“For we live with those retrievals from childhood that coalesce and echo throughout our lives, the way shattered pieces of glass in a kaleidoscope reappear in new forms and are songlike in their refrains and rhymes, making up a single monologue. We live permanently in the recurrence of our own stories, whatever story we tell.” (Ondaatje, Divisadero, 136)

The past couple of months have seen me read one Michael Ondaatje novel after another in near random order. The randomness here is an academic insinuation. I was simply allowing a different rationale to my sequence of choices, one that flouts the chronology of the books’ appearance in print with a deliberateness that mirrors the narrative non-linearity of the books themselves.

Nothing about my progression from this Ondaatje book to that was automatic and obvious. At no point did I feel smitten. The charm of Ondaatje’s words and storytelling is not in-your-face winsomeness and congeniality. I could have moved on at any stage: mid-novel, or between books. I even meant to. What makes me curious is that I did not. Imagine yourself returning to a quiet corner cafe on a busy street and feeling an unspoken connection with another frequenter day after day. These five books of fiction were so many tables, and I found myself seated at a new table each time, varying the viewing angle without making any effort to close the gap or rearrange them.

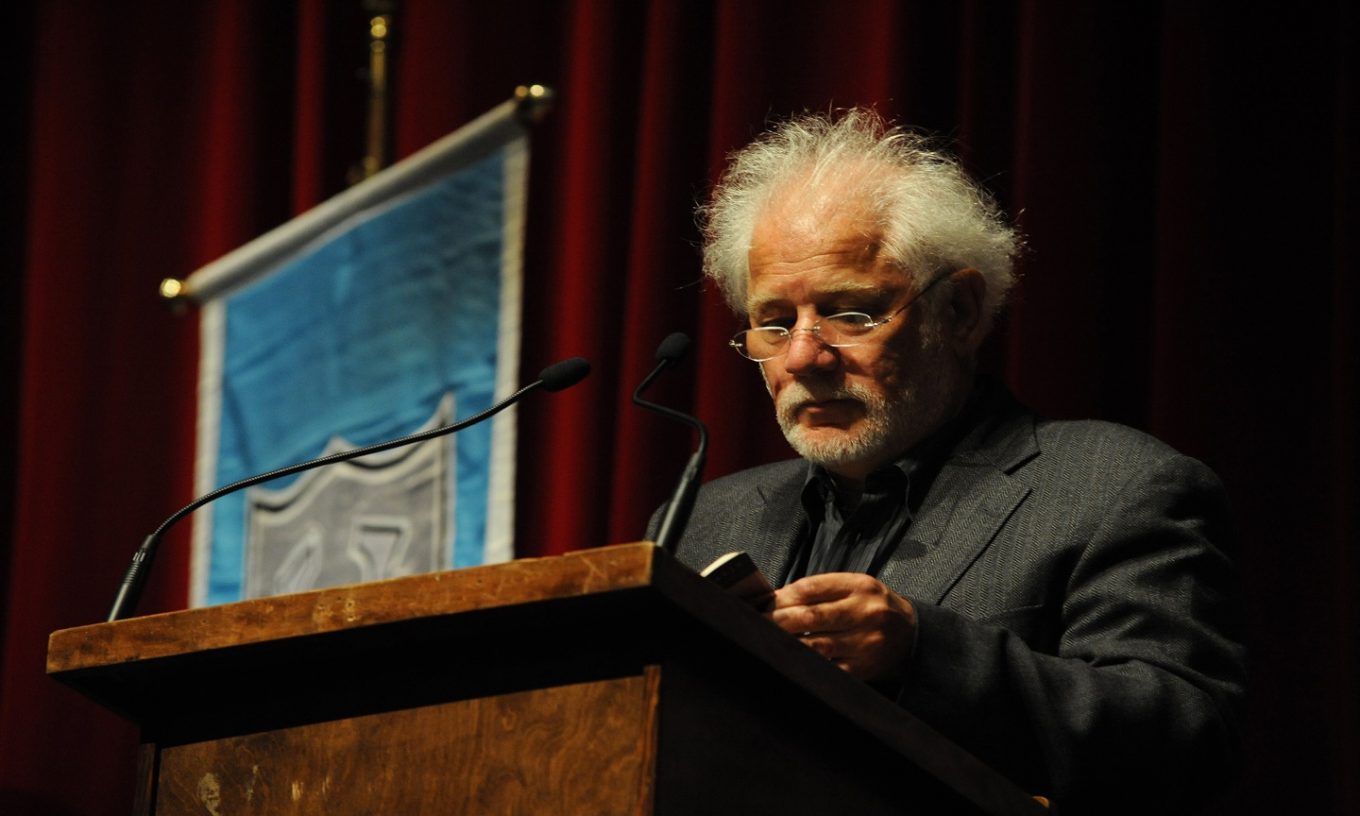

In an interview to Louisiana Channel, conducted in 2014 by Tonny Vorm, Ondaatje wonders aloud as to the point in repeating oneself. He sounds determined to make a habit of breaking the patterns of his own habits. As a writer who professes not to know what lies ahead once a story has germinated. As if to stay true to this conviction, Ondaatje has few qualms about foreclosing the possibility of the reader knowing ahead what his books have in store. Hana’s ruminations refract some of this conviction in The English Patient:

Many books open with an author’s assurance of order. One slipped into their waters with a silent paddle. … So Tacitus began his Annals.

But novels commenced with hesitation, or chaos. Readers were never fully in balance. A door a lock a weir opened and they rushed through, one hand holding a gunnel, the other a hat. (99)

