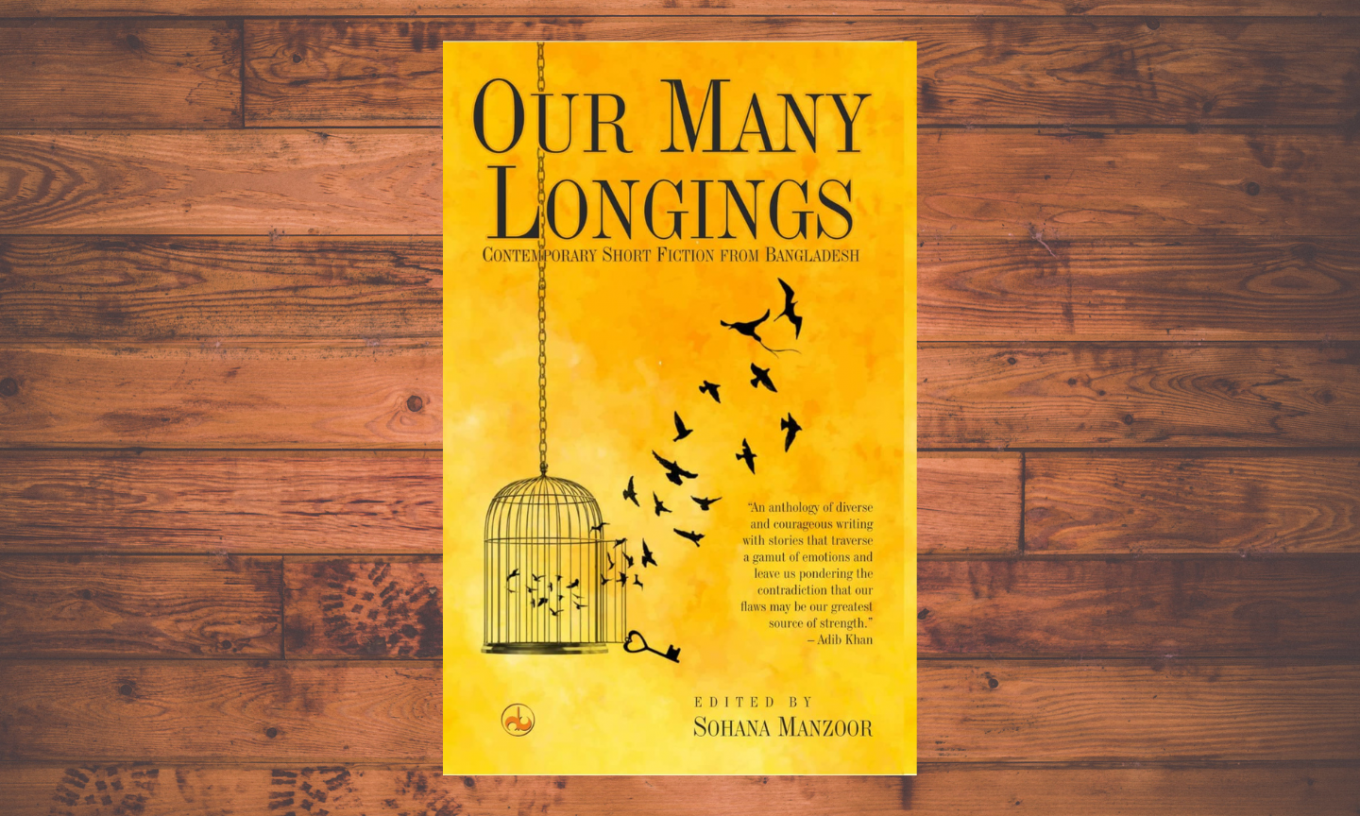

Title: Our Many Longings – Contemporary Short Fiction from Bangladesh

Editor: Sohana Manzoor

Publisher: Dhauli Books

Year of Publication: 2021

Longings and Belongings

The word “longing” is one half of “belonging”, each harking back to the other. Our Many Longings, the title of this anthology, is resonant with this sense of belonging, the longing for it, the identity that belonging creates, the yearning for identity. For a young nation driven by its memory of the recent past, of its struggle against an imposed identity, it is natural that its stories will carry the evocation of history’s bruises, its fears, the rawness of open wounds; that its characters will want to both remember and bandage this wound, and in the process give rise to other questions of identity cutting across nationality, gender, language, as well as personal quests and confusions of daily living. Edited by Sohana Manzoor, published by Dhauli Books, this anthology contains 19 stories variously written in English, translated from Bengali, by writers living in Bangladesh, and by those from the diaspora.

