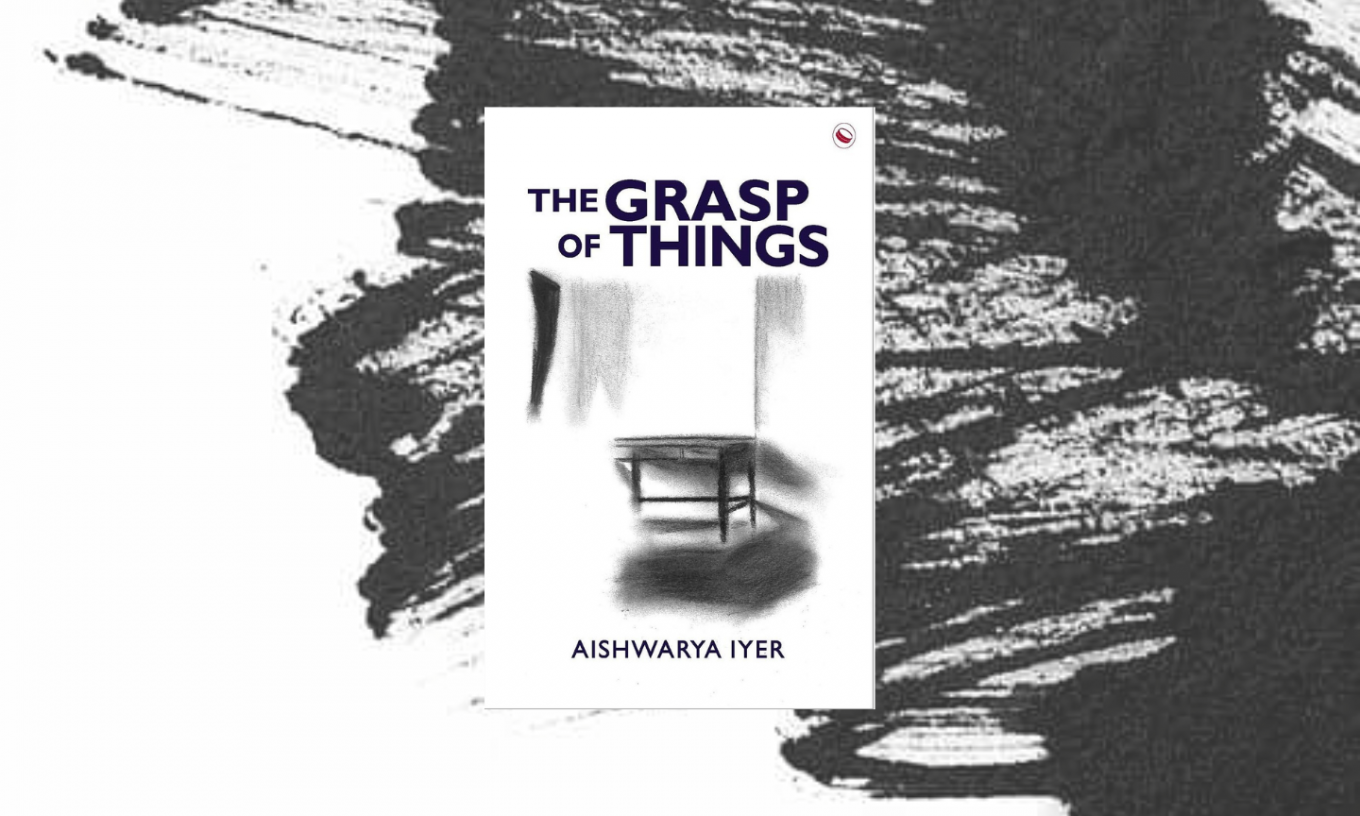

A searching gesture to feel the ‘tension’ between the intangible and the tangible appears to be inescapable in Aishwarya Iyer’s debut collection of poems ‘The Grasp of Things’ (Copper Coin, India 2023). There seems to be a conscious and measured brooding of moral urgency to capture the sands of time slipping through the figures. The blurred image of the cover page, the artwork by the poet herself, creates an insistent patterning of the unseen, the unknown within the seen and the known. As a visual artist herself, the poet’s gesture on the cover page could be an appeal to uncover deeper existential questions of the inner world and seek clarity from the deep epistemological skepticism of the outer world. Due to space constraints, only a few poems could be pressed into critical service. These poems stand out as intimate tattoos of her poetic tension.

