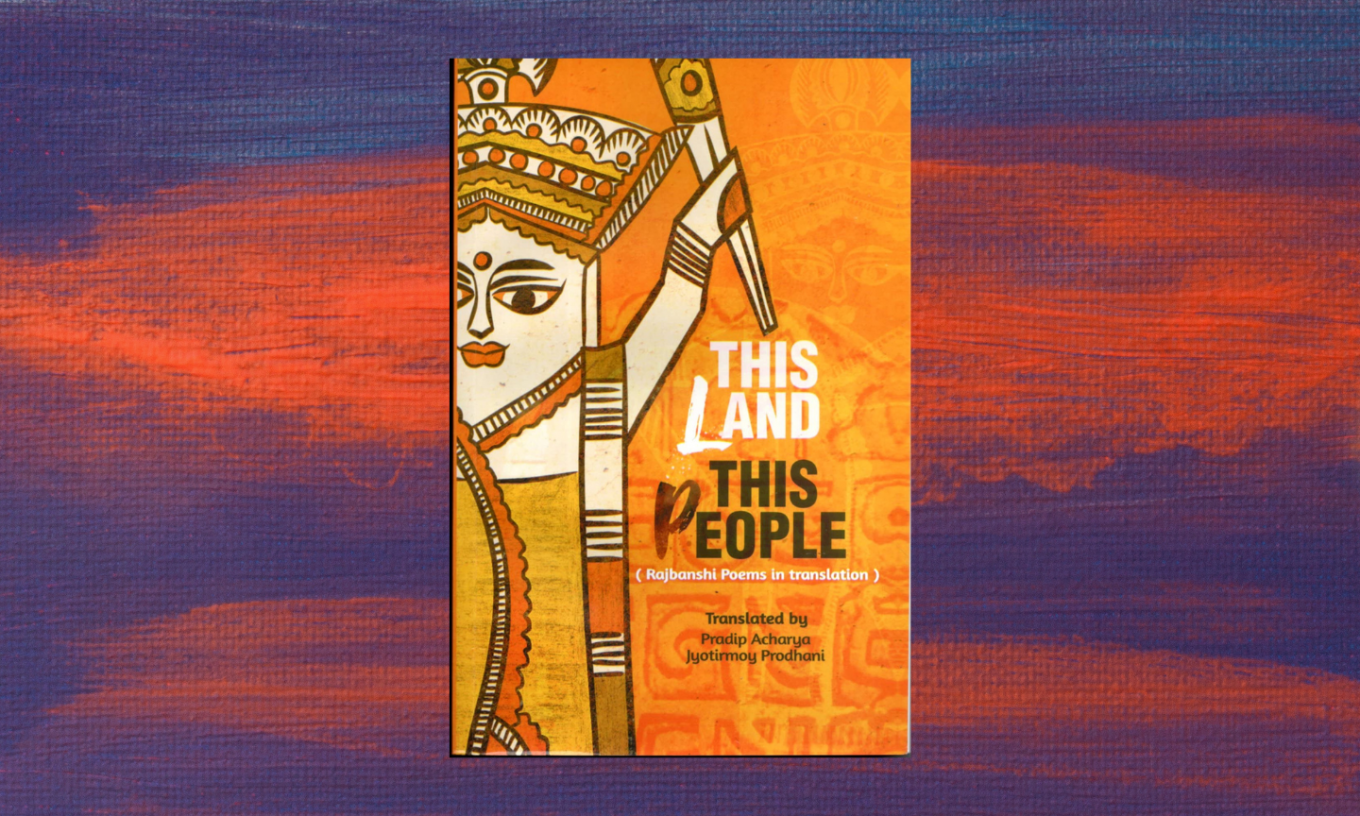

Title: This Land, This People (Rajbanshi Poems in Translation)

Translators: Pradip Acharya, Jyotirmoy Pradhan

Publisher: MRB Publishers, Guwahati

Year of Publication: 2021

Cultural memory is a bond with tenacious strength and it strives to assemble those disassembled across time and space. It seems to find ways of reconfiguring that which is consigned to the past, creating paths for community formation. Poetry has frequently been its vehicle as a mnemonic device evoking personal and community memories, commemorating the past, or bemoaning it nostalgically. Poetry in Indian languages during the period of independence struggle, for example, often deployed synecdochic images of the past glory of the country to claim pride on behalf of it in the present. This way of linking community memories for mobilization purposes and deploying poetry as an instrument for such mobilization is thus a familiar literary trope. The collection of poems edited by Pradip Acharya and Jyotirmoy Pradhan, This Land This People, brings together poems written in the Rajbanshi language (and translated into English in this anthology) in a nationalistic spirit. As we read the text and the paratext of this anthology we learn that most of the poems are occasioned by the respective poet’s love for the Rajbanshi language as well as their desire to be recognized as a distinct community. In this way, identity is at the heart of the thematic of the poems collected in this book.

