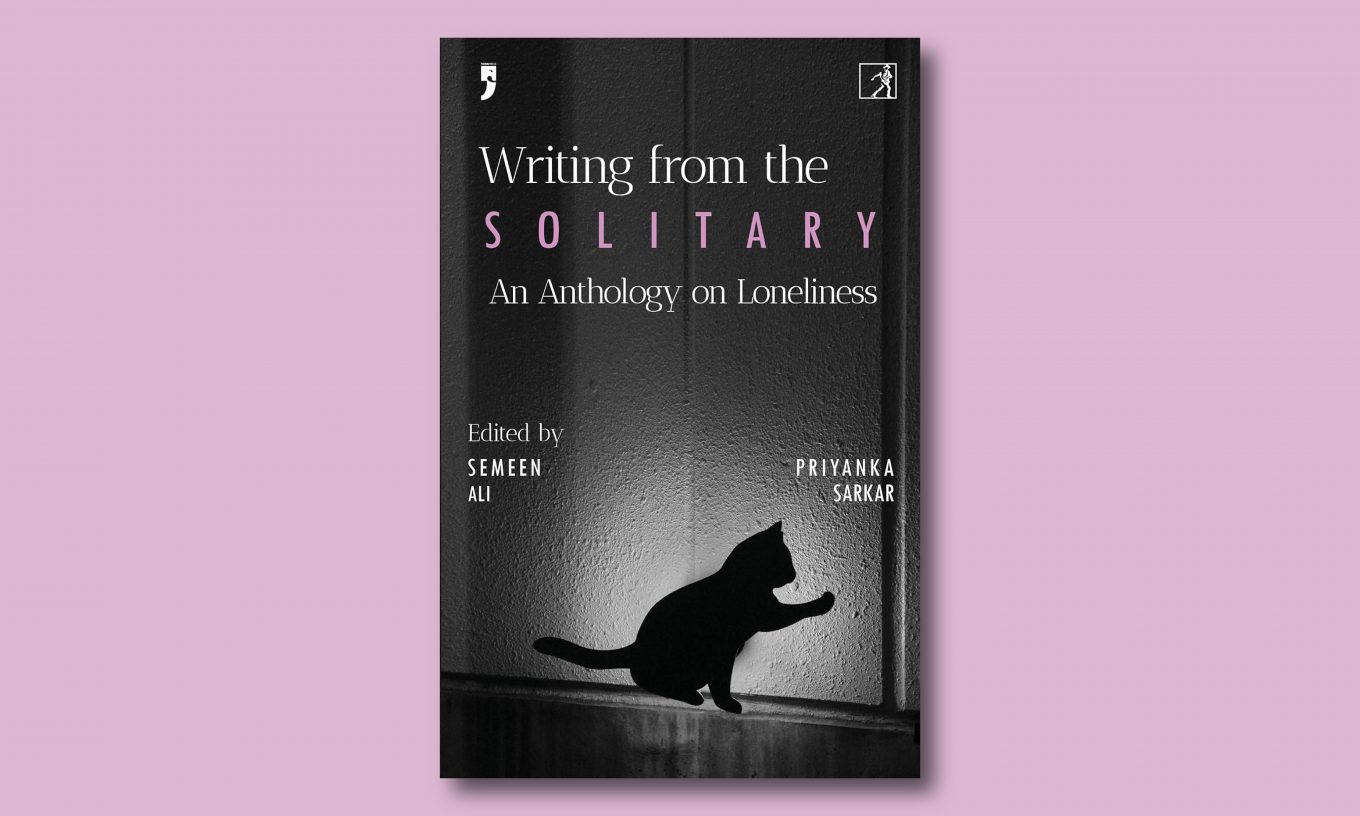

The following is an excerpt from Writing From The Solitary: An Anthology Of Loneliness, edited by Dr. Semeen Ali and Priyanka Sarkar, co-published by Yoda Press1 and Simon & Schuster (December, 2025).

Introduction

Loneliness, as we all know, is not confined by borders or cultures; it is a universal emotion. A recent article in India Today called it ‘a silent epidemic’. Steve Cole, a researcher quoted in the piece, describes it as a ‘fertiliser for other diseases’. The figures are striking: according to the Indian Express, four out of ten Indians (43 per cent of the population) report feeling lonely. The pandemic upset many apple carts and amplified many existing injustices and emotions. Bringing loneliness to the doorstep of most people and making it scream louder in hearts where it already lived was another of its many gifts. It is not surprising that for many young parents, the absence of physical schooling, and hence companionship, at the time sparked fears about the long-term psychological impact on their children, a worry that lingers as we slowly emerge from the pandemic’s shadow.

However, defining loneliness is no simple task. Over time, countless interpretations have emerged, each reflecting different lives, different longings. There has never been, nor can there ever be, a one size-fits-all meaning to the word. And perhaps that is the point: loneliness is not merely a condition; it has become, for many, a way of being. A way of living. It is an experience that each person lives differently, every thinking mind views differently.

In an attempt to approach a definition, one might say that loneliness involves a certain solitude—a quiet, aching isolation that persists even in the company of others. But the truth is that the feeling resists containment. It transcends categories. It cannot be confined to a particular demographic or mapped neatly onto the outlines of a specific community or bracketed within a time period or age limit. It is an experience most of us grapple with at some point, though only a few manage to name it, let alone voice it. As a matter of fact, some keep visiting it at different times in life.