In another interview, marking the success of Anthony Minghella’s film English Patient, Ondaatje tells us how the novel was six years in the making, 1986 to 1992. Here, then, is a writer whose patience with his own randomness is his only acknowledged consistency. The only rule that Ondaatje professes to follow is to stick around and let images lead to stories come together, like those “slow obedient descriptions” of Victor Hugo “that walked towards revolution” in Divisadero (193). One divines a trace of self-reflexive author-speak in the narrator saying about the protagonist in Coming through Slaughter:

But there was a discipline, it was just that we didn’t understand. We thought he was formless, but I think now he was tormented by order, what was outside it. He tore apart the plot – see his music was immediately on top of his own life. Echoing. As if, when he was playing for the right accidental notes. (30)

The narrator in Divisadero is similarly uncompromising when it comes to the pointlessness of biographical divinations:

The skill of writing offers little to a viewer. There is only this five-centimetre relationship between your eyes and the pen. Any skill in the divining or dreaming is invisible … (192)

For the reader of Ondaatje’s novels, then, there can only be the peculiar intimacy of distance, of knowing that there would never be the safety of familiarity.

Yet there is an interesting dividend to reading taciturn books. The more Ondaatje sets out to un-reveal, the more opportunity one gets to uncover the single and singular soul tugging away at the loom of words and stories. Not from esoteric heights, but from some deep, sunken nook.

It was interesting to read Ondaatje’s take on this habit of holding back in order to impel “an active reader” to meet him half-way. This is what he says to Amitava Kumar in an interview published in Guernica Magazine, 23 March 2012:

I wish for an active reader. I think that when I began to write novels, I wanted to keep that element of interaction with the reader that exists in poetry, not just for the reader to be shepherded from A to B to C to D but to participate, and the less you say sometimes, the better it is. You know, it’s the way when someone speaks very quietly, you move forward so you can listen more carefully.

The resistance to repeating himself consciously notwithstanding, his novels organically circle around the shared fundamentals of the human condition – war as a scattering, centrifugal force being the most recurrent of them. “Wounded in a distant battle or by a passion” (Divisadero, 201): it is what epics share. No wonder Herodotus, Tacitus, Milton and Gilgamesh people the minds of his characters alongside Kipling and Balzac and Dumas and Victor Hugo.

