The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told; The Greatest Marathi Stories Ever Told

It is difficult to select from such a vast and rich heritage of writing, to accommodate identities, literary ages, genres, voices, to describe the selection as the “greatest stories ever told”. What was the process of selection like? I’m looking basically at your thought process, natural preferences, availability of material, challenges that culminated in the final compilation. Did you focus on choosing from the oeuvre of specific writers or did you focus on stories you loved?

Dr A. J. Thomas: The series title, “The Greatest Stories Ever Told” is a coinage by the publisher’s team, probably echoing the title of the timeless Hollywood Classic. It probably means, “the best stories” at the most.

I did not focus on choosing from the works of specific writers. I was certainly focusing on the stories I loved. That is why you see in the anthology, brilliant stories by the so-called ‘avant garde’ writers, like Thomas Joseph, U P Jairaj, Victor Leenus, TR, and others, alongside those by the ‘well-established’ ones like M T Vasudevan Nair, O V Vijayan, Madhavikkutty, Sara Joseph, Paul Zacharia and others.

Of course, apart from my vast personal hoard of literary magazines over the decades, I have also had recourse to short story anthologies of all these writers in the very specialized stock in the library of Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, where I worked for nearly 20 years. Iconic anthologies like 100 Varsham 100 Kadha, (100 years, 100 stories), edited by K S Ravikumar, and 60 Kathakal (60 Stories) edited by renowned fiction writer N S Madhavan, the short story anthologies of the modernist /high modernist period, Pathinonnu Kathakal,(Eleven Stories), Pathinonnu Kathakal Veendum(Eleven Stories Again), Pathinonnu Kathakal Thanne (Eleven Stories, Still), edited by V P Sivakumar, one of the pioneers of the “post-modern” Malayalam short story, in one case along with D Vinayachandran, the iconic Malayalam poet and fiction writer, the comprehensive anthology of 33 “post-modern” Malayalam short stories titled Prathibhasamgam (1986), (A Joining of Geniuses) edited by CH Haridas have been my main source.

Ashutosh Potdar: When Aleph Book Company asked me to do the anthology, I thought – how am I going to do it as there are hundreds and thousands of stories in Marathi that are published? And beyond the published stories, there are the stories I have heard or read that are intrinsic to Marathi culture. They have been rooted here for ages in the form of what we call in Marathi – gosht, akhyan, kahani, or katha.

For the anthology, I focused on the stories published in modern-day print-era. There are hundreds of printed stories. I sat with the idea for a few days and recollected the stories that have left an indelible mark on my life, the stories I can’t forget easily, and I started collecting them. I remember them as they, more or less, speak to me, and sometimes, touch my heart.

I grew up in a village near Kolhapur in Maharashtra and then moved to different places in Maharashtra and outside, but, some stories and writers haunt me. They keep coming back to me. There are those stories that are part of not only my reality but also those stories that helped me learn about the worlds beyond my own like those in the stories of Bhau Padhye, Hamid Dalvai, or Urmila Pawar.

I thought I should share these stories with those who can’t read Marathi – those who read Marathi will also read these stories in English translation. They may feel different – nice as well as reflective about the language that they have been reading since their childhood. They too would discover new layers of the stories each time they read it.

Stories are of different lengths, long, short and mini. For the anthology, I looked at the stories set in a wide range of milieus that showcase a creative reflection of human behavior and narrate the vivid worlds and realities of changing societies and cultures innovatively. They represent some of the finest short stories spanning almost a hundred years of story-writing tradition in Marathi. The stories are about the pain of the common man, the cruelty and carelessness of humans towards each other and other life forms, the sufferings of a migrant worker, rural poverty, delicacies of human relationships, complexities of nations and borders, and so on. They are melancholic, humorous, sarcastic, representational, elegant and experimental.

Which literary magazines and little magazines were in circulation around the time these stories were written? How were they received and read at the time of first publication? And what are you own specific memories of reading these stories the first time?

Dr A. J. Thomas: The times of writing these stories spans from the 1950s to the first decade of the 21st century. The Malayalam magazines covering this period are Bhashaposhini (fortnightly first, then monthly – launched by the Malayala Manorama group, in 1892, which was defunct from 1942 and was later revived, in June 1977); Mathrubhumi, the weekly which began publication in 1932 and which is the biggest literary and cultural weekly now; Deshabhimani (since 1942); Janayugam (since 1947); Kaumudi Weekly, edited by K Balakrishnan (stopped in1970); Kalakaumudi (from 1975); Malayalanadu (1969-1983); Chandrika (since 1932); Kumkumam (since 1965); Vanitha (since 1975); Pachakkuthira, and a few more. These were the leading magazines, not entirely literary but also dealing with cultural, social, and political topics.