This anthology does not only present translations of Rajbanshi poems but also is a political statement in itself. Briefly, the book claims Rajbanshi to be a language (not just a dialect of Bengali/Assamese), it asserts the distinctness of the community identity of the Rajbanshi people (variously named by others, but the self-representation by the writers represented here is as Rajbanshi), and strives to introduce to the world the cultural consciousness of the Rajbanshi community. Nearly 50 pages of informative and academic prose is appended situating the Rajbanshi language and literature. A distinctive and remarkable feature of this anthology is that it incorporates poets from three countries – India, Bangladesh, and Nepal – and at least three states of India – Bihar, Bengal and Assam. This fact is indicative of how fragmented and widespread the Rajbanshi-speaking population is and suggests that Rajbanshi poetry crosses several borders – geographical as well as political.

The anthology has translations of a varying number of poems from 73 poets. Most of these poets are made available in English for the first time. It is noteworthy that despite a long tradition of written literature that goes back to the 19th century, and a longer oral tradition, the first anthology to bring together poetry in the Rajbanshi language was as recently as 1996 when Rajbanshi Kabita Sankalan edited by Jatin Barma and Binod Bihari Barman (Anima Prakashani, Kolkata) was published. The present anthology covers several generations of Rajbanshi poets, the earliest being Ratiram Das from the 18th century, Rai Saheb Thakur Panchanan Barma (born 1866) from the 19th century and the most recent being Jagannath Das (born 1987).

The poems collected in this anthology are alive to the identity crisis of the Rajbanshi people and most are vocal about it. If Pratima Barua Pandey (‘The bright mansion smoulders away’) and Rai Saheb Panchanan Barma (‘My menacing mother roars her anger/And rages beyond brandishing the pestle’) prefer metaphorical expression, Tushar Bandopadhyay (“We Still are Aliens”) and Basanta Kumar Das (“Song to Rise”) are upfront in their articulation of Rajbanshi nationalist sentiment. Like Sameer Chattopadhyay in “Awakening”, (‘Darkness has seized the village’) many poets regret the neglect of their culture and language which are nostalgically evoked through diverse forms of memories – geographical, occupational, cultural, performative, or through specific flowers, trees, festivals, and so on. For example, see Alauddin Sarkar’s poem “In this Pushna”:

Gone are the rivers and lakes

That we could go in the dawn

And cast the fishing nets.

To the lessees they have all been sold

By our government so we were told.

Because of this government also gone

The pithas, sweet rice, herbs and fish.

Also gone to the alien land,

Forefather’s rites and rituals, pujas and ceremonies.

Many poems have an elegiac note and it is perhaps not incorrect to read them in an allegorical manner. To cite an instance: Amitabh Ranjan Kanu (‘Like a hearse of sandal wood something smoulders / Inside my smarting heart, / The fire melts into a sea. I drown…’). The poem that has given this anthology its title may be cited here as exemplifying several attitudes found in many poems here:

No I don’t want anything else

The fecund field of my adolescence

The green expanse of emptiness

In the dew cold of a Sunday

The bathing and the unease of the shiver

Yes I want that

The trees and blossom

Where the sajana flowers like earrings

Where the coral blossoms as my beloved

Blowing through the shinda to make the amber sparkle

The adolescent hours stilted onto the emptiness

Give that back to me

I don’t want anything else, not me.

The accumulated weight of the diverse allusions, attitudes, images and invocations in these poems builds a case for asserting the cultural inheritance of the Rajbanshi people. The motif of home whether as nostalgia or as hope seems to be common across these poems. The various individual voices of the poets all seem to converge in the collective quest for identity.

It is a sad commentary on our ignorance that many, like this reviewer, would not have known that there exists a language called Rajbanshi and a community with a distinct culture and a curious history that speak it lovingly. As the march of modernity and its various avatars lead us inexorably toward homogeneity, more and more linguistic communities face the threat of loss of their legacies, and a country famous as a “tree of tongues” begins to be elegiac about its dying languages and their cultures. Against this grim picture, publications such as This Land This People are commendable efforts to fight this trend. Every book that celebrates its little corner in this vast land of diverse cultures and languages is a lamp held against advancing darkness.