Temporary and Permanent

Addresses have slippery loyalties.

Elopers with time, they whisk away

drafts of air, sunshine from a courtyard,

faceless friends. Trick you into letting

go of them but hang around like

apparitions with missing ID cards.

Some become friends. Stalkers

for life. #658 in the government colony,

where I first learned what a newborn baby

and a curfew looked like.

There are those that mimic the

calendar—2011—and become outdated

yearly. Then fade out. Streets,

blocks, gullies form new alliances. Find

fresh candidates to choke with fear. Or

Section 144 of the Indian Penal Code.

My permanent address had an ‘/C’ stuck

to it—a tethered, tiresome appendage.

The troubles that skinny slant caused us,

far from oblique. Postmen spurned the slash

and left my exam results elsewhere. Delivery

boys rang a different doorbell, the seekh

kabab they brought deflating inside a

cold polythene parcel.

In the gully behind this house, my brother

got the name Hari (not because of his godliness but

because his cricketing pals wanted him to

‘hurry up’ between the wickets).

My grandmother gave us her village address

noted with peripheral markers. Spatial jigsaws.

Sprawling fruit orchards, a pond ‘as big as a river’.

The temple my brother found

pieces of when he visited

the village years after

Grandma died

pining for it.

Some address trespass time’s

unpatrolled fence to become permanent

(even when they are temporary). Their

foggy chimera blurs one’s vision.

***

Returning to Taj Mahal

Before landing here, I think about it for months.

In my mind, where all travellers’ dreams gather,

new lists, menus for future entertainment, stew

every day. When I finally step into this walled field

of spices, greens, fish and sweets, this impossible

excess of home, intimate like daily grass once

had been, I’m lost. To be in a Bangladeshi

store is to re-emerge to the noise and sweat of

home after eons of submersion under pasty ice.

This tiny, packed-to-the-gills monument of

masalas, of fish from Padma, of pointed gourd

and Rangpur lime, paralyzes me. Inert, I read

the Bangla print on cardboard fish boxes.

Tapasi, koi, batashi, rui, ilish, kachki.

Deciphering the letters, recommitting them to

memory lets me cross over my foremothers’

rivers. The fish is foreign to my tongue, its

birthplace, the lineage that entraps us both.

At home, my counter displays exhibits from

another Taj Mahal visit. No marble miniatures,

no iconic photographs, not even a picture postcard

that would yellow with age. I open plastic bags to

draw out syrupy sweets, tropical fruits, pickle

swimming in mustard oil. Fish cleaned, frozen

and stamped with Padma certification. Spices failing

miserably to measure up to the singularity of Rangpur lime.

Conjuring up new lists, I vow to keep returning to this monument of love.

Note: Taj Mahal is the name of a Bangladeshi grocery store in Mississauga, Ontario

***

Cumin

Taste is the original rebel. It resists being caged in

closed jars or steaming woks. Like a minstrel’s callused

feet wandering in search for the divine, the ridged beads

of cumin journey the world seeking new tongues.

In her kitchen, the seasoned cook remains patient

for the oil to reach just the right heat.

That moment when the jeera seeds for the daal tadka

crackle is the cadenza her eager ear waits for. Her nose

smells the warmth of sweet sweat releasing from the seed

beads’ oil canals. The scent of earth itself rising. Like jokes,

which never remain what they were when they travel to

new lands, cumin creolizes into fresh flavours and sounds.

Gamun in Sumerian cuneiform, kamûnu in Akkadian, cumino

in Italian, jeera in Sanskrit, the humble seed is a master of

travelling light and charming palates. Crushed coarsely into foul

and hummus, spluttered whole in spicy lentils and the ambrosia

of curried meat, roasted and crushed for the magic bhaja-moshla

touch that transforms a pedestrian ghugni to a gourmet pièce de résistance.

Even without the delicate ellipse of a cardamom pod, cinnamon’s

lanky superiority and a clove nail’s stud-like poise, the cumin wins.

Unlike a monarch and like monarch butterflies,

cumin rejects borders and bigotry and makes new tongues its own.

***

Light and Lightness

On listening to Nawang Khechog for the first time

After eons, an echo. Unflappable, distilled.

Mountains grow limbs when they sense

your need to be healed. The hollow of valleys

enters a long-haired man’s flute and holds

your nerves when they’re too riddled to hold

themselves. In another instant, the rooted

tangles of ochre dread threading your veins

loosen and tear apart. The bamboo swathes

your mind’s map with cascades of frosty mist.

Featherlight. Ablutionary. Pulsating.

Propelled by the flute’s vibrating guidance,

your ears are now eyes. They see light,

beams of softly dancing dust stars. A lonely

memory passes by, one you don’t mind

divorcing after all. Light and lightness, the

flautist’s twin notes, sluice you from hole to whole.

***

Notes:

How the poems — and my thought process — evolved

The poems in Nostalgic for a Place Never Seen came about in a spontaneously serendipitous way. Until a few years ago, I was primarily a prose writer — dabbling mostly in creative non-fiction and the occasional short story. In August 2020, my debut novel, Victory Colony, 1950 was published.