I began my reading with the most famous of Ondaatje’s novels, The English Patient (1992). I emerged from this historical romance set against the backdrop of war and espionage towards the end of World War II as if out of the chimera of the desertscape which is its leitmotiv. What lingers on in the reader’s mind is the book’s indomitable romanticism, the heady triumph of love amid the nihilism of war. I went next to Anil’s Ghost (2000), with its intriguing blend of forensic investigation and academic archaeology against the backdrop of the Sri Lankan civil war and its atrocities. Perhaps Sri Lanka’s catastrophic current affairs drew me to it? Be that it as it may, the cold chill to this book, its laconic brutality, unaccommodating of redemptive glimmer, rivals the lyricism of its predecessor.

Reading Warlight (2018) right after felt like a slow submergence into pathos. It too is an end-of-World-War-II novel but one that tells of a boy and a girl abandoned by their mother. The narrative follows the boy slowly and painfully piecing together the truth about their mother’s double life while tumbling up, as Dickens would say, into youth and adulthood. Then, The Cat’s Table (2011) happened: a picaresque coming of age tale, without a care for respectability. Both these novels are markedly Dickensian in their excavation of adult life through the child’s gaze; even as they scrupulously avoid Dickens’s eye for the bathetically comic. Ondaatje is a sombre writer. Patrick, the working-class boy-protagonist in In the Skin of a Lion (1987) moves a fraction of the distance traversed in The Cat’s Table. Yet that short inland passage – from rural Ontario to upcoming Toronto – proves to be no less momentous.

Divisadero (2007), which I read next, begins in America with the start of the Gulf War in 1990 and then crosses the Atlantic along with Anna. As a novel whose narrator seems to be in a more expansive mood to share asides with the reader, Divisadero has helped me read its siblings. The last I read is actually his first novel, Coming through Slaughter (1976). The wrenching portrayal of an early twentieth century New Orleans musical genius slowly losing his mind anticipates the quote from Nietzsche in Divisadero: “We have art, so that we shall not be destroyed by the truth.” (267) Unlike Peter Schaeffer’s Salieri in Amadeus (1979) though, Buddy Bolden is a romantic even at his most demented and the interior monologue style sucks us into the eloquence of madness. It is the traumatic social history of the birth of the jazz sound told through one man’s slide from sound to silence. Ondaatje is far more fascinated by the triangulation of passion, music and the implosion called madness than with jazz music per se. The madness is in a people’s sufferings; and the music is not just a palliative, it is their elixir. It is a new way of reading and feeling music: through the bodies and minds of those who make it. The taut intimacy between discipline and abandon in jazz music, the spillage and slide from the one to the other becomes an implied analogy for the thin line between genius and chaos Bolden is shown as treading.

What do these seven books have in common? Warlight and The English Patient might be said to share a common historical context. In the Skin presents us with the younger lives of Hana and Caravaggio of The English Patient. The latter is set in wartime Italy, just as Divisadero is mostly set in France. The first part of Divisadero, named after a street in San Francisco, is North American in more than just its storyline. In the Skin and Coming through Slaughter likewise. Anil’s Ghost and The Cat’s Table have Sri Lanka in common, the former being a fable of return and the latter, of departure. Yet none of these taxonomic pairings has any fundamental consequentiality, because the author would rather we started afresh with each book. His protagonists travel light and impel the reader to do as much.

Across all these books, the storyline is markedly slow to unfold even as the narrative is forward-moving. The reader is left clutching at straws for clues, while all along sensing the tight grasp of some mysteriously elemental hitherto undiscovered connection propelling them forward. Ondaatje is doggedly self-willed in the way in which he withholds disclosure. His narrators spend a good deal longer thrusting disparate people and stories into the cauldron of a single space or time than in explaining the why-s and the wherefores of those concatenations. Sometimes there are no disclosures at all! Sometimes the disclosures are themselves conundrums that have to be divined. Take for example the dis-covery of Agnes’s identity in Warlight, and the non-discovery of the eponymous patient’s identity in The English Patient.

