Title: After Grief

Author: Shikhandin

Publisher: Red River

Year of Publication: August 2021

Location. Movement. Stasis. Volition. These are states of mind, the whereabouts of being held in an emotion, marking time before the next step. In the roster of emotional flux and stasis, grief, perhaps, impels the sense of whereabouts with a larger magnitude than other emotions, taking its time to find its bearings. It asks of us, again and again, where am I? and the question demands answers, for it to release us from darkness. In Shikhandin’s book of poems After Grief, published by Red River in 2021, this journey begins at the point of loss, pain, absence, and progresses gradually, through gnawing experience, to rise out of it and into joyful, infectious laughter that is relayed from one to another, displacement completed of one’s volition, the curtain dropping over an act.

These poems dive deep into the abyss of grief, into each lived realization of it, its exploration vignette-like, the poet a throbbing presence in the face of different kinds of loss – of a person, of nature, of an emotion, a presence.

Death is violent, implosive, “the unacceptable birthing of void,” an absence with many names and synonyms, many iterations, trajectories of effect and affect. Grief arises out of this loss, of someone’s passing; grief is memory of what was or was not, of an emotional absence; grief is about the memory of this absence, “a slow release drug”.

In ‘Beads’, one of the most evocative poems in the collection, rich in imagery and heavy with the sense of the pandemic’s presence, the counting of prayer beads (japamala) brings not solace but a reminder of the relentless melting of time, of its falling away and scattering. The poem begins with the image of a japamala “clasped” in the hand; it ends with the image of the broken mala, the beads tumbling, each a snowflake of time melting in the sun. It acknowledges time’s unobstructed march, the human helplessness within it, and the courage that “dare(s) to make music out of the crush and grind of the falling beads.”

It is this courage that eventually gives rise to laughter, but that destination is at a distance yet, and so, one must walk the terrain of grief, tracing and retracing steps in the mind and heart – in the poems, the journey piles up images, the rubble of lived anguish, but with surgical precision and intent, till they coalesce into a collective image that draws all iterations into itself.

So, wind bears static

So, silence is static

So, protest is static

minced fine and kneaded

Into fantastic shapes, gift wrapped

and exchanged with hugs and smiles

So, unto death, the library of silences.

(Threnody, p. 15)

And then we arrive at the almost aphoristic ‘Immortality’, a pause after the breathless fall and tumble and despair of the preceding poems.

Riptides have expiry dates.

Earthquakes finally subside.

Abysses close. Mountains erode.

what remains eternal

lies in the final settlement. And that rests

in your own fragile hands.

Don’t drop them.

(p. 17)

