Now that Jai Arjun Singh has not written a book in years, among all the writers writing on cinema in this country, I find Amborish Roychoudhury most interesting. His books delight me in the way Jai’s book on Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron and Hrishikesh Mukherjee did.

A good biography on a film personality should blend meticulous research with engaging storytelling. It must capture the subject’s professional milestones and personal journey, providing cultural and cinematic context. Insightful anecdotes, interviews, and archival material add authenticity. The writer’s voice should be respectful yet probing, uncovering lesser-known facets without sensationalism or showing off. Like Jerry Pinto’s Helen: The Life and Times of an H-Bomb, one of the finest biographies I have had the pleasure of working on, which was remarkable given that the author never met the subject. Or Deepti Naval’s A Country Called Childhood, which blends her life story with delectable asides that evoke the era and resonate emotionally with readers. Sathya Saran’s Abrar Alvi: Ten Years with Guru Dutt adopted a narrative form whereby the author intercuts her own voice with the first-person account of Abrar Alvi to provide a fascinating example of cinematic parallel cutting in a book. Or for that matter Gautam Chintamani’s Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna, whose title itself was a masterstroke short-hand for the manner in which the author approached the subject. Ultimately, it should offer a layered portrait that humanizes the celebrity while honouring their contribution to cinema.

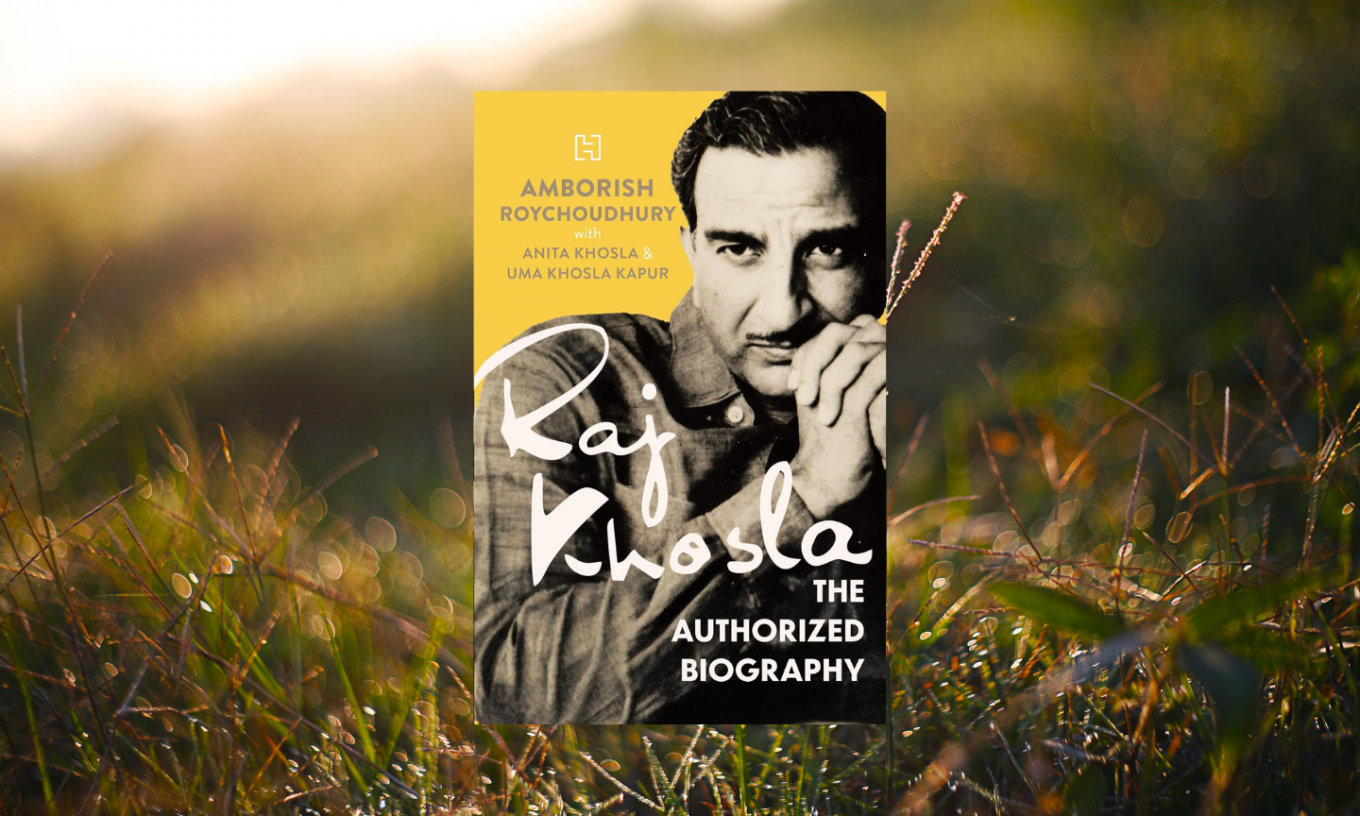

Amborish’s biography meets these criteria. There’s a cadence to his prose that I find in few other writers today. Add to that the fact that he wears his research and scholarship lightly. His previous books – In a Cult of Their Own and Sridevi: The South Years – are rich in research but not showy about that. Raj Khosla: An Authorized Biography is without doubt the best book on cinema published in the last five years. When Amborish first mentioned the book to me, I was as much intrigued about someone actually getting down to chronicling Raj Khosla, as I was relieved that it was Amborish who was doing it.

It’s a long-overdue, richly detailed, and affectionate tribute to one of Hindi cinema’s most underrated ‘auteurs’, though as Amborish mentions in the interview that follows, Raj Khosla would probably abhor the term. Amborish not only resurrects the memory of a director who helped shape the grammar of popular Hindi cinema from the 1950s to the 1980s, but also situates Khosla’s legacy within the broader evolution of mainstream Indian film-making. Combining thorough research with lucid storytelling, the biography serves both as a document of record and a celebration of cinematic artistry.

