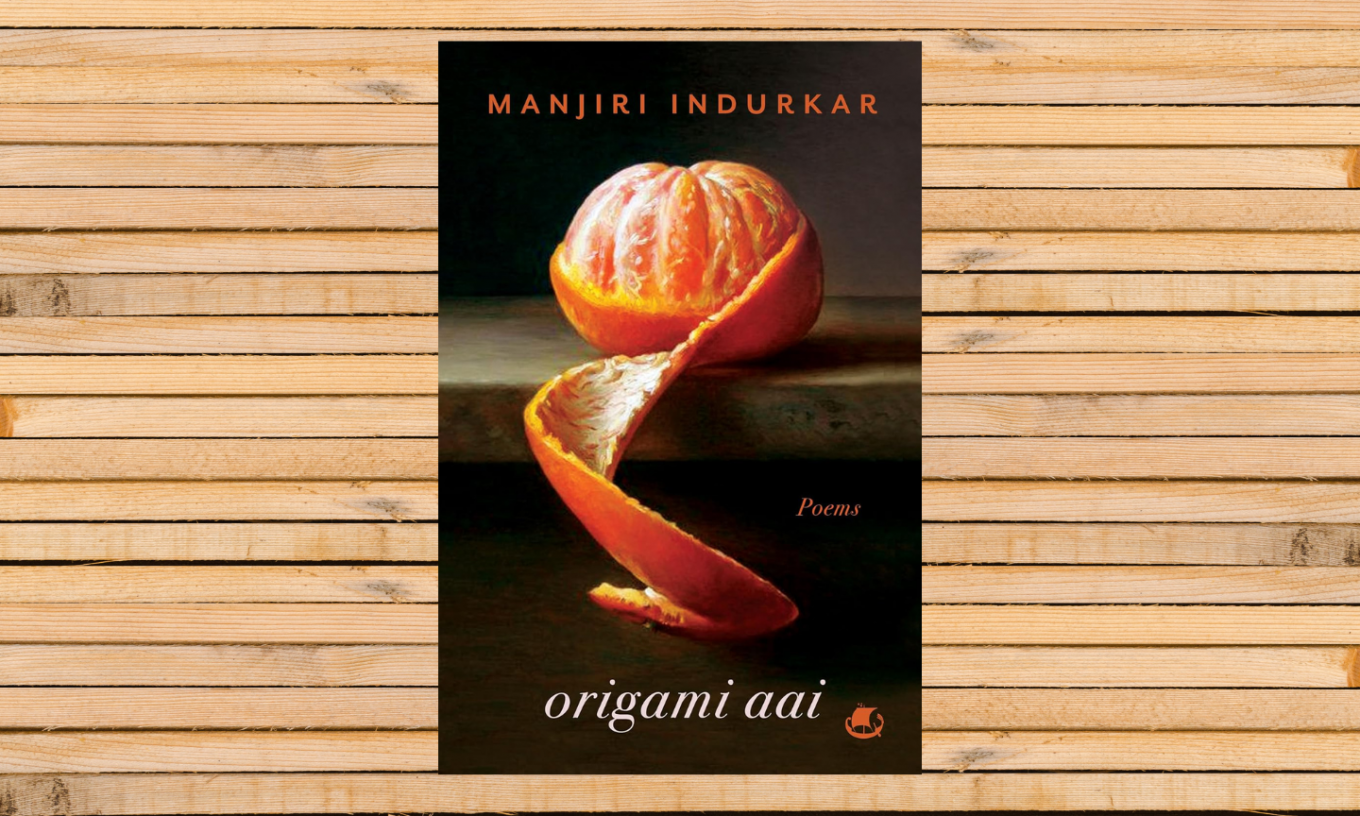

Title: Origami Aai

Author: Manjiri Indurkar

Publisher: Tranquebar

Year of publication: 2023

ON THE LAND OF MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

The foundation of the relationship between parents and their children lies in the act of remembering even the most forgetful moments. Manjiri Indurkar’s Origami Aai prepares us in creating patterns by being delicate towards the scissors functioning. Attachment becomes a scissor, if handled well, it gives shape to forms that we need. At the same time, there are sharp edges here that make people grieve over broken hearts. Intimacy seeks marination, done with care from the subjects and their persona. The book, therefore, is laminated by the thoughts of a conscious mind which works on the scissor to ensure the birth of a body.

In the present world, most of us are not equipped enough to understand the dynamics of different kinds of relationship, including the conditions on which toxic relationships are built on the basis of obsession and violence. In the American television miniseries named ‘Unbelievable’, the creators have tried to objectively dissect the trauma that mostly creeps through conditional judgment of an inherent relationship. This particular aspect does not change in case of controlled compassion between two people who are trying to live each other’s lives. Manjiri’s poems are about sustaining the actions, behavioural approaches, and amorphous emotions of her mother. There is a desire in her to not let these moments go unnoticed.