From the 1970s to the 2000s, the presence of little magazines was very important. In the 21st century they were mostly replaced by literary websites and blogs. The notable literary magazines were Samkramanam, Samathaalam, Sameeksha, Jwaala, Niyogam, Paathabhedam, etc.

Most of the stories published in the anthology received cult status right after their first publication, especially, those by Karoor, Kesava Dev, Ponkunnam Varkey, Basheer, Thakazhi and others. The stories of T Padmanabhan, M P Narayana Pillai, Paul Zacharia, M. Mukundan, Madhavikkutty, Sara Joseph, and most others of the anthology, were extremely well-received at the time of publication.

I remember reading for the first time O V Vijayan’s “Kadaltheerathu” (The Hanging) as an emotionally devastating experience, from a weekly. The mesmeric atmosphere of Paul Zacharia’s “Kuzhiyaanakalude Udyanam” (The Garden of the Antlions) captivated me. Sara Joseph’s “Viyarppadayaalangal” (Sweatmarks) left a lump pushing down my throat. T Padmanabhan’s “Makhan Singhinte Maranam” (The Death of Makhan Singh) threw open the hell-gates of the horrors of Partition, for the first time in my rural consciousness developed in a Kerala village. “George Aaaraamante Kodathi” (The Court of King George the Sixth), opened before me the magic of language in which the portrait of a madman came strikingly alive. M. Mukundan’s “Photo” was an appalling revelation. “Chithrashalabhangalude Kappal” (The Ship of Butterflies) by Thomas Joseph, who is a personal friend, left my heart in pangs, yearning for the perfection that he could reach, in my first attempt at translating it. There are several more, but it will go on and on….

Ashutosh Potdar: The storytelling in written form was first attempted through translation activities in the nineteenth century. Translations of suras and miraculous stories of Arabic-Persian style stories, collections like Stricharitra (1854), and novels like Muktamala (1861), Ratnaprabha (1866), Manjughosha (1866) – were fantastic kinds of literature. The first story by Vishnu Ghanshyam was published in a magazine, Dnyanprasarak in a serial form, in November 1854. Early narrative literature seems to have been nourished by wonderful literature for providing entertainment to the readers or giving them some gyan.

The realistic story-telling tradition is considered to have begun with the writings of Haribhau Apte. His stories, committed to representing social reality through writing, published in the weekly magazine, Manoranjan that he founded and edited, can be considered a starting point for publishing of the modern-day Marathi short story. During this period, the first generation of women storytellers like Girijabai Kelkar, Kashibai Kanitkar and Anandibai Shirke started writing. The writer Shantabai wrote the story “Bichari Anandibai” in Karamanuk magazine in 1896. The movement of writing and publishing new stories in the 1940s and 50s was strengthened through the building of discourse around the form of the short story. Literary magazines like Satyakatha and Abhiruchi played a significant role in constructing notions of literariness around the formal experimentation during the navkatha period. Besides publishing short stories of the contemporary young generation writers, these magazines helped build momentum around a new approach to short-story writing through conferences as well as, most effectively, through critical essays, reviews, and special issues of the magazines dedicated to short-story writing. Abhiruchi, for instance, in its inaugural issue in February 1943, complained that the best short story had become a rare thing and announced a story-writing competition in the succeeding year to encourage new writing. In the same month, another magazine called Sahitya appealed to its readers for an open discussion on why there is a dearth of good short stories in Marathi.

The little magazines started dissipating by the 1980s. They didn’t play an active role in my reading practices. I read these stories mostly through school textbooks, magazines, special Diwali editions or short-story collections.

What are the major socio-cultural, ideological and stylistic influences in these stories? How do they trace the development of the form and its reception among Marathi and Malayalam readers?