The bestiality of the human world is unleashed in the prose poem ‘The Sacrifice’. The rotten remnants of ‘faith’ consume readers with a menacing spirit evoking a world assailed by a wild sense of religious fervor. The poet seems to be posing a moral question of propriety to the human world which is utterly enmeshed in a web of wild violence in the name of religious faith. The world of faith is brought into juxtaposition with the world of religious fanatics where the cruelties to animals go unabated. The poet is satirical of this regime of savagery and the vulgar spectrum of sadistic delight in animal suffering as humanity withers away: “In one absolute sway the steel blades gleamed across the temple walls in tall shadows and the goat’s scream flashed into the sky like a lonely shooting star”

The trauma of festering wounds inflicted by the human world is writ large in the poem. The poem leaves discerning readers paralysed with soul-numbing horror as the specter of savage merry-making unfolds: ”the awful fear of storms, quicksand and death mingled with a roaring happiness, a vile pleasure.”. The ending of the poem with its brooding ferocity is starkly visceral: “Outside the temple walls, under a peepul tree, the mangled intestines of the beasts, purple and green, rose in mounds, flies meandered around blood and the moon turned to flint.”

Can poetry be a redemptive energy to exorcise the dreadful darkness of human arrogance and full-blooded desperation to inflict unspeakable suffering on animals? Such a powerful moral imperative to challenge the age-old wilderness of a shockingly outrageous belief system in animal sacrifice as bloody appeasement to the spirits and the corruption of human sensibilities about non-human animals makes the poem singularly significant in unlocking the extremity of chilling spiritual emptiness at the depths of human psyche.

The beginning of the poem ‘Crow’ with the ominously prescient warning ‘The last crow’ is deeply wrought with empathy and foresight. The poem is an intense and gruesome portrayal of victimisation as the crow bears the brunt of anthropogenic heat and lies ‘bleeding with black crowfuls/ of loneliness.’ The poet records ‘a sacred caw before sunset’ foreshadowing the crow’s torment as it ‘vomits every day by my window/ like a hag by her daughter’. The poet pours out her aggrieved self leaving readers in the shocked stillness of a poignant realisation and its numbness following the heart-rending cry of the bird stifled by the impertinence of the human world of avarice. The poet, who appears to be painfully hopeless but clings to her nebulous hope, cares deeply for the crow as it battles against the ‘deafness’ of the human world. The poem is an artistic triumph in registering a sympathetic urgency against the seemingly inevitable decay of the human world and promoting a dialogic implication within the dynamics of ethics to address the pressing social malaise:

‘I leave my head

and cling to its bones

and feel the black iron call

splintering my jowl

and see it clean the mouth-old detritus.’

A symbolic silence descends in ‘Night Falls’ where the poet takes a dig at the modern man and unveils the paradox of progress: ‘O fool/ in this wet dark/ the moon burns like a stone/ that wasn’t thrashed into cement.’ It is like purging the modern man of his ego as he seems to have exhausted the possibilities to appeal to the sense of beauty. Thankfully, man has not enslaved the majestic ‘moon’ in a paradigm of human progress. In the tussle between beauty and progress, the poet asks: ‘The moon has left us behind, or / We have surged ahead.’ The poem, a nocturnal narrative of engaging characters like the city and the train, trees and birds, ends on a note of long-awaited confession: ‘My body emerges on the sea’s surface.’ Is the body the artistic vision waiting for a fecund space to create poetry and reach its full flowering? Who knows! Readers are left in a spell by the omniscient narrative perspective of the persona. The ‘body’ becomes a figurative implication of a new beginning, a new dawn after the ‘night falls’. This act of emergence could be an act of reconciliation to string together a plethora of impressions through an objective correlative into an organic whole.