In the spring of 2021, a friend who hosts a poetry-writing collective every April for the National Poetry Writing Month, invited me to join. This was at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic — we were housebound — and true to the cliches associated with poetry and solitude, the moment lent itself well to self reflection. I enjoyed writing poetry in a collective — we read and shared feedback on each other’s works. This not only provided me creative stimulus, it also brought camaraderie and connection at a time when we were dealing with isolation, anxiety and tragedy on an epic scale.

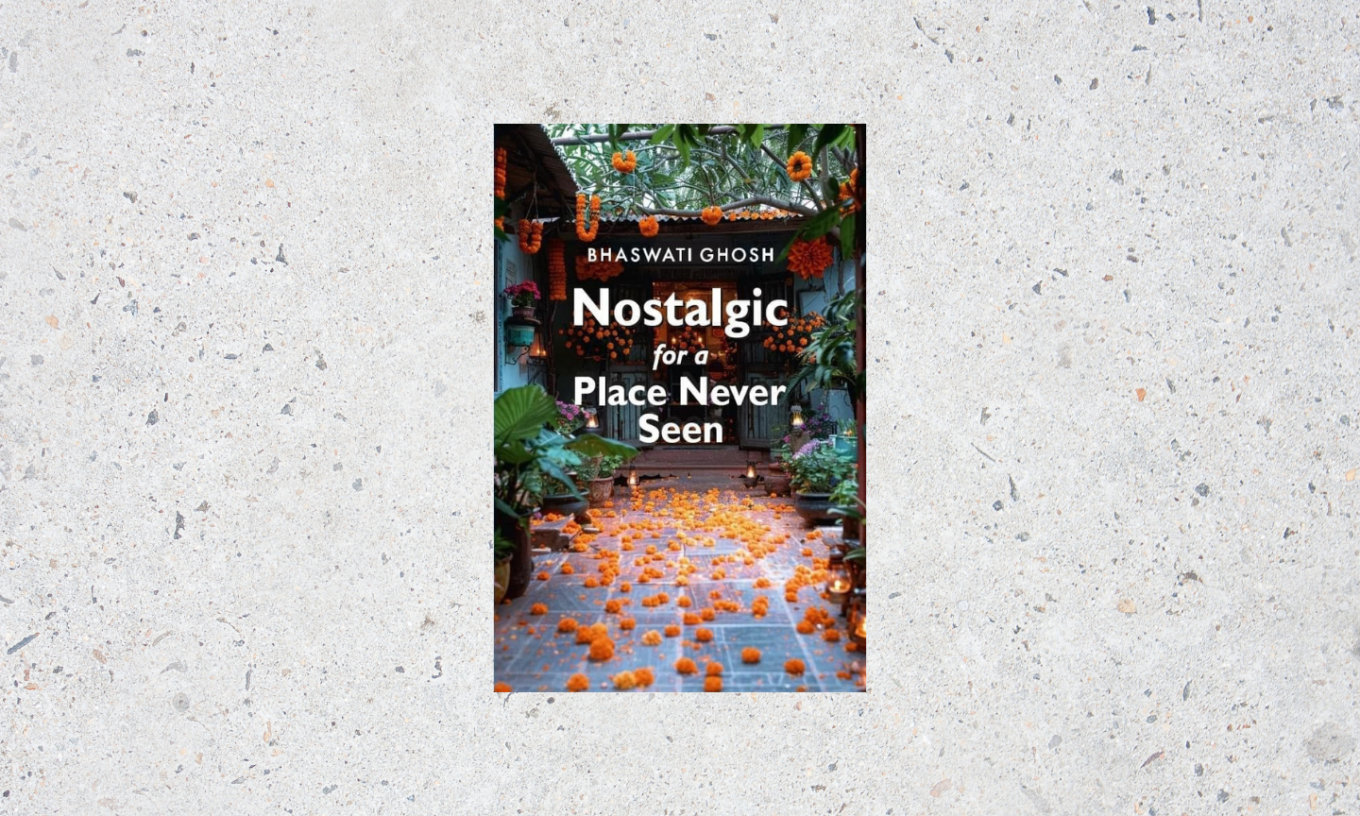

This exercise of writing a poem daily for a month for three years gave me enough poems to think of a collection while also allowing me to hone my craft and learn from fellow poets. Eventually I could see certain patterns and themes in the poems. The book’s title derives from one of the poems in the collection bearing the same title.

Several poems in the book do deal with the idea of location — both temporal and figurative. This made the idea of being nostalgic for a place that’s not merely physical but encompasses more — histories, memories, dreams, longings — pertinent.

A lot of the poems in the collection do relate to physical spaces — dwellings, markets, villages, cities, hills — straddling between continents, atmospheres, cultures and time periods. They raise questions like whether dislocating from one place and relocating to another can really be permanent, except maybe in material terms. The collection contemplates on city life with all its paradoxical oddities and inexplicable pulls. It wrestles with the manner in which the demands of the here and now contend with the salve and cushion of memory. It unlatches the many dimensions of love and takes in with curiosity its lessons for the soul. It observes movement and seeks to inhabit the in-betweenness of journeys.