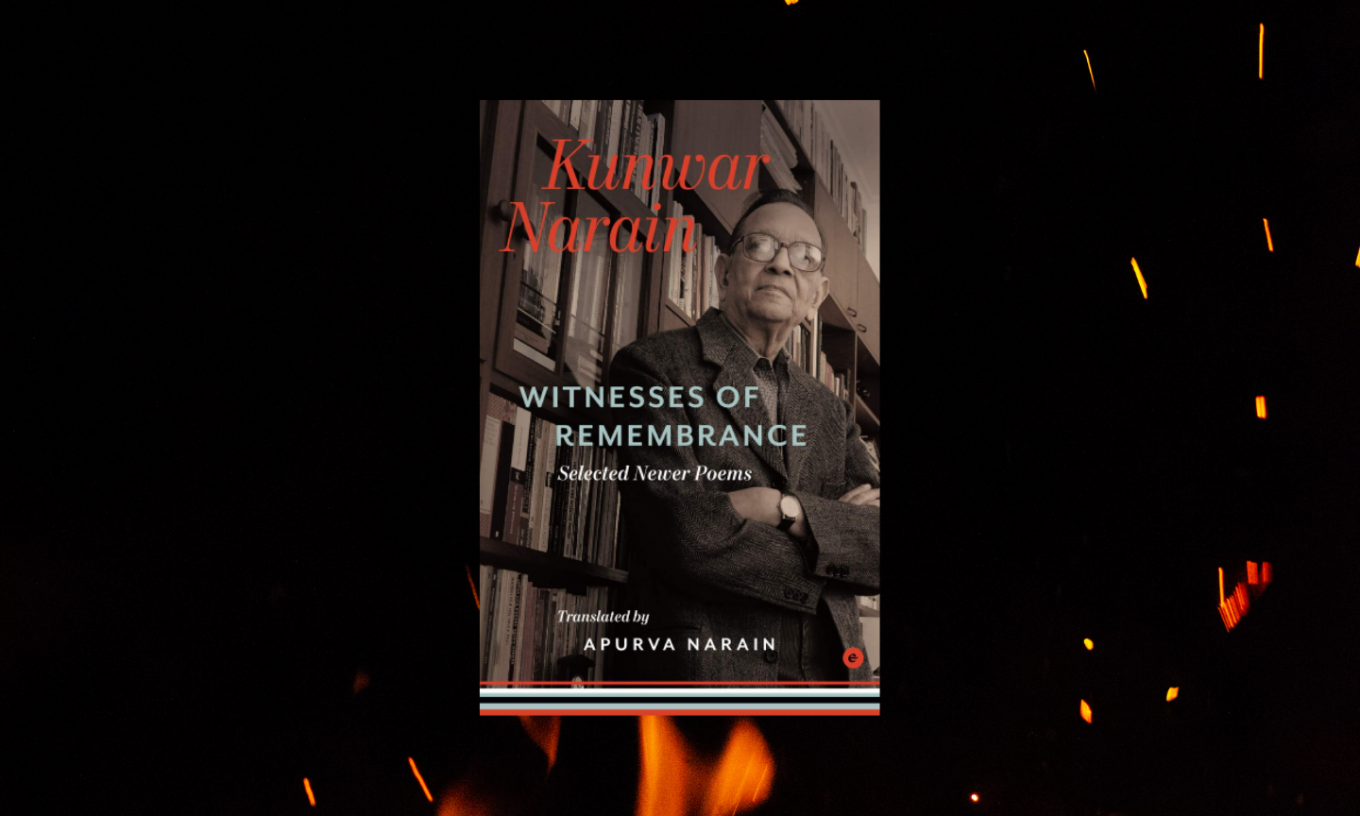

Witnesses of Remembrance – Selected Newer Poems

Kunwar Narain (Translated by Apurva Narain)

Eka (Westland Publications Pvt Ltd), India; 304pp; Poetry

… And a calm repose that sometimes extends all the way to peace…*

As I write this, war rages in Ukraine, a land under siege…

As I write this, Westland Books is wrapping up…

As I write this, it’s a year since this book was published…

***

It’s no coincidence that Witnesses of Remembrance is one of the three books of poetry that I have read in succession, that refer to the word ‘witness’. Poetry, at its pith, is witness, embedded in the poetic vision and voice, in its images. This is what I thought when I first opened the book to a random page and read “A Peaceful War” (“Ek Shaant Yuddh”). That was last year, with the pandemic inside our homes. A year since then, we are in the midst of a different horror, this time one that arises in the minds of men and women, imperialistic, reckless, avaricious.

I read the poem again. Its meticulous and steadfast tone of reason, the casual tenor, belies its internal contradictions – the mood of calm, of a star-splintered night sky draws attention to one half of the title, the oxymoron of the other half delayed, stalled, just as sound is stalled in a war muted on television. We are, all, witnesses to this

complete tale of false ‘n’ true

seen on a screen: the verbatim blow-by-blow account

of a war in the gulf

reported by trusted sources (p. 35).