Raj Khosla is a name that today rarely surfaces in discussions about great Indian directors, overshadowed by Satyajit Ray in the realm of art cinema, and by Raj Kapoor or Yash Chopra in the popular domain. Yet, as Amborish compellingly argues, Khosla was a trailblazer in his own right. He spanned genres with unmatched dexterity, starting with crime thrillers, venturing into noir, musicals, courtroom dramas, and eventually the romantic and emotional melodramas that defined much of the Hindi film landscape of the 1960s and ’70s.

The book opens with a foreword by Mahesh Bhatt, which sets the tone of reverence and personal insight that informs the rest of the narrative. In the Prelude, Amborish vividly sets out to document ‘the wettest day in the history of Mumbai’, Sunday, 9 June 1991. It’s a masterstroke to set up the narrative. From thereon, the author traces Khosla’s early years – from his days as a music student and assistant to Guru Dutt, to his rise as a formidable director in his own right. His training under Dutt – another master of melancholy and visual flair – significantly shaped his approach to cinema, particularly his use of light, shadow, and female subjectivity.

One of the most striking aspects of Raj Khosla’s filmography, as Amborish notes, is its sheer range. His early hits like CID (1956) and Kala Pani (1958) helped establish the crime noir genre in Hindi cinema, marked by sharp editing, moody lighting, and taut narratives. In Woh Kaun Thi? (1964), he moved into the romantic thriller space, using haunting music and gothic atmospherics to great effect. The success of this film and its iconic songs (‘Lag Jaa Gale’ still lives on in public memory) cemented his status as a director with a distinctive style.

Amborish pays special attention to how Khosla depicted women – both as subjects of desire and as complex individuals. From Sadhana in Woh Kaun Thi, Mera Saaya (1966), and Anita (1967) to Nutan in Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki (1978), Khosla’s women were often mysterious, self-assured, and emotionally layered. These weren’t just love interests – they carried the narrative, shaped the story, and left lasting impressions. The author observes that Khosla offered roles to his heroines that were often more substantial than what male characters received.

The book also dedicates space to Khosla’s use of music – not merely as filler, but as a narrative and emotional force. His collaborations with music directors like O.P. Nayyar, Laxmikant-Pyarelal, and Madan Mohan yielded some of the most memorable songs in Hindi cinema. The author sheds light on how these songs were picturized – often in stylized, choreographed sequences that advanced character arcs or deepened mood. For instance, in Mera Saaya, the titular song is not just a ballad of longing but a thematic crux of the film’s twin-identity plot. In his description of the songs, Amborish transcends nostalgia. He breaks down their cinematic function, their placement in the narrative, and the emotional charge they carried. This is where the book’s strength lies: it not only tells you that Raj Khosla was important—it shows you why.