Dr A. J. Thomas: In Malayalam, the Jeeval Sahithyam (Living Literature), that rose in the early 1930s, which progressed into Purogamana Sahithyam (Progressive Literature), fired by the socialist zeal, liberated the story from the elite realm and the quotidian and the lowly soon became the themes of story-writing. The various shades of realism, beginning with Socialist Realism, played a dominant role from that time till the late 1950s, when romantic and sentimental realisms gave way to early modernist experimentation, dwelling on formalism, existentialism, and a myriad of other philosophical and theoretical influences mostly from the West. Through the 1960s and up to the mid-1970s we have the rise of modernism, high modernism, progressing to what I term, ‘the various phases of post-modernism or after-modernism’ in Malayalam literature, as ‘postmodern’ does not seem to be a fit terminology for this phenomenon in our National Languages. Now we have the millennial writers as well as the later millennials or ‘GenZ’.

Ashutosh Potdar: The writing of the Marathi short story in modern form began in 19th century. However, the story as a form has been rooted here for ages in the form of gosht, akhyan, Kahani, or Katha. Shorter than a novel and distinct from the traditionally heard (or read) stories and myths, modern-day short story came into practice through the journals and periodicals in the nineteenth-century print era. In the early days, the short story was influenced by the newly established colonial education system, translation practices, reformation movements and existing narrative traditions. Short story as a form was limited to urban, educated, upper-caste people. Writers, especially women, in the early 20th century, living in traditional, educated familial structures began exploring women’s personhood and subjectivity through their stories. Initially, it was in the didactic form of informing the readers on moral values. At the heart of the short story was the urge to narrate a historic event, share an anecdote, or tell a story of an individual.

It was the ‘art for art’s sake’ movement and its insistence on the purity of form that enabled the writers to challenge the didactic nature and explore storytelling techniques. At the same time, the writers believing in ‘art for life’s sake’ focused on depicting social issues and conflicts through their writings. Themes such as contemporary political concerns, India’s freedom movement, Gandhianism, communism and the purpose of literature took center-stage in some of the writers’ explorations. Writers, like S. M. Mate, included in The Greatest Marathi Stories Ever Told, aimed at awakening the readers on how privileged members of the society haven’t paid attention to the basic conditions of human existence.

As post-independent Indian society started to become more complex in the mid-20th century, the prevailing format of the story seemed inadequate and irrelevant. The rethinking of the construction of new literary forms became inevitable to address the concerns of urban writers facing a strong sense of alienation, disconnectedness, and disillusionment through emerging urbanization, machine culture, and industrialization. It coincided with the writings of B. S. Mardhekar (1909–56) who influenced contemporary writers with his nuanced writings on the relationship between life, values, and literature. This resulted in the emergence of the navkatha. It redefined the realistic plot of story-telling to address the contemporary values of the time. Literary magazines like Satyakatha and Abhiruchi played a significant role in reconstructing notions of literariness rooted in formal experimentation during this period. Not surprisingly, the majority of the readership in this culture was urban, rich, middle class, educated, and upper caste. The marginalized voices – of farmers, of women, of adivasis, of the lower-middle classes across different social contexts didn’t find expression in the formal experimentation of navkatha. As the socio-political movements led by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi empowered oppressed classes, outcastes, and women, people from the margin were empowered to participate in nation-building processes through their movements. The navsahitya influenced by Dr Ambedkar and Gandhiji questioned the didactic writings, idealistic realism and the sentimental individualism of experimental modernist writers from the navkatha period. It questioned the existing romantic, nostalgic, and hypothetical reality. The writings of prolific writers and revolutionary thinkers such as Anna Bhau Sathe and Baburao Bagul included in the anthology challenged the single, monolithic, and linear view of modernity embedded in the straightforward understanding of the relationship between tradition and modernity.

Another mode that emerged during this period was the story set in the rural context. They reminded the Marathi readers of human conditions intertwined within the class-caste complexities that the middle-class reader was not aware of. Also, the revolutionary writings of Namdeo Dhasal and the vision of the literary journal like Asmitadarsh encouraged Dalit writers to question the existing caste hegemonies and belief systems through short stories.

Short stories of women writers have evolved within the broader context of patriarchy, changing family structures and power dynamics of human relationships. The larger networks of special Diwali issues have taken the short story readerships to the small-town readers. Writers in the late twentieth century developed a strong sense of their identities and connection to their roots. Influenced by globalization and liberalization, the Marathi story has been flourishing through many narrative voices and addressing diverse socio-economic and aesthetic concerns.

In the Marathi anthology, the stories have been translated by different translators. In the Malayalam, the translations are done by a single translator, i.e., by the editor himself.

A J Sir, what made you decide to translate all the stories?

Ashutosh, what made you go for different translators?