The luxury of taking one’s time to read a book a couple of times of times before reviewing it, is not easily available to all reviewers. Commercial demands drive reviews differently. When one has the luxury and the review is not driven by said commerce, one can slow down and let a book open up its treasures – sometimes all at once and at others, slowly, through tiny revelations that spring up from the pages. And so, when I returned to Our Many Longings a second time, a sentence from the story “Cyclone” written by Khademul Islam seemed to beckon and then hold my hand:

It is the morning after the cyclone. I am ten years old, standing on the front verandah of our house looking down at Momin Road (pg 125).

The sentence is innocuous; the ten-year old narrator will go on to describe the aftermath of a devastating cyclone in Chittagong in 1963. But this natural cyclone that leaves disaster and then calmness in its wake, is the harbinger of another cyclone, more challenging, more life changing – that of the War of Liberation. Like in the beginning, at the end too (forgive the spoiler), the young narrator stands watching – this time the retreating back of the procession of Chittagong Radio artistes collecting funds for Cyclone Relief:

…somewhere at their back is Abhoy, spinning anticlockwise, simmering, churning, seething, roiling, like innumerable other Bengalis gathering within themselves the force that eight short years later would blast East Pakistan loose from its moorings and set it free as Bangladesh (pg. 146).

As a reader, I find myself in this immersive experience: standing at the periphery of a nation, watching it through its stories. The cyclone of war and liberation has passed, leaving behind a new nation as well as the detritus of the old. Out of this churn arise stories around identity, existence, love and its manifold shapes, the starkness of war and what it does to sentient beings, the quality of being humane or its absence.

The book is framed by two stories – “Beauty and the Jinn” by Rahad Abir and “Nuru” by Hasan Al Zayed – that leave one disturbed due to the way they turn the gaze on the self, individually and collectively. The elaborate confessional voice of the first-person narrator in “Beauty and the Jinn” is of the imam of a local mosque who rapes a 11-year-old and threatens her with dire consequences if she snitches on him. The description of what follows – the girl’s physical and emotional trauma, the father’s innocence and helplessness, the imam’s machinations to save himself, and society’s blinkered-ness – is terrifying in its detail and the ugliness of its intent. Zayed’s “Nuru”, also in the first-person, looks inward too, at a collective failure, a collective sense of guilt. Staccato in its movement, the story manages to draw attention to the sense of being human and humane.

Identity is intrinsic to being human. In the 17 stories between these bookends, we see this constant churn of belonging: to name, nation, language, gender. It is a flux that binds the stories. In “Light”, the character’s name is Pradip (lamp that gives light). Living and working in Bahrain, he finds his name changed to Rafiq:

an Arabic name that connotes the very mundane: attendant, friend, buddy, mate, fellow and other equally pedantic words. …Pradip is not a lonely sufferer of such a fate here. …in Bahrain, all underprivileged men from South Asia are addressed as Rafiq (pg. 53).

In “Frank and Frida”, Farida finds herself in a similar situation in New York, but instead of the expected angst at the mutation of her name from Farida to Frida, she carves her own unique identity, with a sense of inner security that accentuates the insecurity of the self in those who have lived longer in the country, who belong to it as she does not. There are those who would exoticize her identity, seeking magic and mystique that she denies, bringing instead, to her interaction with them, a sense of the self, suffused with an inherent sensuality that is seemingly more confident than theirs.