Happenings and their aftermath have to be recovered by the reader by piecing together fragmented narratives from multiple viewpoints scattered across the entire work. Not only that, sometimes the time-sequence is disrupted while a description of the action is in progress. Take for example the pages where Claire is said to have brought the brutally beaten-up Coop into the house in Divisadero. The description halts there, unceremoniously, and then swerves the reader to the moments before that act of rescue, before her discovery of Coop (35-36). The storyteller lays out an unspoken injunction for his reader. You have to show a readiness for stop-and-go time travel to stay on course.

For me there was a certain déjà vu in the discovery that Ondaatje’s Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (2002) is a fruit of his fascination with film editing. It is as though the narrator of that scene was shuffling the shots around and the reader finds themselves watching a deliberately garbled video reply. In the Guernica interview with Amitava Kumar cited above, Ondaatje makes a pertinent remark:

I think precision in writing goes hand in hand with not trying to say everything. You try and say two-thirds, so that the reader will involve himself or herself and participate in the scene, not just watch.

Even when Ondaatje’s narrator comes round to the factual interweaving, the relief it affords proves to be feeble and by no means fundamental to the magnetism of the narrative itself. By then we have realised that those seemingly unrelated mini-plots do not constitute the real point of interest. It is the power of places and moments to forge intense connections among humans, and, conversely, the power of that connection to give meaning to these places and moments.

Let me illustrate this with my own experience of reading the first few pages of In the Skin of a Lion. The harsh winter chores undertaken by Patrick and his father are utterly alien to my ecological ambit. If it was the veil of sand in The English Patient, it is the haze of cold at dawn here. Even in hindsight, I remain unsure about the function of that opening description, since so little of it actually recurs directly or allusively in the rest of the book. And yet the author gives us to understand, implicitly, that experiencing this physical world up close is pivotal to understanding the formative influences that shape Patrick’s subjectivity. Something similar happens at the Thames docks in Warlight, as also with the seemingly arcane details about cartography and bomb detonation in The English Patient. Ondaatje creates an immersive ambit of knowledge around specific microspheres of living and livelihood.

We all know that is how it should be. Writers of a fiction should be able to write as if they were insiders to the worlds they describe. Ondaatje is modest and grounded when he claims in that Louisiana Channel interview that his research is mostly driven by the need to be able to describe something authentically, as and when the story itself presents him with such an imperative. Truth is, he goes that extra mile to make it happen. This is almost reminiscent of the immigrant Conrad who goes from not knowing a word of English to becoming a native to the incandescent power of English prose. In Ondaatje’s way of seeing, grassroots naturalness must first be acknowledged as foreign in order that it may be nativised and naturalised through effort. There are no short cuts, no easy elisions to this epistemology.

This Conradian connection deserves a slightly longer digression. I had been remembering Conrad as I read In the Skin. Uncannily, there he was; on page 152, in course of a lovers’ conversation between a daily worker and a politically informed actress. Ondaatje’s people are great readers, so that he makes it seem perfectly natural for Alice to have read something as recondite as Conrad’s letters. Exactly the way he makes Katharine in The English Patient read from Paradise Lost (153) and Herodotus’s Histories (246-247). Ironically, the book that begins with an epigraph from Conrad – The Cat’s Table – struck me as the least Conradian of them all. Having said that, I should have been looking for the Conradian strain in the anti-climactic unfulfilment of the journey undertaken by the three adolescent boys and the people aboard the ship Oronsay. Does not Conrad write with gravitas about human beings falling short of their promise? Gravitas and irony are a strange combination. Ondaatje shares it with his fellow emigrant writer-predecessor.