The biography does not shy away from the personal and professional struggles that plagued Khosla’s later years. As the film industry changed in the late 1970s and ’80s, with the rise of the action-oriented ‘angry young man’ cinema and new commercial trends, Khosla found it harder to adapt. Which is interesting because he rode into the 1970s with quintessential testosterone-charged action films like Mera Gaon Mera Desh and Kuchhe Dhaage (which finished among the top hit films of 1973). Films like Do Badan (1966) and Main Tulsi Tere Aangan Ki had affirmed his ability to tap into deep emotional registers, but by the time he made Sunny (1984) and Naqab (1989), the sensibilities of the industry had shifted. The commercial underperformance of his later films, coupled with personal issues and alcoholism, led to a tragic decline. Amborish handles these chapters with empathy. He portrays Khosla as a sensitive artist caught in the crosscurrents of an industry where fortunes change rapidly. The story of his downfall, though sad, is told with dignity and care – honouring the man while acknowledging his flaws.

One of the book’s greatest achievements is its access to a wide array of voices: actors, assistants, technicians, and family members. These interviews and anecdotes provide texture and intimacy. Sharmila Tagore, Waheeda Rehman, Mumtaz, Dharmendra, even Lata Mangeshkar and Manoj Kumar before the passed away, among others, offer recollections that illuminate Khosla’s process and personality. These testimonies are not just nostalgic throwbacks; they are windows into how films were made in an era before digital convenience and corporate financing.

Moreover, the author’s own voice – curious, passionate, occasionally humorous – ties the chapters together. He avoids academic jargon and instead chooses a style that is readable and engaging, aimed at both cinephiles and general readers.

Ultimately, Raj Khosla: An Authorized Biography is more than a chronicle of a director’s life – it is an argument for his place in the cinematic canon. Amborish succeeds in convincing the reader that Khosla was not merely a journeyman director or a forgotten craftsman, but a film-maker who understood the medium with rare sophistication. His attention to visual detail, narrative rhythm, and emotional texture makes him deserving of the same respect accorded to contemporaries like Bimal Roy or Hrishikesh Mukherjee.

That said, the book does occasionally fall into repetition – particularly when praising Khosla’s stylistic traits. A tighter editorial structure in a few places could have enhanced its pacing. Probably, the only quibble I have about the book is its ‘unwillingness’ to be a little more critical of the films in the final phase. It justifiably celebrates the director’s successes, but seems to hold back its punches when discussing some of the blandest films of the 1980s that Raj Khosla directed. But these are minor quibbles in an otherwise valuable and lovingly assembled portrait.

Raj Khosla: An Authorized Biography is both an act of cinematic archaeology and a labour of love. It rescues an important figure from obscurity and offers a nuanced, well-researched, and emotionally resonant account of a life in cinema. For lovers of Hindi films, especially from the golden era, the book is indispensable. For younger readers and film students, it’s an invitation to revisit a director whose films remain stylistically elegant, emotionally powerful, and thematically rich. In giving Raj Khosla his rightful due, Amborish also reminds us why cinema, at its best, is always personal—even when it appears to be merely popular.

***

What drew you to Raj Khosla as a subject for a biography, and why do you think his legacy deserves more attention today?

As a child, I used to watch more films than I do now. Doordarshan dished out films on Tuesday afternoons, Saturday evenings, Sunday afternoons and evenings — and I saw them all. During one of these sessions, I happened upon a film called Mera Saaya on TV. The director’s name ‘Raj Khosla’ was etched on the screen in glorious calligraphy. I asked my father who this person was, and that’s how I got to know about the job of a director. This stayed with me. Years later, I found the name again in books about Guru Dutt and Dev Anand. Khosla finds mention in any discussion around Guru Dutt or Dev Anand, but only cursorily. So, in 2021, when the Khosla family reached out with an offer to write a biography, I jumped at it.

I have mentioned in the book how his work keeps cropping up in contemporary films and even on social media (remember the ‘how much very much paagal’ meme?) with a vengeance. Lag jaa gale remains the definitive love ballad even for younger millennials — it featured in the Salman Khan starrer Sultan. Jhumka gira re found an echo in What jhumka? from Rocky aur Rani Kii Prem Kahani. People in their twenties hum it. Ye hai Bombay meri jaan, Hai apna dil toh awara routinely features in playlists and Instagram Reels. What makes Khosla especially relevant today is how modern his film-making sensibility was — with layered and strong female protagonists, elegant and immersive visual storytelling, and incredible felicity of genres. At a time when we are re-evaluating the cinematic canon and looking to understand the grammar of popular Hindi cinema, Raj Khosla stands out as a director who mastered both artistry and accessibility. The ability to balance these aspects is what makes his work worth rediscovering and revisiting today.