And what difference do you think your chosen approach made to the work of selection and editing? How did it influence your choice of stories?

Dr A. J. Thomas: I had translated the works of a great many of these writers on different occasions for different purposes, over the last three and a half decades. Now, getting to present these writers in a single volume appealed to me greatly. I could go in for the stories I loved and present them in my own English. It saved me the trouble of commissioning different translators for the stories and managing them to meet the deadline! Moreover, it left my stamp as the half-author of all these great texts!

Ashutosh Potdar: After I selected the stories, I invited translators like Shanta Gokhale and Jayant Karve as I thought it was an opportunity for me to better understand the translation process from outside too. I was interested in observing the translators’ work in transferring the expressions of one language to the other. As you will see, the stories selected are diverse in themes, forms, dialects and registers, styles and concerns they address. It was a fascinating and revelatory experience to see how the translators have done justice to the worlds presented and worldviews expressed in the original stories.

We find that much of Indian writing in English has turned to urban narratives. Mines, forests, villages, folklore seem to have receded into the background. Do you see a similar trend in writing of short fiction in Malayalam and Marathi? Have setting and character in short fiction shrunk or lost its experiential variety with rapid socio-cultural, political and economic changes? For example, do you find that the non-human world is not as much a part of contemporary storytelling as in the stories in these anthologies?

Dr A. J. Thomas: I do not think so, Sucharita. In Malayalam, the short story remains that of the urban life, life in the countryside, as well as on foreign strands, what with the burgeoning diaspora, much like it was during the last quarter of the 20th century. Of course, the rural picture of the 60s, 70s and 80s has changed, but no drastic change is visible. It is also to be mentioned that Malayalam cinema of the last two decades also helped the rural life, and the country life remain in focus. Only the absence of the youth, now spreading their wings all over the world as overseas students and as expatriate professionals and workers, is markedly felt. The slow and steady urbanization is visible, and the gradual fading of the rural character.

The representation of the nonhuman world is very much there in contemporary stories. I am also now familiar with the themes of the stories of the first quarter of the 21st century that we are already in. I have been reading up for my next volume!

Ashutosh Potdar: I don’t think so. A new generation of Marathi writers living in small towns and villages are writing about their lives, and concerns in their themes, languages and dialects. The contemporaneity has expanded much to consider writing and reading cultures beyond urban centers. Also, the writers who have migrated to urban centers are looking at the world outside their own. Writers like Vivek Kadu, Kiran Gurav, and Atmaram Lomate are responding to the changing complexities, politics, and relationships in the context of caste, class and gender. Some of them look into their surroundings within wider human and non-human lives. Their ways of seeing and narrating have been shaping the contemporary story-writing form in Marathi.

You experienced these stories earlier as a reader/ critic. Now, as editor/ and translator, you experienced them in a different way, perhaps. There is an emotional, intellectual, creative component to the editor and translator’s work, esp. in the putting together of such anthologies. Could you perhaps share how this emotional-intellectual-creative journey has been for you while translating and/ editing this volume? Any particular story/ stories that stand out?

Dr A. J. Thomas: Truthfully, I felt very much a part of the great literary enterprise of Malayalam over the last 75 years, in a significant way. I also became aware of the historical role I have played in putting together these stories in a chronological frame, covering all the important phases and trends in Malayalam short fiction. The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told, which carries 50 stories, which I term as ‘modern classics’, is indeed a unique volume. Coupled with another 50 stories in the companion volume, The New Wave of Malayalam Short Story Writers proposed for next year, there would be 100 stories from Malayalam, in my selection and translation, of the last 100 years since when the Malayalam story made its baby steps and reached its maturity. It is indeed a great feeling, to be an indelible part of history.

M T Vasudevan Nair’s story “Kaazhchcha” (The Vision), stands out as a beacon of women’s autonomy, which I believe will determine our future.

Ashutosh Potdar: I have been reading stories ever since I learned to read Marathi as a child. I grew up reading stories, especially of Vyanaktesh Madgulkar, Shankar Patil, C V Joshi, Anna Bhau Sathe and Bhaskar Chandanshiv. I read some of their stories in the library in a village I grew up in. And, some in the school textbooks. They have been with me through different phases of my life. I feel like they talk to me. Through the process of creating the anthology, I could go back to the stories close to my heart and read them again. I discovered new meanings in them. Through the process, I could reflect, articulate and curate the collection and put it in the wider socio-cultural context. As a poet, playwright, researcher and teacher, I have been a part of different networks. I have always felt the urge to share these stories with my friends and family members. The editing work allowed me to share some of these stories. It’s an emotional as well as intellectual engagement with the stories.

