrum from his collaborators – the perspectives of those filmmakers who have been influenced by his work. It is not surprising at all that, apart from Goutam Ghose, most of them have a FTII connection: of either being direct students of his (Kumar Shahani, Adoor Gopalakrishnan) or having met him there later in workshops conducted by him (Arun Khopkar, Jahnu Barua, Ketan Mehta).

Ghatak’s FTII years echo through almost all the sections of the book. It makes one wonder whether he was perhaps most fulfilled as a teacher, and whether continued teaching – of being in the presence of young impressionable minds, grooming them and earning their love and respect in return – could have saved him from alcohol. His spirit definitely lives on at the institute, in a mural near a wisdom tree, and through anecdotes handed down to successive generations of students in the six decades since his time.

UNMECHANICAL would have been incomplete if it had not taken cognizance of the academic literature on Ghatak’s films. Space is made for that in the section, Reading Ritwik, Writing Ritwik – with some essays dealing exclusively with individual films: Nagarik (by Erin O’Donnell), Meghe Dhaka Tara (by Paulomi Chakraborty), Komal Gandhar(by Manishita Dass), and very importantly, his documentaries (by Sanghita Sen). A fascinating one in this section is by C.S. Venkiteswaran – on the reception of Ghatak’s films in Kerala, through film festivals and the film society movement there.

If academics are given space, can cinephiles be far behind? Three of the most engaging essays in the anthology are by Jai Arjun Singh, Sumana Roy and Brinda Bose. Bose’s ‘Abandoned lives, afterlives’ focusses on the other forms (theatre and films apart) that Ritwik chose for his artistic expression – poetry and short fiction – but abandoned later.Roy’s ‘Ritwik’s trees’ opens up a whole new vista for appreciating three of his films – Meghe Dhaka Tara, Komal Gandhar and Titas Ekti Nadir Naam – seen through the perspective of trees: the way they are incorporated in the narrative of the films, and what they say of the bond between humans and nature in each case.

Singh’s ‘A sort of homecoming: Rediscovering Ghatak’ stands out for its humorous take on the difficulty of accessing and understanding Ghatak, especially when one does not know Bangla. Turns out that it essentially boils down to good prints and subtitles of his films – that is the case with Singh, at least. But what makes the essay fascinating and particularly relevant is that, it speaks to the challenges faced by anyone while trying to understand any artist beyond one’s familiar world; and underlines the essentially autodidactic (and sometimes serendipitous) nature of the process.

Translations, images and illustrations

As many as 10 of the 50 pieces in UNMECHANICAL are translations by the editor. That is a feat in itself; but its greater significance lies in the fact that it collates so much rich material scattered in old Bengali magazines and makes them accessible to a much larger audience. They (these 10 and a few others by other translators) also lend the book its heft: take these essays/interviews out and the book will shrink to a much lesser work.

A centenary tribute to a great filmmaker can’t be imagined without images from his films. It is to the credit of the editor and the publisher of UNMECHANICAL that they have given generous space to these images, along with posters and book covers, in addition to numerous photographs of the filmmaker (sourced mostly from the National Film Archive of India, and some from the Ritwik Memorial Trust and Ghatak family archives). They not only contextualize the content of the essays, but add a rich visual element to the book. Contributing significantly to that visual element are also the illustrations by Soumitra Adhikary that preface the eight sections of the book. Each of them depicts a key moment from one of the eight features of Ghatak, arranged chronologically in order of their making – starting with Nagarik (1952) and ending with Jukti, Takko aar Goppo (1974). This is the most delightful feature of the book, adding a dose of graphic narrative to the 465-page tome!

There are also images galore that waft up from scenes in the innumerable anecdotes strewn all over the anthology. The most beautiful of them all appears in the piece by Habibur Rahman Khan on the making of Titas Ekti Nadir Naam: of Ritwik wading into the river Titas knee deep, on first sighting it, and then bending over, splashing his face with the water over and over… not being able to believe that he is in Bangladesh again.

Let’s leave him there.