Unpacking my little library

I have always been fascinated with worlds out of sync, out of joint, untimely, filled with non-sequiturs and miscellany. I have always dreamed of secret libraries comprising books that don’t even exist, and I have by and large been out of sync with most contemporary literary production. I think sometimes—not all the time—it helps to be a little removed and out of joint—not out of sorts. I like books that are like puzzles, and those that hold secret languages. I like to find poetry in user manuals, books that talk about beauty secrets, or a children’s primer. In my experience, what I’m looking for, is usually never in the places you’d expect them to be.

What follows is a short list of books that I return to quite frequently, unpacking my little library.

Ich und Du (Martin Buber)

This work has been translated into English as I and Thou, and of Buber’s oeuvre it is the most interesting. It is almost as if all his essential ideas received the most concentrated treatment in this little book of theological-philosophic poetry. He splits the world of relations into two essential word pairs, the world of I-THOU and the world of I-IT. It is almost as if he is splitting the world of relations into grammatical categories. The world of I-IT looks at you as something among other things, for, as Buber argues, wherever there is something in this vast net of a universe, there has to necessarily be something else; in the world of I-IT, thou art a mere thing among other things. But in the world of I-Thou, I stand in relation to you, alone, and that is where, Buber argues, lies the cradle of actual life. This is the centenary of Ich und Du; it first appeared in print in 1923. I carry it around in a little yellow pocket book edition to remind myself to never use or exploit anyone for personal gain.

***

A Shocking Life, Elsa Schiaparelli

This is an autobiography of one of the most fascinating designers of clothes, and it reads much like a bildungsroman. Schiaparelli is able to view herself at times like an ugly duckling and at other times as swan. Not only does she speak fondly about her family, her childhood, her lovers and her most beloved daughter, but of the epoch she belonged to. This fashion designer’s writing is reminiscent of the literary work of Collette and at times of the Hungarian writer, Antal Szerb, for much like them, she is able to stuff that which pathos is built of prettily into a pair of stockings. This is, after all, the same woman who revolutionised the zipper by virtue of making it conspicuous in her 1935 collection of evening dresses. She made pockets in the shape of lips and a shoe sit comfortably upon a head as if it were a hat, and unlike most other designers, believed that imitation is the best form of flattery.

***

Early Sorrows, Danilo Kiš

Kiš is a very well-known writer, and apart from The Encyclopaedia of the Dead, which in my mind is perhaps the closest I have come to reading the most perfect short story, it is the Family Circus trilogy which I find I relate to most, emotionally. Early Sorrows is the first book of that trilogy where we are introduced to the figure of an absent father figure whose spirit embodies and is raised to a myth in all three books. This one, I find the most tender, the ramblings of child whose father had disappeared, whose memories and loss are brought to the reader in the most tangible ways—a missing signature in a child’s report card replaced by a wavy line that represents his father’s tottering gait when the child last saw him. It is clearly a visible absence of fatherhood that fills these robust presences that comprise this first book of the family circus trilogy. I am not familiar with Serbian as a language, but even in translation, I heard the music.

***

Geschwister Tanner, Robert Walser

Translated superbly by Susan Bernofsky into English as The Tanners, this novel was composed in a mere six weeks while Robert Walser was staying with his brother, Karl Walser, in Berlin. It is a novel about siblings, and centers around a protagonist who is unable to be industrious in this world. Walser’s uniqueness, however, lies in his voice, in his unusually strange way of seeing things and to find great wonder in the small. With his writing, one could often miss the point, for it is often visceral and perhaps cannot be perceived by giants. Thomas Mann apparently did not quite understand what all the fuss about Robert Walser was about.

***

Hotel Savoy, Joseph Roth

Roth was a genius and that really shot through in his Radetskymarsch, but here I want to speak of another novel that is equally beautiful. Here, one finds a hotel in a beleaguered war-torn Europe as a sanctuary for the lost, the wounded (literally) for cabaret singers, clowns, imposters and melancholics. Roth, himself spent many of his years in hotels and this novel, like many of his others—teems with his signature melancholic humour and joy. The hotel offers temporary stay and the guests there are temporary, rootless apparitions wedged between the past and the future. If any book by Roth could be likened to the circus and its motley carnival features, it would be Hotel Savoy.