In the art of origami, an artist works on creating a piece by folding a piece of paper. In case of remembering the acts of her mother, the poet folds her conscious memory to have more than two dimensions for the reader. It is a conscious attempt to make readers walk through the places, moments, people, and minds through the life of Rekha (the poet’s mother). This might be especially impactful on those under the umbrella of the Gen-Z generation, who have mostly missed out on being part of such instances in their own life. While reading Indurkar’s multidimensional poems, one can either choose to be an observer of her world or someone who directly feels its peace and chaos.

Most of us often love adhering to certain cheap thrills in life. Evidently enough, stories, fables and poems – which are written in the genre of pulp for people who do not have the access to the enormity of this life – are based on these very cheap thrills. Manjiri’s poem, ‘My Mother Sings Disco Deewane’, coalesces cheap thrills and the strains of human condition to proliferate a thought that is mostly spoken seriously. This helps us distract ourselves from a state of mind we either don’t like being in, or which we just want to free ourselves from. The phenomenon of moving towards such a freedom is the only living constant.

“She complains of being addicted to laxatives

every night, she drinks 10 ml of EMTY

and jokes about it not emptying her stomach well enough.

She wakes up from her afternoon nap saying,

‘It would be great if I could pass some gas’,

and starts singing. ‘Disco Diwane’, as if

it’s the cure for constipation.”

Osho says, “With progressing age, people slowly start taking a walk towards becoming a child”. It is not just about having grey hair or aching limbs. The child in an aged person thinks with a subsidised curiosity, plays with the senses in an irregular manner, and is conditioned to the definitive silhouette of old age. From absurd comments to unusual complaints, we see the melting rigidity of an age where strength usually takes the upper hand. Through the poem, ‘Diabetes at a Birthday Party, the poet takes us on a journey to the conditional constructs of an age of our life where both nothing and everything can be fun. It teaches us how our attachment keeps us on the right track even amidst them.

The poet writes:

I was always cautious of not using Aai’s comb.

Dandruff was contagious, I always thought.

But it turned out to be hereditary.

Sometimes, out of boredom,

I scratch my head and watch snowflakes

fall on my keyboard.

My scalp bleeds silently as I pick at the white chunks

Spreading on my head like map of Scandinavia.

A different Lata song plays now.

Aai sings but complains about her

Broken note that can’t hold a note.

‘Diabetes, she reminds, will eat your vocal cords.

And I wonder silently.

Who talks about diabetes at someone’s birthday party?

Aai’s life is a cautionary tale.

Many Indian families try to dissociate people from their grief, and in doing this, they often try to manage trauma by using tools such as marriage, outward punishment or intake of alcohol. In the poem, ‘The Gift That Keeps on Giving’, the poet sheds light on the importance of giving time to a person who is grieving, while stressing on the right time to pierce the pain. As an emotion, sadness or grief seems to have been given the colour of either failure, defeat or a step towards a horror story. But that is a limited way of looking at it. Often, it requires the company of a person who is aware of sensitisation, to hold oneself steady when life is going through troughs.

Manjiri writes:

My therapist asks me, were you always this

Sensitive? And I nod in agreement, vigorously,

I once cut the fingers of my hand for revenge

And blamed it on a friend. He cried a lot.

So, I went to him and fed him snacks,

With my bandaged fingers. And told him horror

Stories, sitting on his dead azoba’s chair.

The metamorphosis of the life of human beings, their bodies, and the cycle of our behaviour is strange and at the same time often monotonous. In the Pulitzer Award winning book, The Overstory, Richard Powers blends the body of a human being with trees making it easier for the readers to eliminate the idea of exclusion. The poem, ‘Photosynthesis’, magnifies the vision towards building a divergent vision since the human body quietly manifests the nature of every living organism in the inner self. The assimilation of atrocities and aphorisms is visible in the structure of the human body and its changing forms with every single day.

To enunciate the idea, the poet writes:

I don’t have legs, I just have fins, so

I can’t walk now. I can only crawl.

But I worry that might damage the dahlias.

Soak up the sun; photosynthesis

is a process that shouldn’t be disrupted,

you say. As I soak up the sun,

whatever is left of my skin develops blisters.

To you they resemble water balloons.

Let’s pop them, you say. Water is good

for plants. The dahlias are in full bloom now.

‘Origami Birds’ is a poem and memoir where the poet spills her innocent wishes through scars and small paper boats. We, as writers, try to comprehend our lives no matter how dusted they are. The certainty of the permanence of our lives in the form of a document gives the pleasure of leaving pieces for multiple generations. Affinity for the cradled embrace of poetry is something poets have lost touch with. A poet scissors and joins the pieces through the different stanzas of a poem. The instances which happen in one or many locations are divided by the dimensions of readers and writers. But what should come in the form of a result is a stitched emotion.

Origami Aai is a delicate knife meant to peel the layers of the relationship between a mother and a daughter which is complex by nature. Even though the observation of the poet is seductive, the detachment evident here too, can take readers on a ride where everything may seem tormented. Yet the kindness and gratitude towards the bond comes out with a quiet attitude through every poem.