There is something decidedly ekphrastic about the vignettes of lives and livelihoods that Ondaatje creates. Ekphrasis in Greco-Roman epics is not just a form of casual indulgence in spatial detailing. It is a key strategy for assimilating the hinterland of humdrum existence, one that ordinarily lies outside the scope of the grand, central plot – the clash of arms and civilisations. Ondaatje’s narratives combine visual poetry with the technically meticulous prose relating to fields of life and work that might otherwise be deemed too mundane to suit a refined literary taste. The latter corresponds to vivid realism – showing things as they are – while the former makes for equally vivid figurativeness – presenting things with ingenious aptness in terms of other things. The combination makes for a defiantly vitalist gaze on life, and one that reminds me of another great modern, D.H. Lawrence.

As in Lawrence, friendships, loves and enmities stand out for their unflinching intensity in Ondaatje’s fiction. There are, for instance, those evocative words from the narrator as he thinks aloud on behalf of Bolden and his estranged wife, Nora Bass:

…it was friendship that had to be guarded, that they both wanted. The diamond had to love the earth it passed along the way, every speck and angle of the other’s history, for the diamond had been earth too. (90)

There is nothing superficial about this world and the individuals that people it. These are reticent people who nurse their secrets and endure the wounds of their past with a passion that they milk out of lifeforce itself. At one point in Divisadero, we hear Anna’s silent thoughts:

Ahead of them a hare was peering from the border of darkness. She waited for it to take a leap into the light. Curiosity, courage, it was what they both wished for beneath their pounding hearts. (94-95)

People are desperate to stay afloat, and their tonic is usually unconceding, uncategorisable love. Take for example the narrator thinking aloud for Roman and Marie-Neige, again in Divisadero:

They were caught in the attempt at survival among strangers, these two who were strangers to each other. And they saw that anything, everything, could be taken away, there was nothing that could be held on to except each other in this ironlike world that appeared to stretch out for the rest of their lives. (215-216)

In his stories people save other people for nothing more than love. Gangsters bring up little children abandoned by parents. Mothers’ lovers adopt orphaned daughters into their hearts. Widowed fathers bring up other people’s infants born within a week of their own. The corollary of course is that in Ondaatje’s fictional communities, easy moral segregation does not apply. Thieves and authors mingle. Adultery, incest, murderous rage … nothing is taboo. We are in the midst of life in the raw, such as with Sophocles and Euripides. Except that Ondaatje does not write about kings and potentates. His humans are self-made and always ready to start afresh at ‘the cat’s table’, as it were.

Ondaatje would have been a sentimentalist, were it not for his concealment of his tenderness under a thick blanket of unapproachable difficulty. He makes his narratives tortuous and difficult just so that his simplicity and hunger for simple love should not show. It is a violent tenderness. As with the nineteenth-century poet and writer Lucien Segura he writes into Divisadero, being a difficult solitary gives him “space, and a border” (173).

The vision of history that is played out in the lives of these people and families is often profoundly catastrophic. The people Ondaatje creates are often haunted by the trauma of abandonment, people who nevertheless refuse to live placid, run of the mill lives. The English patient tells Hana, conspiratorially,

Kip and I are both international bastards – born in one place and choosing to live elsewhere. Fighting to get back to or get away from our homelands all our lives. … That’s why we get along so well together. (188-189)

Ordinariness for Ondaatje resides in succumbing to, rather than consciously embracing life’s moments of reckoning. Instead, his characters stand out in their little spheres by dint of their incredibly human ability to give, receive, endure and transcend pain and suffering. Buddy Bolden comes across the quintessentially tortured Ondaatje protagonist when he is described by the narrator as wanting a “cruel, pure relationship” (71). Bolden goes on to plead helplessness in the face of the anarchy of attractions he and his peers find themselves engulfed in.

