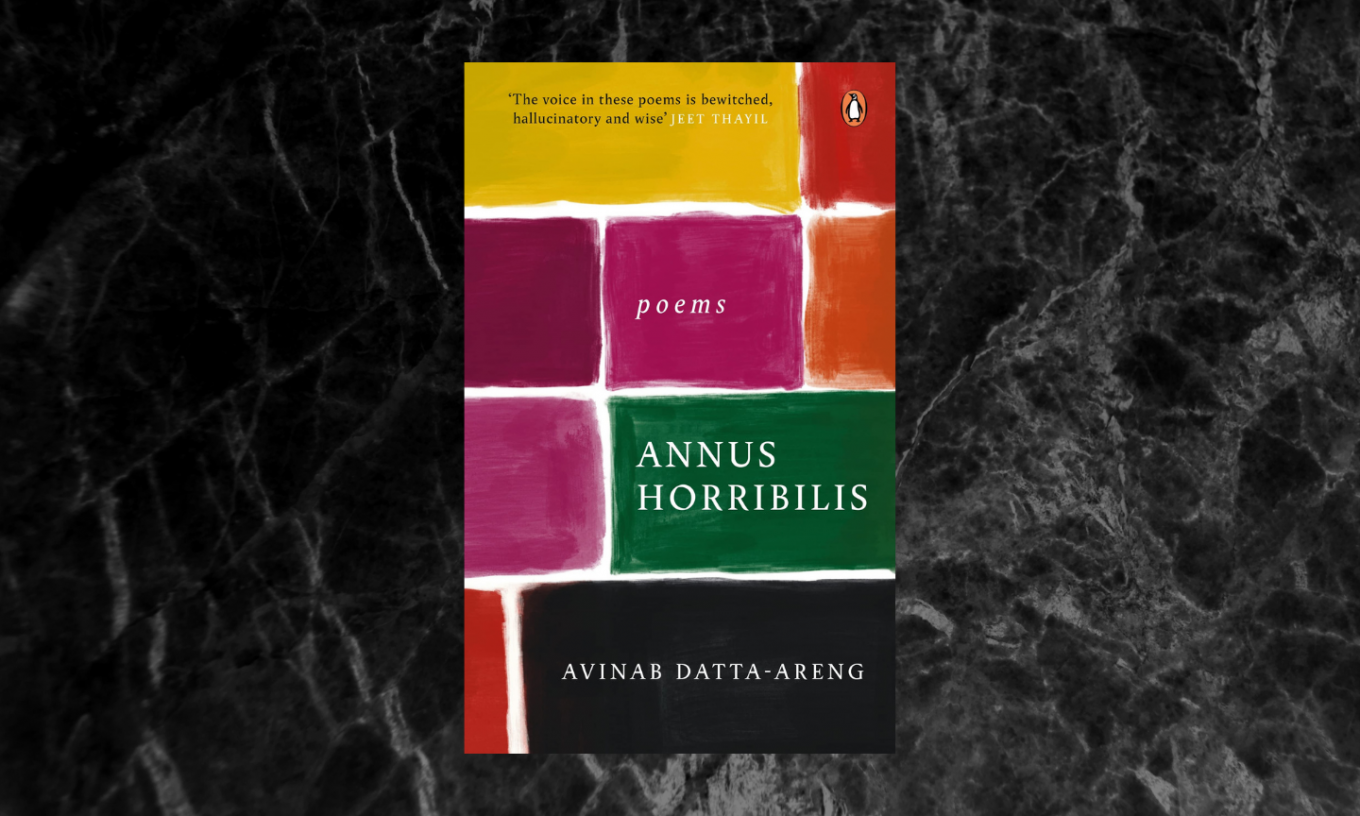

Avinab Datta-Areng is out with his first book of poems, Annus Horribilis from Penguin. He feels that writing the book gave him a sense of ‘place’ and an understanding of where he belongs in life, says the poet, for whom movement has been a long constant. Elsewhere, Areng has often spoken about the influence of music in his life, but says that this book became, a search for a language in which thought might survive and perhaps even reach out towards others. Avinab has previously been a recipient of the Charles Pick fellowship and the Vijay Nambisan fellowship. He also edits the literary magazine Nether. In this interview, The Bangalore Review talks to him about his poetry, influences, relationships and more.