One could argue that loneliness, to be understood, demands time, a luxury not all of us have. But what if it also demands something else: someone willing to listen? In a world that rushes on, full of demands and silences, that one act—of being heard—becomes radical. Too often, societal norms stifle our attempts to articulate what we feel, and so the silence grows thicker, heavier. Think of those closest to you, perhaps those who share your home, your walls battling the same silence, nursing the same ache. It is all too easy to dismiss the emotion, to wave it away as exaggeration or indulgence. But it can be argued that to dismiss is a privilege. And the very act of dismissal affirms that loneliness isn’t always visible, but it is real. Maybe many do not get the opportunity to voice this feeling thinking that they do not have the right space or safety to do so.

There Never Was a Raft

K. Srilata

The day I left, my leaving started to grow,

a river in spate drowning all that had withered

in those parched years,

and all that had blossomed despite.

Soon, things various sunk to the river bed—

that rusty purple Hero Miss India Gold,

that desk drawer filled with the anticipation of pencils,

that spot of sun by the window which had felt like love,

students like birds, their chatter like bird chirp,

an out-of-print edition of Pride and Prejudice,

my belonging like a faded dress.

Even you who say to me:

Come, let’s gather the scatter,

nothing is lost,

there has to be a raft,

even you know there is no gathering,

what scatters only scatters further,

all is lost, it really is,

there never was a raft that brought anyone home.

A City of Epilogues

Manik Sharma

A Passage to Delhi

Scraps of the Indian summer. My first in a new city as I plant my feet, figuratively at least, as a citizen of the national capital. I trawl around the dusty megalopolis, pruning its harsh edges as it prepares to host a global sporting event. Weeks away, the signs are ominously embarrassing as crumbling stadiums hide behind tarred tarpaulins, the grime sliding into the streets as a primer of the bureaucratic bloodletting to come. I’m a small-town boy, someone who has skimmed the gloss of global spectacle by tuning into TVs and radios all his life. This is the big time; of scale, of aspiration, of the yearning to step out of the shadow of funereal histories. Conflict, partition, migration, and the stamp of penury. This wobbly, imprecise leaf, is a bold new chapter. Everyone is a witness, everyone a part of it. Even the ones rolling their eyes at what they see. It’s how nations simply become their people. At which point I can’t help but wonder what prevents Delhi from looking at itself from the sky. Dejected, bemused, but somewhat still hopeful of what it has slowly become.

My reception of India’s—arguably—first city wasn’t a refutation of its charms, or its capacity to host all varieties of chaos. It takes a malleable inner skeleton to be able to house organs at different stages of decay. Which is why, whenever you come to this city, it’s warnings that you encounter first: the people who die in road accidents; the ones who are murdered over casual arguments; chain-snatchers, burglars, gangsters. And smack in the middle of it, there’s me—unhurried, untrained, slow and criminally under-spoken. Armed with a fragile toolkit for engagement. For every migrant in this place or just about any city, the first port of call is to maybe map the potholes, metaphorical and actual. To make sure you don’t fall into them while looking at the majesty and madness of all that’s around you. But mostly to remember your way home.

In the hills, where I had lived until then, existence is vertical. Line of sight uninterrupted. A car honking in the distance feels like a dismissal of the candour we teach ourselves to live with. The hills don’t necessarily imbue softness, they simply offer space to unspool yourself into. Visually, virtually and in just about every manner that doesn’t demand an expression of tangibility. The city on the other hand, expresses itself, makes itself known. It urges you to be mindful of your reach, your place, your stature in the wider scheme of things. Keeping still isn’t an option. The first time you are manhandled by a crowd, the first time you lurch in the city’s buses and trains, it feels less like a journey and more like the last dash home. Move, fight, push back or be run over by people and their conversations. This reluctance to stand still is the city’s primal chord. It’s one rhythm that neither changes nor accommodates someone out of step. The city only writes in epilogues.

Loneliness isn’t what we have, it’s who we are. Some famished by the lack of presence, others crushed by it. My first encounter with Delhi, its meandering bylanes was of the second variety. An only child, I had taught myself the art of observing and mostly bearing stillness. Not as an object, but as this invisible practice of frugality. Wastefulness, as opposed to purposeleness. The rejection of the idea of productivity. Why must life, its units of time have outcomes? Strange as it may sound, the ability to live with yourself can only really be carved out with a lack of material ambition. That sort of thing, however, demands privilege. Financial, emotional, maybe even intellectual. I had the last two. The first one, I realised soon enough, I would have to earn.

To most of India’s small-town residents, all roads lead to the city. Some of us latch onto the hope of discovery, opportunity, while others, to the coattails of escape. The city instantly demands your attention. But before that, it demands your intentions. You can’t loiter, gaze at the whirlwind commotion of the street, or romanticise the culture that punctuates. At least not every day. Small towns and villages have to be raised. A city has to be afforded, dealt with, survived. Run, race or perish, it says.

My first encounter with Delhi’s aspirational underbelly happened in the streets of Rajendra Nagar. Not for the eulogised UPSC classes, but something lesser storied, but maybe just as audacious, a national-level MBA entrance exam. At the time, I wasn’t sure what an MBA was, but in the city, you go where the crowds go.

You do things in small towns because they can be done. Not because you want to do them. In cities, you do them because you don’t want to be the one left out. This feeling, of becoming a collective noun—the state, capital, the nation, the state of the nation—is a first. The town insulates you from you from a national perspective. Here in Delhi, it feels like you’re part of its becoming. It’s both empowering and burdening. What if I don’t want to.

- Updated [December 15, 2025]: An earlier version of this article incorrectly mentioned only Simon & Schuster as the publisher. We have now corrected this mistake and identified Yoda Press and Simon Schuster as co-publishers. ↩︎