***

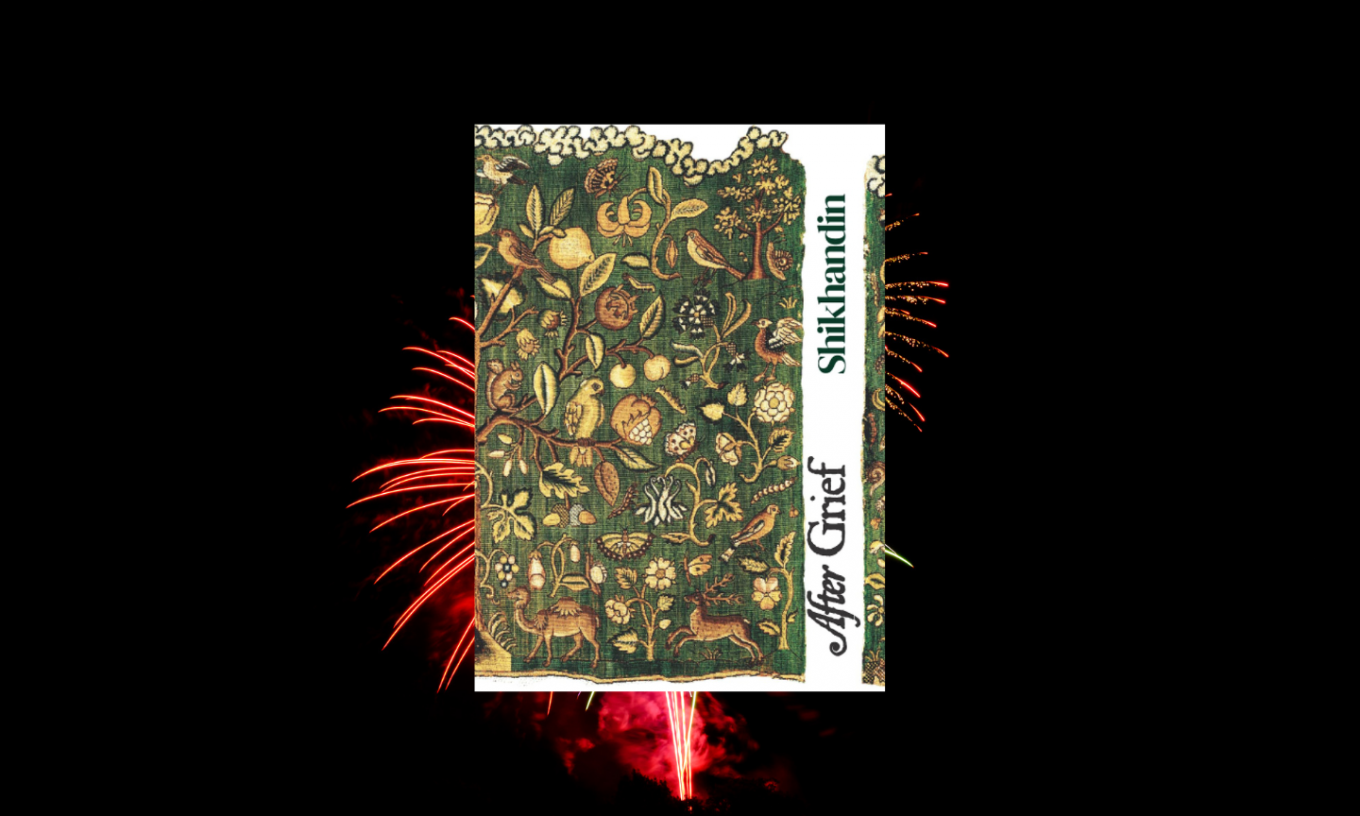

Reading this collection by Shikhandin is a journey in exploring grief and the slow withdrawal from this darkness into light and communion, and therefore, it is significant that it is titled After Grief, promising restoration, replenishment, life. The book cover is a part of this journey, the book’s tryst with this promise, with poetry itself.

My first instinct was to use the painting of Ophelia by John Everett Millais, says Dibyajyoti Sarma of Red River. Then I saw this image of a tapestry depicting the tree of life, which I thought was perfect. For while the book is about grief, it is also about life, the living.

In a classic case of a book cover determining how a narrative resolves itself, Shikhandin added the last poem, ‘Laughter’, after she saw the image. It was inspired by Dibyajyoti’s cover, because it is so joyous, she says. Life is not only about grief. There is something called after grief. Where do we go after grief? Humanity needs to laugh. There is joy at the end of grief.

The cover changed how the book ended, the heaviness gave way to life and living, to laughter, to the coming together of people, till the laughter resonates from “pond to lake to stream, hamlets, forests, deserts and mountains, to vapour rising up to the clouds…”

… And, the stars will catch them

at night and send them spinning to the moon.

And moon will toss them over to the sun. And the sun will rain

them down on Earth. And everywhere humans will lift up

their faces, arch their throats, and open wide

their mouths.

(“Laughter”. p. 74)

The image draws into its whorls and curlicues, in the leap of the deer and in the imagined song of birds, the emotions of the poems inside, the sense of constant movement.

The journey, though, is demanding – it requires the mind to cull and remember moments that one would rather push under the carpet, banish into hidden, dark corners. Some of the most difficult poems in terms of this movement belong to Parts IV and V of the book. These are intimate poems, poems of struggle, images segueing from one difficult, deepening emotion into another, groping to understand what was, emotions recollected as well as lived, and thus, more layered in trying to understand the mother-daughter relationship as well as the traces it has left behind. These poems are complex in their emotional weave, tangling and disentangling the skeins of the desire for affection and finding in its place the memory of its absence. Here, the poems are connected by memory and its “bones”, imagination fills the spaces of a child’s remembered yearning for her mother’s affection, the adult’s bitter recalling of what was not, followed by the slow laying-to-rest, the word-images shifting from poem to poem, from “rage-cindered… quartz”, to “the fist that slammed out through your vagina” to “My forehead burnt with the history we are counselled to forget” to, finally, “tides on a shore./ Nothing less nothing more” (pp 48-59).

The wholesomeness of grief, its outpouring, questioning, flowing, is replaced first with the tightness of forbearance, of not wanting to give in, keeping memory intact (Section IV) to finally the process of leaving grief behind. These two sections are the most personal, the grief in-the-mind and on-the-body, grief for an always-absent whose passing is less painful perhaps than its being.

Between ‘The Way I Imagined You’ (pg 45) and ‘If You Wish to Mourn Me’ (pg 60), the poet rides part of an arc – of memory and retrieval, of grief and its turbulence, of slow quietening, then, the arching towards a semblance of restfulness.

Section VI begins with her dissenting tribute to Emily Dickinson, ‘Dear Emily I Disagree’.

You perceived the outside view

You saw through

The constructed mysteries, the mocking cipher

Yet you chose to call Death a carriage driver?

Death who comes not again and again

but is indeed the entire moving train…

(pg 64)

***

“Somethings cannot be hurried,” Shikhandin writes in the Afterword. “They move by their own will, and at their own pace, in their own time.” As does grief, and poetry. The passing of grief, from threnody to laughter, is momentous – it leaves behind lingering echoes and remnants at first, to be slowly replaced with the tempo and rising volume of laughter passed on from mouth to mouth, heart to heart.

Poetry demands that we smash through the parameters of necessity and form, and so, though the editor in me feels tempted to comment on the need for brevity in certain lines, on tighter editing for a couple of poems here and there, that, I am aware, would be akin to nit-picking.

With divisiveness and hatred seeking a new norm every day, and with the pandemic’s long, devastating march through our lives, this collective laughter is what we urgently need in order to purge, to cleanse, to keep our tryst with happiness and living.

And hearts

will raise a tsunami of happy sounds

so united that it will be indistinguishable from a single note,

and will generously fill the hollow

places where human sorrows love to sit.

…

Let me begin then, hah hah ha. Now you take it

forward. To hee hee hee. To hoh hoh ho

and heh heh heh. And all the variations in between…

(pg. 74)