In the introduction to the book, Apurva Narain writes: “…these poems… have lived his life as much as their own life and afterlife. Mixed with their remembrances are the poet’s memories of his world, my memories of him and, dare I say, perhaps some of your memories of your worlds. For what begins as a personal response to internalized experience can beget much more; experiences worth remembering, in a sense, include the experiences of others” (p. xii).

This book has had a journey of its own, from conception to this point when much water has flowed under the bridge, witnessing the tangles and disentanglements of the world around it, gathering into itself the memories of the past and the lived-ness of the unravelling present. Sitting within this uncertainty, this quickly shifting sand beneath our feet, I find the apparent simplicity of the poet’s words looping out from personal memory and response to the vast external, into a deeper engagement with it.

Consider this closing stanza from ‘Guernica’, the ekphrastic response reaching beyond to draw in the world, its culpability:

All in all

the unquiet picture that emerged

from the peril of an apocalypse

could always be

of a being

and also of a world.

(pg. 9)

***

Elegantly translated by Apurva Narain, the poems (between 1979 and 2018) in this collection are written simply, seemingly un-crafted, consciously kept clean of artifice and ornament. It is the vast, deep resonance of the poetic response that gives them their sonority, the sense of something still to be plucked from within the words, the lines, their gaps – a search for the reader into the poet’s still-witnessing mind. The translation stays true to this core.

Witnesses of Remembrance includes the original poems in Hindi along with their translations. To have within a book the original as well as the translation is a gift that allows one to look simultaneously into the minds of two creators, follow two creative processes. The poet’s witness is a multi-layered experience – translating and imbuing the experiences of other people, simultaneously engaging with the self and the world, cocooned in an inner world, throbbing as it reaches out, quietening again in conversation with the self.

It is tempting to stay with the original, but the translation holds its own in tone and that subtle shift that makes a deeper cut. What is poetry if it cannot wound as well as salve? Often, the shift is simple, unobtrusive, as in “The Pandemic of Numbers” (आंकड़ों की बीमारी), from the first person in the original to the third person in the translation, rendering the contemporary palpable and urgent. The word “pandemic” (बीमारी is less frightening, more personal) raises the poem out of memory into current reality.

Poetry is prophecy, and this diffusion into contemporaneity is often chilling.

Mega Truth/ महासच

…

Now, to find the truth you’ll

not need a mind or idyll,

it’ll find you anywhere

using myriad means, it’ll enter

your home straight away, it’ll play

with your children and grow up

with them, in front of it

the whole world will feel small.

That truth will be

a giant machine, an assembly

of countless circling cogs.

This is the poem to tell our children perhaps, the poem about truth being made and re-made every day. Yet, there is also hope:

An Evening in Golconda/ गोलकुंडा की एक शाम

Removed from the histories

of battles and igniting explosives

there is also a third history

of reconciliations

between the bidis of Rahmat Ali Shah

and the matchsticks of Matsa Raj.

(pg. 79)

Sliding effortlessly from one era to another, one kind of struggle to another, the poet brings on to the same plane the basic human condition – the need to stay alive, to make ends meet, to stay ‘brave’ in the face of daily challenges. There is a subtext of restorative calm running through the poems, even in those that remember restlessness and disquiet, as if there is no other way, as if this restoration to a forgotten state of being, a deep connect with nature, is the only possible answer to present perils.

The poems merge worlds, epochs, situations, universes, juxtapose often contradictory realities before tapering down to simple truths. They find their way through history, memory, time, ecology. Remembering and witnessing this remembrance is a journey that grows into the realization, again and again, of immersion, of nondualism; it limns the movement of the poems in this collection – from remembering to witnessing this internal growth, from the wound of the stone where the sculptor strikes (“The Being of Stones”) to the ‘final note… that doesn’t bind’ (“Raga Bhatiyali).

The Wish of a Leaf

Sitting in a park

I felt at peace

in the comfort of a tree’s shade

I felt at peace

a leaf fell from a twig,

the wish of a leaf

‘now let us leave…’

Contemplating this

I felt at peace

Whether he contemplates the ruins of Golconda or meets Pablo Neruda and Nazim Hikmet, sits under a tree or grapples with the passing of time, this reconciliation with the universe, the constant turning inwards and reaching out, is an inner conversation that is not only the creative process at work but also a condition to be wished for, though not always guaranteed. It is a state of being, ‘desultory/ like the fleeting winds of dawn/ momentary/ like gleaming dewdrops on flowers/ … a poet’s dream beyond touch…’ The dream leaves behind its traces, palpable yet gossamer, fluttering at the threshold.

As I turn the pages again and read some of the poems, I come away with a sense of the passing moment, when the world teeters on the edge, when citizens write their own stories, blinking back fear, when a woman stands on a street, placing sunflower seeds in the enemy’s hands.

Hesitation/ असमंजस

it is possible that this is not

a time of today

but of sometime long before us

and there

where we must reach tomorrow

little children are waiting for us

with bated breath

to see what our epoch

brings for them after all…

With today’s newspaper in one hand

and poems in the other

I hesitate

should I first read to them the news

or the poems…

(pg. 107)