I saw an awful thing among us. And that was passion could twist around and choose someone else just like that. That in one minute I knew Nora loved me and then whatever I did from a certain day on, her eyes were hunting Pickett’s mouth and silence. There was nothing I could do. … We had no order among ourselves. I wouldn’t let myself control the world of my music because I had no power over anything else that went on around me, in or around my body. My wife loved Pickett, I think. I loved Robin Brewitt, I think. We were all exhausted. (80)

That kind of abandon comes from the sense of having themselves been abandoned. They are drifters who live in the moment and then move on and disappear only to resurface in some other place, some other time, like Anna going “in one door and immediately out another”, catching a ride to another name, another life, unbeknownst to her father walking right behind her (138, 140). Liébard the thief in the same novel is described by the narrator as “as much of a traveller in some ways as a blown seed or a bee.” (180)

Consider Mr Nevil’s description of the dismantling of a beautiful ship in The Cat’s Table:

In a breaker’s yard you discover anything can have a new life, be reborn as part of a car or railway carriage, or a shovel blade. You take that older life and you link it to a stranger.’ (98-99)

As testimony to their ability to reinvent themselves, Ondaatje’s persons take on interestingly exotic Henry-Jamesian names redolent with a nostalgia for the mother continent. Take the case of David Caravaggio, who makes his first appearance as an unconventionally humane thief in In the Skin of a Lion and then resurfaces out of nowhere in The English Patient. Liébard the thief and booklover suddenly insists on being called Astolphe, a name he has come to fancy in Ariosto’s sixteenth-century text Orlando Furioso! (Divisadero, 181-182). Anil of Anil’s Ghost goes to extreme lengths as a growing girl to buy her brother’s name (64).

Anil, Katharine, Clara, Alice, Hana, Anna, Ondaatje’s women are very different from one another, and yet all of them are equals of his men in agency, free will, courage and resilience. He writes about them as only a man who has loved woman can do and his writing of the love and lovemaking between man and woman is ravishingly poetic. Yet women are thrust into the eye of storms with as little mercy and must either die, or live to tell.

Clearly Ondaatje believes in the magic that stories can weave. He chooses wars and cities under construction as the site for his stories because such cataclysms allow him to bring together people from disparate backgrounds onto the common platform of survival. Ondaatje is like Anna in Divisadero, “a person who discovers archival subtexts in history and art, where the spiralling among a handful of strangers tangles into a story.” (137) Stories configure new probabilities in the light of which the past is read in ways that reconnect it with the present. Thus we have in The English Patient a Sikh Indian soldier in the British Allied Army stationed in Italy running into a young Canadian nurse tending a Hungarian explorer with a past as indistinct as his unrecognisably burnt face:

Years from now on a Toronto street Caravaggio will get out of a taxi and hold the door open for an East Indian who is about to get into it, and he will think of Kip then. (220)

Notably, Kip, apart from being short for Kirpal Singh also happens to have been Ondaatje’s own nickname during his boarding school days in England. Ondaatje mentions having had this name in course of an interview with Robert McCrum for the Observer dated 28 August 2011. This little correlation tells us how adroit the author is in recreating milieus and details from his own life for his fictional cast. Ondaatje writes his passage into youth as an expatriate in England into Kip’s life, while vociferously denying, in the same interview and in his Author’s Note (367) to The Cat’s Table, any genuine resemblance with his eleven-year-old avatar and namesake there. As a fashioner of fictional truth, Ondaatje seems to see the convincingness of that fiction as his only responsibility. As to the rest, he reserves his right to be disingenuous.

One of the key refrains marking the centenary of the end of the First World War in 2018 was the British Indian soldiers’ contribution in both the World Wars. Here we have Ondaatje, as early as 1992, presenting a Sikh army officer confronting the English patient with the injustices of the colonial situation while continuing to share a deep bond of comradeship in crisis with Hardy, his English colleague:

I grew up with traditions from my country, but later, more often, from your country. Your fragile white island that with customs and manners and books and prefects and reason somehow converted the rest of the world. …

You and then the Americans converted us. With your missionary rules … You had wars like cricket. How did you fool us into this? (301)