Raj Khosla is known for his distinct style blending music, suspense, and strong female characters—how did you approach unpacking his directorial signature in your research?

Watching his films was a good starting point. I hadn’t seen most of his films earlier, so my slate was clean. As I watched them for the first time, a whole new world unfolded before me. His sense of humour, his ability to play to the strengths of his actors, and his extraordinary sense of music is evident in his work. He didn’t take himself too seriously at all. He wasn’t out to make the best film ever, or take away all the credit saying ‘it’s a director’s medium’ and all that. He said in an interview that when the film is playing, the director is the one person you shouldn’t think of at all. To make a director stand out is easy, he said. But what was important for him was to set his ego aside and narrate his story through actors — project them at their best. This made his actors feel secure in his hands. Which is why their surrender to him was so absolute.

What were some of the more surprising or lesser-known facts about Raj Khosla that you discovered during your research that made you say, yes, this is what makes it all worth it?

Many know that he wished to become a playback singer, and Madan Mohan made him sing in his debut as a composer: Aankhen (1950). But what blew my socks off was when I discovered how he surreptitiously injected some of his own singing in his films. They were hiding in plain sight, until now. We see that in Kala Pani and in Prem Kahani where he sang for Rajesh Khanna. Or the fact that his first work in films was as a stunt double in a Bhagwan Dada film. He debuted as an actor in a film called Raen Basera — there is even a still from the film with Khosla as a dashing youngster sporting a bandana, which is included in the book. The other fascinating aspect that I discovered was the autobiographical element in so many of his films. What he was going through in his personal life, found expression in several of his films. Was he exorcising his demons? Who knows!

Can you describe the process of sourcing material for this book, especially given that many people associated with his era are no longer around?

I spent around half a decade writing this book and the bulk of this time was spent at the National Film Archives of India (NFAI), Pune and the library of National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA), Nariman Point. The Internet gets a bad rap for being unreliable but if you know where to look, it holds priceless treasure. I found old magazines from the 1940s cataloguing Indian radio programmes which listed Raj Khosla as performer — this was from Google Books. YouTube threw an old documentary by a French crew which interviewed him back in the ’80s on the sets of Meraa Dost Meraa Dushman. The opening credits of a film can provide invaluable assistance. Also, there are a lot of people who are still around who spoke to me, for instance, Waheeda Rehman, Asha Parekh, Asha Bhosle, Mumtaz, Dharmendra, Prem Chopra, Kabir Bedi and so many others … Lata Mangeshkar and Manoj Kumar were still around at the time, and they shared priceless stories which are in the book.

An ‘authorized’ biography with the family’s approval could potentially limit a critical look. Were there any instances when you and the family did not see eye to eye on whether to include any aspect of his life and legacy?

Not one bit. Let me repeat that: not one bit. I was pleasantly surprised by this experience. The Khosla family extended every support that a biographer can dream of and didn’t flinch when I explored certain aspects of his life that could make any daughter uncomfortable. In fact, the only occasions where I held back a little, I did so for ethical concerns.

How do you hope contemporary film-makers and film lovers engage with Raj Khosla’s work after reading your biography?

The world is changing at the speed of thought, and cinema with it. The old order is dying out, making way for the new. In this melee, there is despair and confusion in some creators about what ‘works’ and what doesn’t. It might help them to be reminded of the golden age of storytelling. This is how it should be done — this is how it was always done, with grace and with conviction. Raj Khosla was nothing if not a storyteller. Even at a fundamental, human level, I think his journey is as much an inspiring fable as a cautionary tale.

Raj Khosla started out at a time when someone like Vijay Anand did too, and when film-makers like Bimal Roy, Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mehboob, made their greatest films (each a product of the 1950s). How does Raj Khosla stand vis-à-vis these film-makers when you look back 70 years? While each of the other is regarded as an auteur, that term has missed Raj Khosla for some reason…

I think he would have despised the term auteur. If he wanted his work to call attention to itself, it would have been easy to do that. But he wanted the film-maker to remain in the shadows and did everything to ensure that his actors would shine. He wanted the music and the performances to take all the credit instead of hogging the limelight himself. And this is no idle speculation — I speak for him when I say this. Like I mentioned earlier, he didn’t take himself that seriously. He enjoyed making each one of those films and I think we should simply celebrate that.