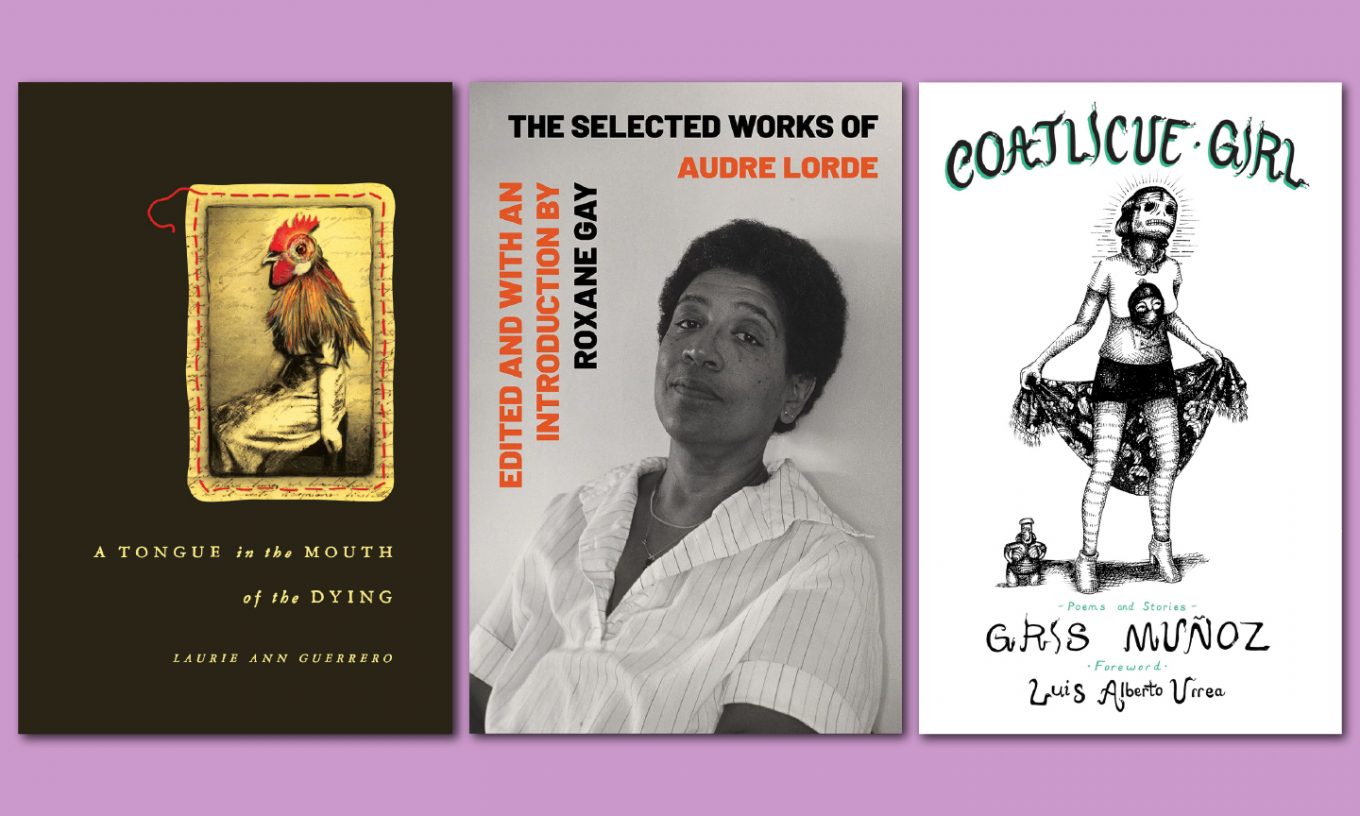

Poetry stands against a wall and this wall begs, pleads, to be demolished when a contemporary poet begins their first line. This wall is everything that has been done before: a sonnet, a turn, an elegy, Ezra Pound, Shakespeare, rhythm, meter, and so on. Poetry yields innovation, exploration; today’s poetry avoids imitation and strives for uniqueness in form and content. Poetry perpetuates itself in running the opposite direction of the status quo. Writers of color, in particular, build upon what they know of traditional poetic systems and create new forms, new ways of exploring the self. Laurie Ann Guerrero, Audre Lorde, and Gris Muñoz harness their respective poetic explorations as a means to disrupt and transcend the status quo. Utilizing personal experience and free verse, these three poets represent women writers of color working in opposition to the status quo: traditional white, Western poetics.

DECOLONIZATION IN THE POETRY OF LAURIE ANN GUERRERO

Laurie Ann Guerrero’s A Tongue in the Mouth of the Dying explores family, colonization, sexuality, motherhood, and Latinx linguistics. These self-explorations exist as a product of non-Western epistemology; Guerrero’s poetry garners knowledge through emotion and lived experience rather than Western theories of pure logic through scientific experimentation. Guerrero’s poetry lies in the outer scope of traditional criticism; this work is decolonial by nature.

