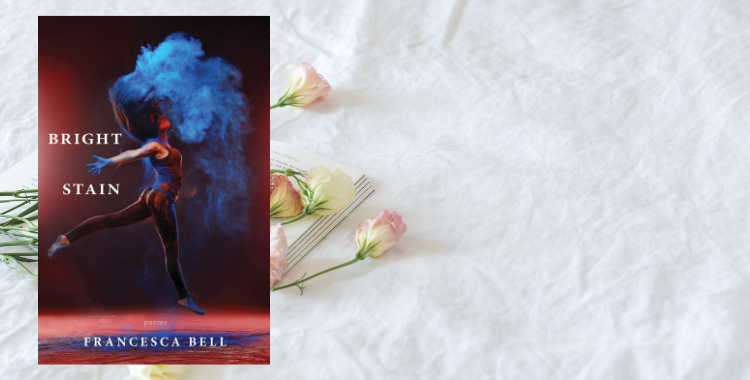

As the title suggests, Francesca Bell’s debut collection of poetry, Bright Stain (Red Hen Press, 2019) is rife with complexity and nuance. A stain might be bright, perhaps beautiful, yet it is also an emblem of error, wound, or stigma. The poems in this text often address the convoluted powers and vulnerabilities of gender. With straightforward storytelling and exquisite diction, conflicted attitudes toward sex and violence are unveiled. Often, Bell’s speaker is a persona—the daughter of an evangelical preacher or a convict. In every case, no judgement is cast. Whatever reprehensible actions are taken, they are detailed with a cool hand. We see the corners of the speakers’ minds, what compels them, their rationalizations, and odd logic.

Consider the poem in which the book’s title is embedded, “Benediction,” written in a persona:

He doesn’t want to relive

what he did to get in here,

freedom sure to come

only with a rough sheet

pulled over his face.

He keeps busy as he can,

works for one dollar a day

in the prison factory,

piecing together mattresses

for college dorm rooms.

He blesses each narrow bed,

thinks of first times

away from home.

Of home. Of new bodies

cushioned by the labor

of his hands, stretched there

and yearning. May there be

ample room for them.

May each loss leave

only the bright stain

of a new beginning.

The opening lines, although clear, are obscure enough to allow the reader to piece together the facts, as the speaker pieces together both the beds, and also the imagined lives of others. The narrator is a convict whose actions were heinous enough to warrant a life sentence. Furthermore, the first four lines imply this prisoner is coping, regulating his behaviour and mind, exercising a control he evidently was unable to exercise in his previous life. This man knows how to slow down, to concentrate, to contemplate. He lives in his minutes and hours, perceives a kind of parallel life: as he constructs mattresses for college dorms, he daydreams a collegiate experience that was, perhaps, not readily available to him. He knows, however, that in every existence there are losses, passions. On the beds he pieces together, young women will lose their virginity, perhaps be violated. Young men will lose their innocence, their sperm. Every act, as his own youthful acts, will leave a “bright stain.”

The poem has a comforting meter, much of it iambic. Each line carries a discreteness such that the poem can be read backward and still retain much of its cohesion. Written in a column, the indentation of every second line recalls the stability of couplets, but disturbed and unbroken by the relief of white space between stanzas. The title, “Benediction,” reinforces the complexity of a poem in the voice of a violent criminal who has learned to bless the beds of coeds living a life he will never know.

For those who love binary judgements about crime, rape, religion, or sexuality, this book will not satisfy. A female persona in this volume is fingered by a killer, yet does not demur, but rather, like the aforementioned convict, merely engages in a revelatory contemplation. Like a memory resurfacing, a rapist recalls the blood of his penetration as he watches, years later, his baby’s head as it crowns. Without condoning the wrongdoing, the poem hints at the humanity in each persona. Thus, we are startled into an ineffable discovery. This is the power of poetry: to unite worlds and spark comprehension if not compassion. And this is the power of a strong image: to embody an idea and transmit it viscerally.

Jane Hirshfield titled one of her books Each Happiness Ringed by Lions. Many of the poems in Bright Stain evince the kind of complexity inherent in that title. In one of the final poems, “And Then,” Bell’s speaker describes love making— after a long dry spell—with a lover or husband:

the man remembers your body,

remembers to love you again,

flicks you like a switch

waiting, ready

in the room’s shadows.

Loneliness from each

reclaimed centimeter,

a humiliating eagerness

rushing you like a hound

loosed in woods, your cry

like baying or keening,

months of waiting become sound.

After the man sleeps, peaceful,

but you are a door he’s opened,

a path grown over now beaten

back down You feel his life,

which will end before yours,

slide slowly away into the dark.

How vividly this interlude is depicted, the “humiliating eagerness,” the speaker “opened” like a door. The repetition of” remembers” in the opening recalls the murky relationship between memory and the urgency of connection, love, and sex— the way, in the first days and months of a relationship, a bonding template is created to which one returns like an animal to a watering hole. Female sexuality is so finely drawn here, how we can be “flicked like a switch,” and relationships, too, are vividly depicted, their periods of ambivalence and quickening. But most importantly, the poem revisits the archtypal and Shakespearean connection of sex and death, this mortal reality which, since Orpheus, has been poetry’s great subject.

Although Bell has been publishing hard hitting, visceral poetry for the last decade, seeing them together in this first collection is to witness the debut of an important voice. Like Kim Addonizio, Sharon Olds, and Dorianne Laux—voices exploring uncharted expanses in the psycho-social realm—this poet occupies a distinctive position in the pantheon of gutsy American poets.

***