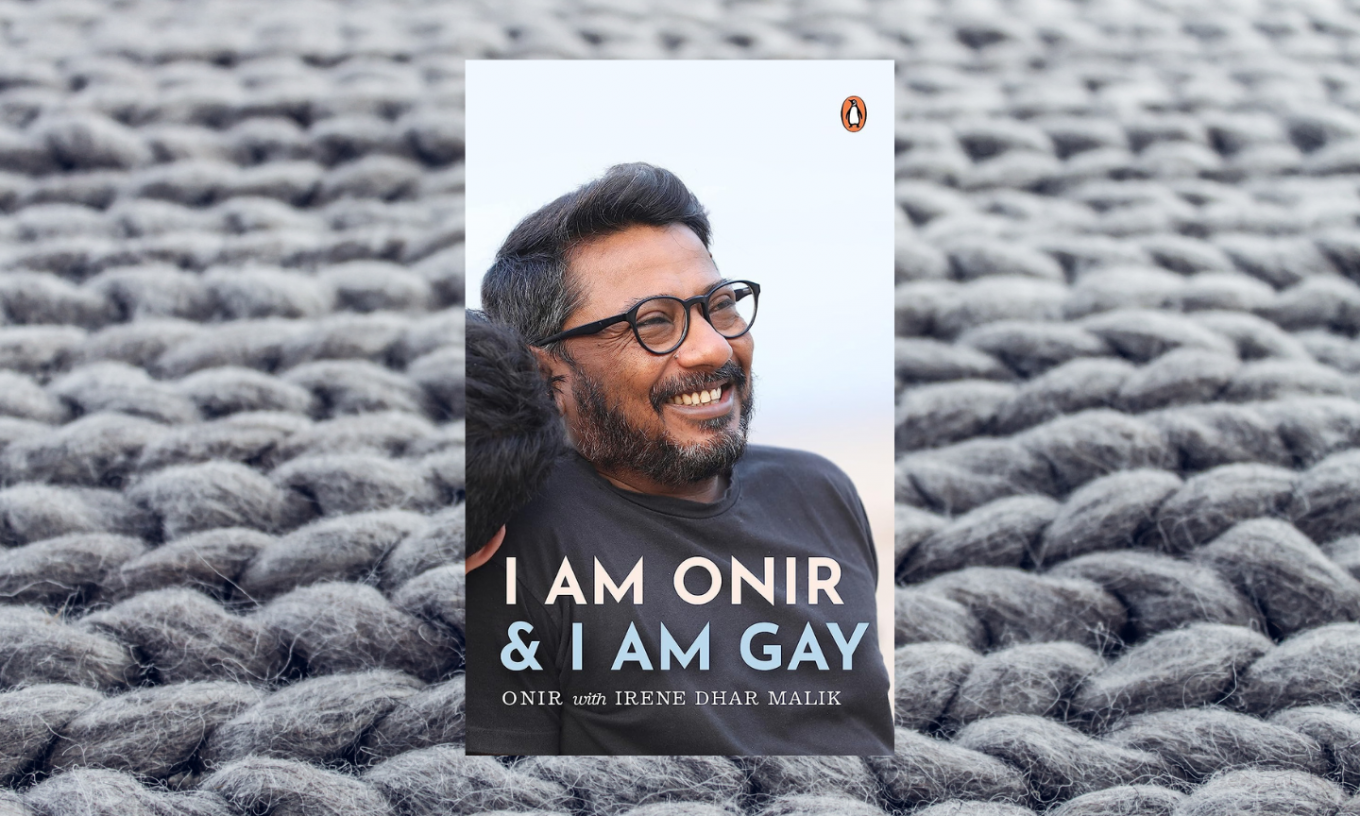

Title: I Am Onir, & I Am Gay

Author: Onir with Irene Dhar Malik

Publisher: Penguin Viking

Year of publication: 2022

The Ownership of Identity

In 2010, the film I Am, directed by Onir, was released. Titles, whether of books or movies, have a visual and an aural quality to them. I Am can be heard as both complete and incomplete, nudging us to watch the bouquet of stories it presents, with expectation as well as conviction. As an assertion, it reinforces existence, presence, being-ness. As a fragment, it begs completion. Who am I? The movie provides the answers. In Onir’s memoir written with his sister Irene Dhar Malik, the title is complete, self-sufficient, assertive. A bold declaration as well as a challenge to those who want to look away. The title – I Am Onir, & I Am Gay –works as a grammatical construct that reflects a journey simultaneously of exploration and arrival, of confidence and self-containment.