Her poem, “On Eating Rattlesnake” describes her singular memory of the patriarchs of her family preparing a snake’s body to eat. The beginning of the prose poem establishes her young self as an unreliable narrator, yet the reader is still invited to partake in this specific memory: “maybe it was the one my father shot off the front porch, maybe it wasn’t…” (4). Guerrero revels in the maybe, but never undoubting the specifics of her memory that stayed. This seemingly unreliability creates a relatability between her and her reader because of the resilient language in the rest of the poem. She never claims to be omniscient, and this creates a sincere credibility. Her voice, then, lies within the protest of holding all the knowledge. She is exploring her memory on the page as the reader explores it.

The poem continues with “the men stood around the fire; the women sat inside. I snaked around the men hiding myself: slitherer” (4). Guerrero aligns her body with that of the rattlesnake that the men are preparing. Here, by using the verb “snake” to describe what her body is doing, she is playing with the linguistic relationship that arises, linking snake with self. This turns the human body animalistic, creating a visceral image for the reader to hold onto. Guerrero disturbs what the reader knows of the body to create a new image of the self.

Yet, disrupting the status quo of the body is not the only case of protest that Guerrero establishes. The poem’s content is a feminist text in opposition to the cultural domesticity of Latinas. While the women in her family do not participate in the eating of the rattlesnake, she “dug in, rough and curious: there was nothing more unashamed than a rattler. No apology in its tongue” (4). The rattlesnake becomes a representation of the counterpart of what is culturally stereotyped about Latinas. Guerrero wants to be like the rattlesnake, unafraid of its own tongue, unapologetically rough and raw. On the other hand, Latinas stay inside, they do not kill the rattlesnake, they do not eat the rattlesnake; they leave it to the men to act out machismo. In merging her body and her actions with that of the rattlesnake and the men that eat it, she is working against the status quo of her own cultural systems.

The poem ends with “I had to eat it. I had to know this” (4). This line speaks to decolonial epistemology, that is gaining knowledge through non-Western means. Guerrero learns through the act of eating an animal, in shedding her own skin, in behaving outside the “normal”, and in exploring emotions rather than logic. Guerrero embraces the realm where knowledge is found through other means rather than status quo reasoning. It is in the underbelly of tradition that she has found identity.

Guerrero embraces exploration through contradiction: human-snake body, specific language usage by an unreliable narration, and a protest against female domesticity. All this amounts to a poem that celebrates radical action and thought. You can be the rattlesnake and eat it too.

RADICALISM IN AUDRE LORDE’S “GENERATION” AND “GENERATION II”

In The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, Lorde employs free verse and confessional form poetry to explore American politics as it relates to the intersectionality in racism, sexism, and sexuality. Primarily, free verse poetry merges with a confessional voice which welcomes enjambment in lineation rather than attention to meter, or syllables, or rhythm; the poet is concerned with the flow of lineation with content rather than a starkly structured traditional form. In this way, a contemporary poet feels more in control, with more freedom to explore the world of the poem without the constraints of form. In Lorde’s poetics, racism, sexism, and sexuality stands for conformity (a verse poem) and dismantling these aspects of society stands for freedom (free verse poetry).

The feminist movement of the 60’s reclaimed the traditional sense of confession as a conduit for individualism from the Eurocentric male dominated autobiographical style. Confession is often associated with meekness as the confessional act suggests a submissive quality in revealing the self. However, the confession voice prides itself on the intention to showcase the poet’s experience and emotion with reverence. This same confessional voice is seen in Lorde’s poems, “Generation” and “Generation II” from The Selected Works of Audre Lorde. The speaker of the poem is directly related to the poet in the confessional style, so this urges the reader to read the poems as deeply personal away from the boundaries of a second- or third-person speaker. Thus, speaking in the “I” voice, Lorde directly presents herself as the speaker, the narrator, and the main character. The confessional voice creates a raw, authentic, and unedited reading of Lorde’s work.

Working alongside the confessional style, Lorde brings light to a shared voice, speaking as an individual a part of a larger community. Her poem, “Generation” employs the “we” to create a sense of community between the poet and audience: “We are more than kin who come to share/Not blood, but the bloodiness of failure” (189). Lorde radicalizes the sense of familiar community built from a shared, lived experience rather than a direct, blood relationship. Radicalizing the personal as political makes an individual experience like Lorde’s to act as representation of a community. This representation pushes against the status quo of the white-dominated spaces that marginalized communities exist in. Lorde’s poetics stand resilient against the -isms that oppress her and her community.

Lorde’s poetic exploration of short, fragmented lines in “Generation II” increases the speed of the poem. The poem sits on the page as 10 short lines, each line no more than 3 short words. The first line, for example, is “a Black girl” (222) which places that image at the forefront of the poem. “Going” is the second line of the poem and also stands alone and quickly, the reader arrives at “into the woman” (222). These short lines with no punctuation (save the period at the end of the poem) increases the rhythm of the piece. The increased rhythm creates a sort of urgency, an urged call to action to the future children of the Black community, in this case.