Name and language, two planes of selfhood, segue from one to the other across the pages. The narratives, in most cases, are pared down, devoid of excess and ornamentation, of sentimentality and melodrama. “The Green Passport” by Shaheen Akhtar (translated by Arifa Ghani Rahman) explores the plight of the Bihari Muslim in Bangladesh. Having supported the Pakistani army against the Mukti Bahini, these people find themselves in no-man’s land – neither accepted by Bangladesh nor welcome in Pakistan. Sultan Ahmed and his grandfather Rahamatullah spar over their sense of nation and allegiance, their freedom to use Urdu; the old man hankers for the haloed ground of his ancestors in Bihar but is unable to leave the land where his son died during the War of Liberation. The green passport is Ahmed’s escape to linguistic freedom in India that his grandfather doesn’t believe in.

In “Without a Name, Without a Tribe”, a man returns to his home town in the midst of the war and watches the brutal murder of a stranger by Pakistani soldiers. The starkness of war, of hatred, is projected through the cityscape, its eerie darkness and silence broken by the sound of boots and the horrific sight that unfolds before him. The claustrophobia of this city almost under siege, petrified into silence, builds up to the last frenzied act, compelling in the nightmare it unearths.

Perhaps one of the most searing stories in the selection is “Torso” by Afsan Chowdhury (translated by Shamsad Mortuza). Malati has to cremate her husband, killed in the war, but his head has been severed from his torso. Rummaging in the pile of heads and bodies at the PTI building where both Hindus and Muslims have been slaughtered, she finds his head and then a torso that she thinks belongs to him. As she drags the two in a sack along rain-beaten streets in the dark, she is confronted by a group of men who want her to prove her religion. Identity tapers down to the corpse’s phallus – religious machoism, marital claim, war, children’s innocence boils down to this one moment, one bodily part. The ironical end is terrifying in its implication of human nature, of the tragedy of war, of the arbitrariness of life.

Violence is inherent to the story, in its title, in the deliberate choice of a journalistic tone, yet limned with softness, by grit, determination, and that most liberating literary impulse, compassion. The translation is powerful, retaining the tone and essence of the original, the emotion held in, taut.

The short story, by the very nature of its genre, is an apt frame within which to embed momentous feelings, the unexpressed continuity of histories, the implications and nuances of open endings. The stories in Our Many Longings seem to have been chosen carefully to bring together the full extent of what the short story does to our experiences – those that drive the story and which the story allows to extend beyond the page. These stories, as short fiction does, take up a large canvas of experience and sharpen it down to individual moments and individual histories whether of the bhasha andolan and the eventual war of liberation or gendered and class conflicts.

In Tahmima Anam’s “Mother’s Milk”, the death and burial of a young bull brings liberation for a young mother, whose new-born son died at her breasts. “I was only asleep for a minute,” she says, “but when I opened my eyes, he was blue.” She has had no closure, no time to name the baby, and as mother and woman, she carries the burden of blame, guilt and sorrow. The story ends with the possibility of liberation, the possibility of how this story of guilt and sorrow can be altered, paving the way to a new narrative for her.

*

Rape as political weapon is an abhorrent truism, whether inside the house or out of it. Wartime sexual violence in Bangladesh created a category of victims of rape and abuse who were later given the title of biranganas by the country’s government. Published in a year that celebrates 50 years of independence, it is surprising that Our Many Longings has no story about these women who faced the brunt of the War of Liberation. The book is an amalgamation of stories from across the spectrum: those written in English; those in translation; those by writers from the diaspora, by writers born before the country was born and after. The anthology is held together by the collective notion of nation and identity, so one wonders – why are these narratives missing from the selection? Is it due to an absence of stories or the unavailability of translations?

Despite this lacuna, which is perhaps more in my mind as a reviewer than a reflection of the editor’s choice, Our Many Longings gives to us – especially to those not familiar with Bangladeshi literature, or its rich heritage of the short form – a cornucopia of contemporary writing from the country. In a singularly important year of celebration, this compilation published by an independent Indian publisher, is in many ways, an ideal gift.