The exploration began, perhaps, from the film My Brother Nikhil, Onir’s directorial debut in 2005. The film was inspired by the life of Dominic D’Souza, “the first known HIV-positive case in India”. In 1989, he was “arrested by the Goa police and kept in solitary confinement” (pg 146). Dominic died in 1992. The movie touched a chord with moviegoers and the festival circuit, and it has held its own as a cult film around a difficult and sensitive subject.

2005 was still early days for homosexuality on the big screen. In 2023, it is still early days for serious creative engagement with the subject. Taboos and the closet still dog each entity of the LGBTQIA+ spectrum. Against this background, in the context of a still-homophobic nation, Onir’s memoir rings out loud and clear, a courageous call out to all those still in the shadows, to all those who want to brush aside or completely deny the existence of a section of the population.

The book arrives at this ownership of identity through lanes and by-lanes, sometimes along highways and roads, in an experiential manner, tinged with fear – of losing one’s way, of getting caught and punished for no wrong, of losing those you love, of being misunderstood, maligned, of not being able to tell the stories one wants to. The title slides one aspect of the identity into the other, drawing in their reverberations, making sure that you listen to them simultaneously, not apart from each other. The aural quality of this double assertion is powerful, more so when heard against the background of the roiling contemporary socio-cultural and political landscape we inhabit.

There is rawness of emotion and experience here, an inner and an outer journey, a journey undertaken twice – in the experiencing of it and in the writing through recollection – as is inevitable to the form of the memoir. The collaborative nature of the writing makes it even more challenging, especially so when the collaboration is between siblings.

So, I asked Irene the question:

As a sister and as an individual getting closer to understanding another, what did co-writing this book mean to you?

Irene: I guess co-writing the book was an extension of my big sister act, always staying a part of things that Onir does. We worked out a workflow that involved him writing down stuff and sending them to me when a chunk was ready. And then I’d rewrite, flesh things out, fill in the gaps as I remembered much more as the elder sibling.

The most unexpected part of the writing process was the discovery that there was so much I didn’t know about a person whom I have known so closely. And this is in a really close relationship – it makes me think about how lonely that space must have been. It made me understand why the book is so important as a part of the acceptance that we seek to see around us. It’s not that I couldn’t accept his sexuality, it’s that he was going through things that he could never talk about.

One hopes that the overlapping journeys made through different sensibilities and sensitivities may have helped set demons to rest, overcome traumas, and seek answers to questions – it has a personal aspect to it that is not the subject of this review. What is, of course, is what the book conveys. A clear message, poignant, thought provoking, one that draws in the past and prepares the road to the future:

Imagine growing up in a world where you never heard stories about yourself, where you were never present in a history or a biology class. Never present in cinema or TV apart from being ridiculed with over-the-top caricatures that you could not and did not identify with. Your sense of identity was absent since your childhood. And then, one day you realized that you are the ‘other’. You have to learn to accept yourself. You also have the task of making the world accept you and your love. I always wonder why it is so difficult for the heteronormative world to accept me; I accepted the heteronormative world without any effort. But I suppose I was never given a choice, and they were not aware of me. (pg 259)

Memoirs run the fear of being judged for character rather than for the writing or the ideas. In a filmmaker’s memoir, it is inevitable that the journey will be as much of the anguish and exhilaration of making films as of the angst and bitter-sweetness of the personal. And sometimes they will coincide. This book traces the memoirist’s experience through these dual journeys as someone trying to find his mojo as a filmmaker, telling stories differently, and as an individual grappling with identity both as a filmmaker and as a gay individual. We have the narratives of the films he edits and later, those he directs with all the drama of such ventures – the endless waiting for approvals, the finances, the production and distribution, producers’ woes, the audience, the brickbats and the awards.