The redeeming act of love finds its eloquent expression in ‘The Tide of Two Bodies’, written in response to Octavio Paz’s poem ‘Two Bodies’. The poem is an intimate glimpse into the ritual of lovemaking. It recalls Paz’s poem ‘Before the Beginning’ that ends both with the consummation of mystical raptures and prophesy:

‘we are a river of pulsebeats.

Under your eyelids the seed

of the sun ripens.

The world

is still not real;

time wonders :

all that is certain

is the heat of your skin.

In your breath I hear

the tide of being,

the forgotten syllable of the Beginning’

The above poem is an invocation of all-encompassing ‘night’ that culminates in a love union: the body and the soul. While in Octavio’s ‘Two Bodies’ ‘night strikes sparks’ in ‘two bodies’, in Iyer’s the ‘tide of two bodies, before they become one,/ Is a hole dug into night, where flames go to die.’ In Iyer, while the ‘eye of night stays open’, in Paz, ‘Two bodies face to face /are two stars falling /in an empty sky.’ In both, the language of tantalizing desire transcends physicality and embraces a sublime beatitude of wholeness. What is the truth of this love? It recalls Paz and his luminous observation in ‘ The Double Flame’ which is worth-quoting: ‘The equation of appearance and disappearance, the truth of the body and the non-body, the vision of the presence that dissolves into splendor: pure vitality, a heartbeat of time.’ This creative act of communion intuits eternity!

The poem ‘Reflections’ has Platonic overtones by way of the interplay of light and shadow. The ending of the poem merits attention: ‘What are we, but shadows! Pure forms moved by wind.’ While the former recalls the Cave Allegory with the ‘shadows’ as symbolic of unenlightened moral consciousness, the latter with the use of the phrase ‘pure forms’ conjures up the discernment of Plato’s metaphysics, the Theory of Forms. The poem, which begins with a surreal evocation of shadows and lines, modulates into a romantic confession of oneness till it is disrupted by a philosophical narrative at the end. What animates the poem is a sense of kinetic swiftness of a lot of telling images and objects in search of a ‘newer embrace’ through dreams, pompous self-immersion, delusion, and the reduction of a philosophical truth in a solemn way.

On the whole, the poems in the collection are revealingly philosophical and existential. Readers might feel intimidated by the density of insights implied in the poems in their effort to unpack the ironies inherent in the conjunction of the unreal real and the real unreal. This tension, sculpted with unalloyed passion, precipitates philosophical and ethical questions. Failing to figure out the inevitable reduction of life, the poems at times are ‘vigorously’ complex as the poet wishes to indulge in inner monologues looking at the leftovers of life, the discursive position of social representation, the intertwining of erotic and psychological underpinnings, the pursuit of self-understanding through the grasp of the world, and, finally, the inter-subjectivity nurturing the mutuality between the lover and the loved.

Images, ensconced in intensely rendered settings, chart pathways for readers to grasp things or to see the elephant in the room. In an age where ‘visibility’ is compromised due to blind ideological postures, the poems reconcile the banal and the perennial. The realm of everyday life creates a dreamy vista pushing through the confines of reality as the ebb and flow of time continues in this continuum. The collection, with its tethered directionality, startling newness of imagery, and the integrating power of imagination, is a significant publication. ‘The Grasp of Things’ is a rich texture. Iyer is a distinctive voice among contemporary Indian women poets writing in English, crafting nuanced spaces to dwell on the aberrations of our coercive realities and to create an intricate tapestry of impressionistic internality that throbs with the raw power of poetry and its enchanting power to seek meaning, while also reflecting and mediating the liminality of human consciousness.