This is where Ondaatje’s life experiences as an emigrant is insidiously immanent. This is the other Conradian streak in his fiction: the perception of history as a Noah’s ark, where old worlds and new worlds come together in boundary-bending cataclysms. In the words of the English patient,

Gradually we became nationless. I came to hate nations. We are deformed by nation-states. Madox died because of nations. (147)

History does not tell itself directly. Stories for Ondaatje, as for Conrad, preserve, visibilise and vivify this fact of history. Stories go into the crevices that “the grand story” can never reach. To quote an unexpected authorial interjection in In the Skin of a Lion,

All these fragments of memory … so we can retreat from the grand story and stumble accidentally upon a luxury, one of those underground pools where we can sit still. Those moments, those few pages in a book we go back and forth over. (154)

Ondaatje’s women and men – spies, thieves, convicts, murderers, gamblers, addicts, soldiers, farmers, subsistence labourers, army nurses – are intensely alive at any given moment in time. They work and live in their bodies. The narrator of Coming through Slaughter is probably echoing the author when he describes the policeman Webb’s gaze:

Webb discovered the minds of certain people through their bodies. Or through the perceptions that distinguished them. (44)

Shortly afterwards in that novel we encounter a celebration of the body, grime and all, unimpeded by this abstraction called mind. While writing the body might seem not altogether unusual, my point is that you cannot simply assume its naturalness. Language, even fictional language, is so much of a mentally conceived medium that we do not always expect it to stand in for the thing in itself quite this transparently. Paradoxically, the body narrative requires a prodigious degree of mindfulness. That is what we see in this excerpt from Coming through Slaughter:

In the heat heart of the Brewitts’ bathtub his body exploded. The armour of dirt fell apart and the nerves and muscles loosened. He sank his head under the water for almost a minute bursting up showering water all over the room. Under the surface were the magnified sounds of his body against the enamel, drip, noise of the pipe. He came up and lay there not washing just letting the dirt and the sweat melt into the heat. Stood up and felt everything drain off him. … (46)

The novels then are hardly what we might call cerebral. The words Ondaatje adds to the lexicon of description are not esoteric, but earthy. It is as though the author went to work with the English language in fields, caves, on bridges and river dockyards. What he finds there are words for implements and chores that had all along been there, though unnamed, unacknowledged. Ondaatje marries the poetry of high prose to this earthiness of working-class fiction. In The Cat’s Table, the narrator reflects:

That was a small lesson I learned on the journey. What is interesting and important happens mostly in secret, in places where there is no power. Nothing much of lasting value ever happens at the head table, held together by a familiar rhetoric. Those who already have power continue to glide along the familiar rut they have made for themselves. (103)

It hardly comes as a surprise that novel after novel should sensitise us to the sacrifices made by people working by the sweat of their brow in making cities and civilisations happen. For instance, Patrick confronts Harris in In the Skin of a Lion (248):

-… Think about those who built the intake tunnels. Do you know how many of us died in there?

-There was no record kept.

In The Cat’s Table Mr Fonseka lectures the boys “about the thousands of workers who died from cholera” during the construction of the Suez Canal (173).

The manner in which Ondaatje creates unusual, unexpected intersections of history and geography, Herodotus and the desert, aeroplane-riding and geographical exploration, espionage and war, suggest that history for him can only really be inscribed in bodies and spaces. The vitalism of his writing is a means of writing from within the past in order to make it contemporary with the reader in the present. The past is only ever de-notified as dead at the precise moment of its recognition as past. Staying true to history is for Ondaatje not the same as fettering storytelling to the recapitulation of historical facts. The tectonics of history interest him in the way in which these cause tremors and fault lines in private lives. The tremors in turn lead us back to the global seismic forces of civilisations rising and falling. History for Ondaatje works through people. In this respect, he is like the archivist and historian Anna he himself creates in Divisadero:

Those who have an orphan’s sense of history love history. And my voice has become that of an orphan. … Because if you do not plunder the past, the absence feeds on you. (141-142)

We may perhaps find an allegory of this vision of history in Anil’s attachment to the skeleton she and Sarath have exhumed and reconstructed in order to ascertain its age and time of killing. They carry it about as though it were still a living human, not an inanimate forensic object. History is never dead. And as it happens at the end of the book, history kills. The narrator’s meta-fictional interjection at one point in In the Skin of a Lion would be apposite here:

Official histories, news stories surround us daily, but the events of art reach us too late, travel languorously like messages in a bottle.