***

Das Schloss, Franz Kafka

The English translation by Mark Harman is probably the closest to Kafka’s original text. Somewhere in the middle of writing this novel, Kafka realised that his first-person narrator could not possibly know all that he was claiming to know. He struck out all the ‘I’s and replaced them with K’s and realised that he did not, as one would expect, need to make many other resultant changes. The earlier drafts of the novel were also more psychologically intelligible but Kafka decided to cut out all those causal links, as well, resulting in what emerges even a century later as a riddle of a novel. In German, the word Schloss (The Castle) also means a lock. This novel reads much like a secret, and like Poe’s Man of the crowd, es laesst sich nicht lesen.

***

The Devil’s Dictionary (Ambrose Bierce)

I have enjoyed reading multiple lexicon novels, especially The Devil’s Dictionary and Milorad Pavic’s Dictionary of the Khazars. Unlike, Pavic, however, Bierce’s entries are much shorter, and clearly one witnesses here, that brevity is the soul of wit. This is the kind of book which you can open on any old page and find yourself stunned at the writer’s most unexpected imagination. As it is a dictionary, Bierce ensures that each individual letter of the alphabet gets its due credence as an individual dictionary entry, and in that connection, I would like to reference my favourite letter of the alphabet:

K: is a consonant that we get from the Greeks, but it can be traced away back beyond them to the Cerathians, a small commercial nation inhabiting the peninsula of Smero. In their tongue it was called Klatch, which means “destroyed.” The form of the letter was originally precisely that of our H, but the erudite Dr. Snedeker explains that it was altered to its present shape to commemorate the destruction of the great temple of Jarute by an earthquake, circa 730 B.C. This building was famous for the two lofty columns of its portico, one of which was broken in half by the catastrophe, the other remaining intact. As the earlier form of the letter is supposed to have been suggested by these pillars, so, it is thought by the great antiquary, its later was adopted as a simple and natural—not to say touching—means of keeping the calamity ever in the national memory. It is not known if the name of the letter was altered as an additional mnemonic, or if the name was always Klatch and the destruction one of nature’s puns. As each theory seems probable enough, I see no objection to believing both—and Dr. Snedeker arrayed himself on that side of the question.

***

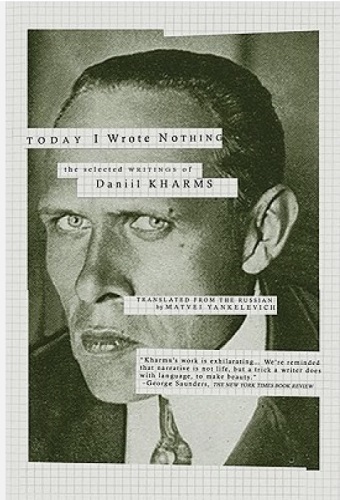

Today I wrote Nothing, Daniil Kharms

This is an English translation of a large collection of Kharms’ fragments, most of which were never published in his own life time. A central section of this book translated so wonderfully by Matvei Yankelevich, is, in fact, a series of mundane, commonplace, bizarre and violent events; not stories, but events, as Kharms entitled them in the original Russian, Sluchai. Kharms was engaging in non-narrative art, where, for instance, a fragment entitled The Meeting, is literally about two people greeting each other on the street, and that is all. Nothing more. Today I wrote nothing is an apt title for writing that wants to erase itself, where the writer aims to delete the subject off the page. In another event, there is a red-headed man who has no eyes or eyes…… By the end of this five-liner, we discover that he has, in fact nothing, so we don’t even know whom we are talking about. We better not talk about him anymore. Kharms was a true genius in both life and art. A man, by and large impoverished, who would deliberately act like an aristocrat in proletariat dives; they arrested him one day, and just like that and no one saw him anymore, like one of the children’s stories he wrote. In writing like this, art precedes experience, much like how the poet, Sebastian in The Tanners is discovered lying dead in the snow in the same way that Robert Walser’s corpse was discovered by little children half a century later.