‘When he stopped, hearing

footsteps, I shrank into

a cigarette, into the grace

of one’s own unbearable

ghost, and when he turned—

he did that only once,

before disappearing

into his slum—terrified,

I ordered him to run’ (The Drunk)

TBR: One often gets the feeling that these poems are addressed or written for an alternate self, a dream for a dreamer where sunflowers don’t exist. Take us through the journey of writing, of finding poetry, of surviving loss and resurrection through pain.

Avinab: If I try to look back at my writing journey, emotionally, there was always a sense of secrecy and hiding. When I started writing and for the longest time, I was afraid of telling anyone or was not comfortable telling anyone that I wrote, it was my secret life and where I hid (but to me it was always where my real life was, I was unfortunately sure of that very early on). I didn’t see any other way. As for finding poetry, in a serious way, it came through a natural progression from music and lyrics. When I was much younger I always wanted to be a musician, and my notebooks would be full of lyrics for songs, but at the same time I was intensely afraid of the world, of people, of performance, so which is probably why I never instinctively quite ended up pursuing music seriously. This is when I started reading poetry, writing poems and, I suspect, realized that the demands and ways of poetry allowed me the tools to try and understand the living and non-living world (from the relative safety and privacy of my space. read: hiding place). As for the rest of personal histories and the world at large – loss, pain, resurrection, the works – I guess we all have to negotiate what we inherit in our own ways.

‘On the most beautiful morning you will walk out of your house

looking for something true and pure, like a bird bathing.

You will find a bird bathing in a blue puddle.

This is it, you will say to yourself.

This is it, the voice will say to you.

You asked for it and it came.

The powder in its wings spreading that cool,

familiar terror across your shoulders again. It will begin again.

And you should be grateful you can feel it.’ (Report)

TBR: Traces of terror, as it seeps into your day-to-day innocence of living. Your poems often feel as if, living and being alive were in itself one of the most heroic of acts. Tell us then, how your life defines your poetry.

Avinab: That’s a beautiful way of putting it. Isn’t going on, choosing to stay, in and with the world, participating in it, a heroic act? My life is inextricably linked to anything I work on, or at least that’s what I’ve led myself to believe; in some cases, it is the better outcome of me, at least in thought. Sometimes it’s a negotiation of failures, fears, dreams, often a frantic signal to the self and the world. But to be honest, one never really knows for sure. These are just words, a smokescreen. Poetry at least feels up to the task of this flicker, of trying to harness this flicker.

‘She touches your hand as if reaching out

for the jar of falling rain beside her birth’ (Fever, Mother)

TBR: The lines are symbiotic of the tenderness that one can feel throughout the book at the mention of your mother. Could you tell us about how your mother becomes a recurring emotion in your poems?

Avinab: I think I have answered this somewhere else as well. The mother is a central theme of my work, and it’s something I’ve noticed myself along the way. The mother’s life or affliction or truth is something that I’ve considered, painfully, to be the source of my process and the reason for the continuity of the larger world. It’s a kind of myth-making, obviously. There are certain key incidents in her life that represent, for me, a silencing, a rupture, but that silencing is also something upon which speech, beauty, everything in the world is composed, because she allows it. To think of it, my ideas of the mother are also probably, historically, somehow embedded in our culture, and I am merely experiencing it anew through the prism of the particular mother, her life, experiences, being witness to it, trying to make sense of it.

TBR: Much of your poems, circle around nature and birds in particular. But unlike those who write about nature in their work, you use references from nature, to highlight the starkness of a situation in the most detailed manner possible. Tell us about your relationship with nature as a poet and how it enables your poetry.

Avinab: I feel if I could fully comprehend my relationship with nature or understand how it enables my poetry or influences it – then I would never write anymore, would not feel the need to write, and I would be absolutely content with that outcome.