Only the best art can order the chaotic tumble of events. Only the best can realign chaos to suggest both the chaos and order it will become. (152)

None of Ondaatje’s novels are long. They are comfortable paperbacks, and yet they recall the paratactic, Old Testament mode of narration that Erich Auerbach conceptualises in ‘Odysseus’ Scar’, the first essay of Mimesis, written during World War II:

The two styles, in their opposition, represent basic types: on the one hand fully externalized description, uniform illumination, uninterrupted connection, free expression, all events in the foreground, dis- playing unmistakable meanings, few elements of historical development and of psychological perspective; on the other hand, certain parts brought into high relief, others left obscure, abruptness, suggestive in- fluence of the unexpressed, “background” quality, multiplicity of meanings and the need for interpretation, universal-historical claims, development of the concept of the historically becoming, and pre-occupation with the problematic. (23)

For Ondaatje, both knowing and letting know are incremental without being linear. Both are progressive without being conclusive. Exits in his novels are unmelodramatic and resolutions non-existent. In place of full closures and disclosures, there is only motion: a sense of the author letting his protagonists go away to make new stories elsewhere while he turns his eyes away and begins a long wait for their reappearance.

A Note on my Method in this Essay

The narrator in Divisadero writes knowingly and derisively of the critical overzealousness received by a youthful poem of Lucien Segura’s, one that was “memorized, explicated, exfoliated in schools until there was nothing left but a throat bone and a claw.” (171) In deference to this cryptic dissuasion, I have written this essay as the “active reader” defined by Ondaatje in the Guernica interview, rather than with academic aloofness. I have allowed Ondaatje’s characters and scenes and the very obliqueness of his telling to lead me back towards his ways of seeing and thinking. My next stop will be his poetry, which, I suppose, has already received critical attention in Douglas Barbour’s book (1993).

***

Works Cited

Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Translated by William R. Trask. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.183999/page/n9/mode/2up , accessed on 20 August 2022.

Ondaatje, Michael.

- Anil’s Ghost. London: Bloomsbury, 2000; Vintage 2011.

- Coming through Slaughter. London: Boyars, 1979; electronic edition: Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Divisadero. London: Bloomsbury, 2007; Kindle Edition.

- In the Skin of a Lion. London: Martin Seeker & Warburg, 1987; Picador 2017.

- The Cat’s Table. London: Jonathan Cape, 2011; Vintage 2012.

- The English Patient. London: Bloomsbury, 1992; paperback 2018.

- Warlight. London: Jonathan Cape, 2018.

Ondaatje, Michael. We Can’t Rely on One Voice. Interview for the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Louisiana Channel.

https://channel.louisiana.dk/video/michael-ondaatje-we-cant-rely-one-voice , accessed on 28 July 2022.

The English Patient: Author Michael Ondaatje and Director Anthony Minghella Interview. July 16, 2016. Manufacturing Intellect. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ScjsILH9Ud4 , accessed on 9 August 2022.

Robert McCrum, ‘Michael Ondaatje: The Divided Man’. The Observer. 28 August 2011.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/aug/28/michael-ondaatje-the-divided-man, accessed on 24 August 2022.

Amitava Kumar. ‘Michael Ondaatje: Ondaatje’s Table’. Interview. Guernica Magazine. March 23, 2012. https://www.guernicamag.com/kumar_03_15_2012/ , accessed on 24 August 2022.