In working with translation of stories that have stood the test of time in the original languages – rich in nuance, use of dialect and register, laced with satire and folklore – what were your challenges?

Dr A. J. Thomas: Of course, the sharp edges of colloquial, idiomatic usages, personalized-stylized language of each individual author, were the main challenges.

Ashutosh Potdar: The first challenge was to put together stories that are ‘greatest’. As I started selecting the stories, I found there are so many ‘great’ stories but to identify something as ‘greatest’ was difficult. I realized many ‘greatest’ wouldn’t make themselves into the collection. Secondly, I was finding it difficult to decide where to end the collection — what should be the last story. I had to think a lot about this. I spent a lot of time thinking about the span of the stories. I had to make the decision not to include stories of a new generation of storytellers from the last thirty-forty years. That would have required another anthology. Thirdly, as a native Marathi reader, I felt the untranslatability of some of the stories that are originally written in regional varieties of Marathi set within a specific context. In that case, I had to look for the translatability of a story that goes beyond the ‘text’ to enable the reader to think deeply about the universe and relationships. For instance, stories of Shankar Patil, Anna Bhau Sathe or Madgulkar are contained in their ability to go beyond to talk about life, society and culture.

How have readers in Maharashtra and Kerala responded to the translations in these volumes?

Dr A. J. Thomas: Except for Basheer’s “The World-renowned Nose”, translating which I had to employ a language that would read meaningfully in the translated text, circumventing his personalized language-style, which attracted the attention of a certain diehard Malayalam enthusiast-reviewer, I did not face any adverse reaction. I think the readers are wise and understanding to the realities of translating colloquial speech, dialect, folk-idiom, satire, pun etc. possible only in Malayalam. If that liberty is not taken, there will be no literary translation.

Having read through so many stories, knowing the history of the genre and the regional literature so well, what according to you is the most significant aspect that these stories may/ may not have in common that would have made you – consciously or subconsciously – bring them together between the covers of these books?

Dr A. J. Thomas: I think the lure of what we call ‘modernity’—breaking free from the feudal, traditional bonds, providing a great sense of liberation—is a single factor that can be highlighted in this regard.

Ashutosh Potdar: It’s the diversity of stories that has amazed me. The stories in the collection are different from each other in content, form and style. It’s obvious. I wanted to showcase the plurality in Marathi culture. Though they are different from each other, I thought there is some Marathiness in it in the way they are contextualized. It’s also the way characters in the story speak, eat, behave and think. The Marathiness informed my process of putting the anthology together.

The stories we read, write, love, have a pan-Indian similarity in terms of experience, yet voice, given the regional context, is different – a different register, flow, vocabulary, an aural-sensual world inhabited by the characters. Translation into English tends to flatten some of the difference, but what tonal quality or variation would you say marks the stories in these collections?

Dr A. J. Thomas: I think the different shades of satire, irony, dark humor, empathy, compassion, the helpless, yet understanding shrug at the human condition, the supreme sentience towards nature and being enveloped by it—all this marks these stories.

Ashutosh Potdar: Yes, there is something ‘lost in translation’ as stories in one language are translated into another language. But I think the translatability of a text goes beyond mere text. It is into the material and immaterial characteristics of a language. Such characteristics of a language don’t just convey information but transfer emotions, thoughts and knowledge that exist in a particular language. Thus, there is something ‘gained in translation’. For instance, a simple resonance in the way they are spoken by a character in the stories of Asha Bage or Jayant Pawar in the collection are almost audible for the reader.

Fiction bears witness to the times. But it also takes time to shape its responses to situations. How is the short fiction form coping with the speed at which the times are changing, at which events unfold, with shortening attention spans? How difficult or easy would you say it is for the short story writer to respond and create in these rapidly changing times?

Dr A. J. Thomas: I think the form of the short story is the best suited for responding to situations that unfold instantly. It takes only a comparatively shorter time to create, and even publish. Therefore, we have so many stories on contemporary life. Covid19 and the lockdowns provided a very recent example. Much quicker than long-form fiction, it is the short story that dealt with this theme, I think, in Malayalam.