These segments of the narrative are often underlined by self-deprecating humor, anecdotes, and the history of how the films were finally made. Readers get a look, up close, at the process from inception to execution and the theatrical release. Sample this:

I wrote the first draft of My Brother Nikhil in fifteen days. I would act like each of the characters and then, as they talked to one another, I would keep writing. I wrote the dialogue draft as the first draft. I have never formally learnt scriptwriting and have no idea about the three-act structure or other technicalities. I know my scripts often have many technical flaws because of that. I write from my soul. I write what I see and hear. While writing My Brother Nikhil, I would at times get so moved by what was happening in the script that I had to take a break to get hold of my emotions. I would think a lot about Dominic* and try to imagine how he must have felt. At that point, I had not got in touch with anyone who knew the real person as I wanted him to remain an inspiration and create Nikhil without being burdened too much by facts. (pg 148)

There is an undertow at work that lends dramatic energy to the memoir in parts. This undertow is of the vision for the kind of films Onir wants to make, films that the country and the industry are not yet ready for. “In spite of the critical success of My Brother Nikhil and the YRF distribution, I wasn’t flooded with work offers. There was radio silence. When I look back now, I know what it meant – homophobia. At that time, I was too busy enjoying the journey to be able to analyse” (pg 180).

This undertow informs both the professional and the personal, and thus, the issue of identity crops up again, one aspect intensifying the other, though both segue into each other to complete the individual. Each contains pathways and cul-de-sacs, and it is enterprise, human connections, and a smattering of luck that finally opens doors to fulfilment. “I always say this and I will keep repeating it: film-making is all about building relationships with people who believe in your skills and conviction and will stand by you in your journey” (pg 144).

Journeys involve the self and others. This memoir presents a large canvas of individuals who stood by, stood in the way, stood up for, and stood with the memoirist. It includes parents and siblings, of course, but also neighbors, teachers, mentors, school and college mates, directors, scriptwriters, editors, musicians, composers, and those loved and lost. It draws patterns of relationships, whether fulfilled or left incomplete, like patterns drawn on moist window panes. However, often the range of characters seems overwhelming, making inroads and dents into the story when they could so clearly have been left out, the narrative tightened, the flow less disturbed.

Memoirs draw from the past, lending themselves to it with a sense of abandon, relying on memory, on lived experiences recalled in tranquility or restlessness. Often, memory creates a patina of distorted time and forms over the past, making recall hazy, sometimes intangible and at others too palpable. Memoirs require distance and engagement simultaneously. It is difficult. In this case, the collaborative approach would work, I believe, both as challenge and benediction. A process such as this holds the possibility of implosion, or of catharsis.

Yes, in a sense the book has been cathartic, Irene says. We talked about some things we’d never talked about, and though those are not a part of the actual book, they were integral to the book writing process.

… And whenever a mother buys the book for her child and tells Onir that the book has made many conversations possible, we do feel a bit of joy.

The perils of love are clearly evoked through various incidents that bring the community into conflict with the law, unfairly, unjustly. It is proof of why we need to engage with the idea of love over a broader spectrum, why we need to understand and engage with the very essence of identity to understand the scope for it, to have clarity.

“There came a time when I started wondering who I actually was – the relentless, restless creature of the night Kamros or the gentle, shy, sensitive workaholic Onir. The boundaries between day and night would merge at times and so would the boundaries between Kamros and Onir. I realized both were me” (pg 127).

To arrive at this realization, Onir and Irene go as far back into the past as possible, as memory will allow the two of them, perhaps one filling the gaps that the other leaves. Where memory is too difficult, poems fill the space, but the reader never gets to see the lover for whom the poems are written. Only a pronoun. You. These poems thread the narrative between the first chapter and the last, leaving behind poignancy that is also the hallmark of Onir’s movies.