Speaking to the Black community, Lorde’s linguistically prioritizes her community and interrogates racism, and the generational trauma racism perpetuates. Both “Generation” and “Generation II”, speaks on generational trauma which utilizes decolonial theory. Even though Americans have no direct imperial nation breathing down our necks, minority communities still deal with the implications and trauma of past colonialism. In bringing the discussion of oppression to the surface, Lorde confirms the nuances in her own history and communal history in Blackness. Lorde transcends the cycles of generational trauma and brings a mirror to the face of the oppressor.

SUBVERSION IN GRIS MUÑOZ’S COATLICUE GIRL

Coatlicue Girl, with its bilingual storytelling, subverts Eurocentric poetic, linguistic standards. By blending language, code switching between Spanish and English, Muñoz challenges what language, especially bilingualism, creates on the page. In doing so, Muñoz’s poetry stands in protest against poetic tradition. In addition to linguistic subversion, her poetry’s content explores queerness, racial identity, Mexican mythology, and immigration. These topics are dealings of the marginalized, of the oppressed, and Muñoz’s poetry brings these to the surface.

The physical border between Mexico and the United States forms phycological, emotional, and cultural borders between people. Latinx writers, like Gris Muñoz, acknowledge the borders this creates in the bodies of Mexican Americans. We feel attached to Mexico, attached to the U.S. and yet, simultaneously a part of the space between borders. Her poem, “Fronteriza” is written in Spanish, the language of the colonizer and the language of the culture she grew up in. In this poem, Muñoz personifies la frontera, the border, and calls herself “una de [sus] hijas fronterizas,” one of the border’s daughters (13). The personification of the border and the subsequent familiar characteristic between it and the poet transcends liminal space and places the Borderlands as a character in the poem. Muñoz is one of the daughters of the Borderlands, making her a part of a collective, a community that exists outside the scope of traditional white culture.

The poem’s second stanza mentions the “othering” that occurs when Latinx identity splits: “de mi otro yo, mi otro lado yo me había olvidado” (13). Muñoz comments on the fragmented self of the Latinx body. There is the physical “other side”, el otro lado commonly referencing the other side of the border, and the phycological “other side” of the immigrant identity. By exploring this cultural phenomenon in poetry, Muñoz wishes to investigate with emotion—a theoretical approach in opposition to Western-centrism.

Additionally, Muñoz confronts her past idealism of Eurocentric beauty standards in her poem: “hasta tuve ganas de cambiar mi cara/mi nariz Maya” (13). When subjected to Western standards, marginalized communities find themselves internalizing racism. Through her poetry, Muñoz disrupts how this internalized racial aggression affected her identity. However, in writing in her native tongue and in taking back the power of the oppressor, Muñoz challenges the status quo and creates a new narrative for herself and her community. The poem continues with “linda tierra de mi abuela patria, no me des la espalda” which harkens back to the personification of the Borderlands and Muñoz desire to connect with her Mexican culture more than ever. The last line of the poem unifies the immigrant, marginalized, Latinx experience by saying “como princesa/entre tu pobreza/ y mis hermanas gastadas” (13). In merging a shared experience, Muñoz creates community among those that feel othered by Western culture. They are sisters tired from battle, sisters that need the solace of a welcoming homeland.

Gris Muñoz identifies as a frontera poet and storyteller. Her writing centers the Latinx experience of the Borderlands; the Border feels like an in-between place where identity merges and splits simultaneously. By showcasing the marginalized identity experience, Muñoz poetry places itself in that same liminal space where poetic traditional standards shift, change, metamorphosize into something new.

Poets Laurie Ann Guerrero, Audre Lorde, and Gris Muñoz exist in conversation with the same Eurocentric poetic tradition that they wish to subvert. The oppressed are experts in the language of the oppressor. Marginalized voices know the ways in which they are discredited by the voice of colonial thought. The works of these three writers of color use their linguistic and poetic exploration to counteract traditional standards, thus prioritizing their personal lived experiences to produce a community voice. The marginalized community voice dares the voice of the status quo; what occurs is the beautiful intricacy of the poet’s trueness, singing.

Consulted

Guerrero, Laurie Ann. “On Eating Rattlesnake” from New Work. I Have Eaten the Rattlesnake: New and Selected Poems. TCU Texas Poet Laureate Series, TCU Press, Fort Worth, Texas. 2020.

Lorde, Audre. “Generation” from The First Cities (1968). The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, edited by Roxane Gay. W. W. Norton & Company, 2020.

Lorde, Audre. “Generation II” from From a Land Where Other People Live (1973). The Selected Works of Audre Lorde, edited by Roxane Gay. W. W. Norton & Company, 2020. Muñoz, Gris. “Fronteriza.” Coatlicue Girl: A Bilingual Collection of Poems and Stories. FlowerSong Books, 2019.