Ashutosh Potdar: The Marathi story has been flourishing over the years. The writers are interpreting the world around them in different ways. In the last few years, the Marathi story has gone beyond printed pages in magazines and Diwali special editions to attract a new audience through digital platforms, audiobooks, and adaptions in the forms of film and television serials. Different and new platforms have provided the short story with more visibility and popularity. It has changed the readership of the short story. A new generation of storytellers from diverse socio-cultural and economic backgrounds has been exploring the short story in unique forms and styles. However, at the same time, unfortunately, writers are mindlessly boxed and restricted into groups representing a certain region, dialect, caste, class, religion, and gender. The short story has been misunderstood as a form of narrating only personal experiences, nostalgia, a pedantic approach toward life, meaningless formal experimentation, and a narrow understanding of history and politics. Storytelling for the hefty details of personal experiences. The shortening attention span has resulted in almost disappeared long story format from the magazines. A quick appreciation of micro-length writings on social media, and the demand-supply policy of popular publishing networks have pushed thoughtful and reflective story writing to the corner.

Are there any stories in these books whose opening or closing lines have stayed with you? Whether for the language, the way it opens or ends the story, or for the images they leave you with. How important are beginnings and endings for you in the short story genre? We’d love for you to give us an example or two that would linger with the readers.

Dr A. J. Thomas: S.K. Pottekkad’s story, “On the River Bank,” ends thus, life-affirmingly: “Perplexed, the king cobra turned around like a rubber doll. Then, as if having lost face, it slowly shrank its hood, turned its head, crawled on the ground, flipped its forked tongue, smelled the screw pine bundle on the Barbados nut bush branch, turned its head once again, moved forward, coiled around once on the bare root, then moving along the base of the pulakkalli tree and among the wild aloe vera plants, it slithered southwards.”

Thomas Joseph’s story, “The Ship of Butterflies” opens thus: “A ship which had begun its voyage years ago, traversed different latitudes and longitudes and dropped anchor near the shores of the island of butterflies which had remained isolated for thousands of miles from anywhere, in the middle of the ocean.”

Ashutosh Potdar: As a creative writer myself, I am fascinated by the description in a story written in simple, fluent language that opens the reader to the rich visuality — like in the stories of Shankar Patil, Asha Bage or Jayant Pawar in this collection. Some of these writers describe a character or an event in a few sentences, and some take their own space to convey their feelings and thoughts. As we go on reading them, the descriptions, intercepted by dynamic dialogues, enable us to look beyond the boundaries of subjective experience and remind us of human conditions, worldviews and narrative forms intertwined in a specific context class, caste, gender or culture. Writers like Shankar Patil start their stories with a gripping beginning that the story form would require. As you go on reading, you get absorbed in the story. As a dynamic storyteller, Shankar Patil takes you to the various landscapes existing in the universe and lets you absorb the complexities of a character. Stories of such writers don’t offer straightforward solutions. They provoke your emotions, make you think, and the story-worlds stay with you for a long time.

***

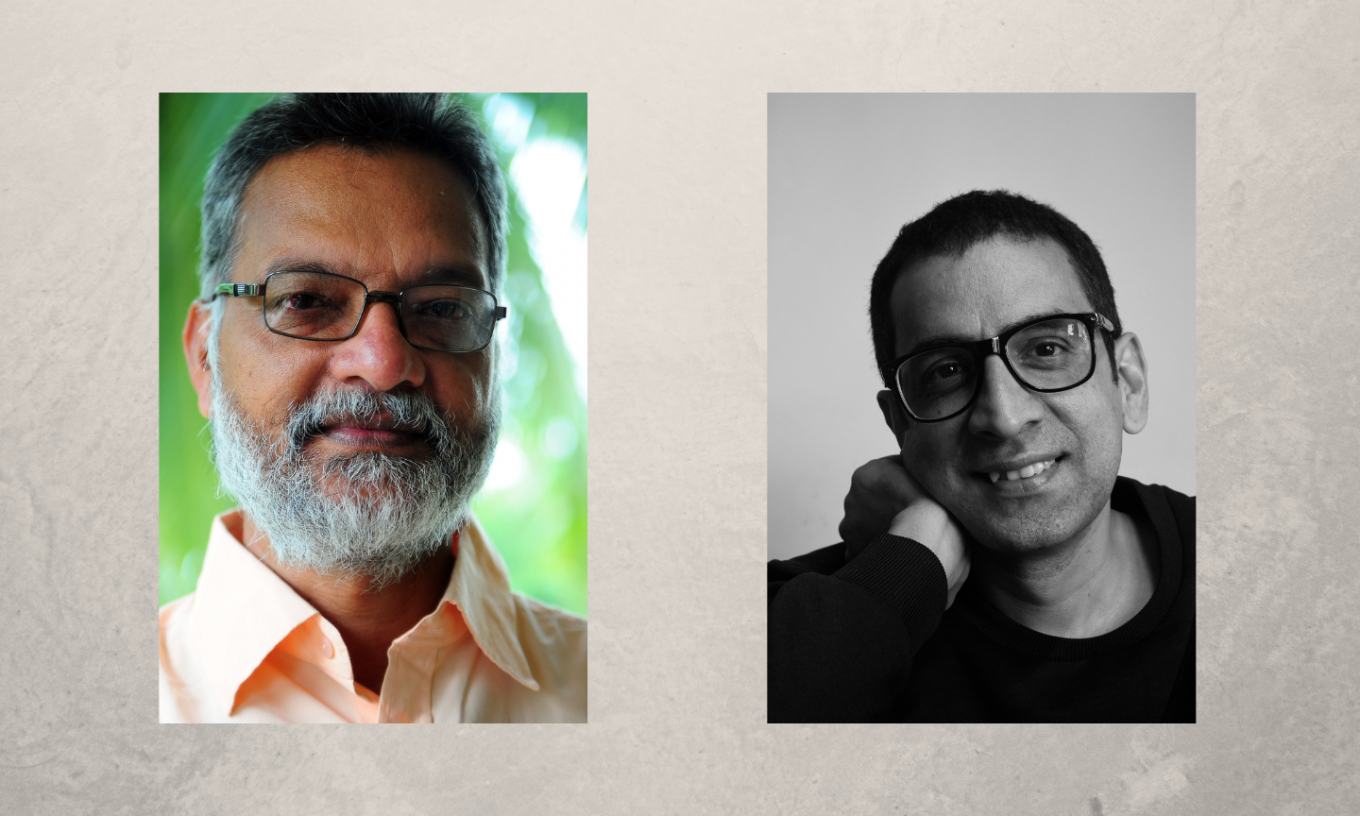

Dr A. J. Thomas is anIndian English poet, and translator with more than 20 books. He has edited, in various capacities, Indian Literature, the bi-monthly English Journal of the Sahitya Akademi (The National Academy of Letters, India), for about seventeen years. He has M. Phil and PhD degrees in English (Translation Studies) and has taught English in Benghazi University, Ajdabiya Branch, Libya (2008 to 2014). He was a Senior Consultant at IGNOU and translator of illustrious writers like O.N.V. Kurup, Paul Zacharia and M. Mukundan as well as the editor of books by U.R. Anantha Murthy. He co-edited Best of Indian Literature (1500 pages in two books and four volumes, Sahitya Akademi). His latest work is The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told (November 2023), an anthology of 50 short stories which are modern classics of the last 100 years selected and translated by him, commissioned by Aleph Book Company, New Delhi. Dr Thomas is a recipient of Katha Award, AKMG Prize and Vodafone Crossword Award (2007). He holds the Senior Fellowship, Department of Culture, Govt. of India and was Honorary Fellow, Department of Culture, Government of South Korea. He has been invited as a Guest Speaker in writers’ conferences and readings in South Korea, Australia, Thailand, Hong Kong, and Nepal, besides centers all over India.

Ashutosh Potdar is an award-winning writer of several one-act and full-length plays, poems, short fiction, and translations. His plays have been performed at several national and international festivals, such as Bharat Rang Mahotsav, the National School of Drama, Prithvi Theatre, the International Theatre Festival of Kerala, among others. Ashutosh has presented his work in a curated show at a gallery in Pune and co-written a performance with an actor and designer in Bangalore that premiered at Sophiensaele in Berlin. Ashutosh has edited the anthology Greatest Marathi Stories Ever Told (Aleph Book Company) and co-edited a collection of essays on performance-making and the archive (Routledge), as well as an anthology of art writing in Marathi (Sharjah Art Foundation). He has also published his research work on literature and drama in English and Marathi in various journals and presented papers at national and international conferences. Ashutosh edits हाकारा । hākārā, a peer-reviewed bilingual journal of creative expression published online in Marathi and English. Ashutosh Potdar is an Associate Professor of literature and drama at the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies (School of Design, Art and Performance), FLAME University, Pune.