Right after we moved to North Carolina my parents took me to a local square dance. I was barely old enough to remember, certainly too young to understand the calls and steps. But there were enough kids my age, we made up games in the corner of the barn and listened to the choreographed stampede. It was good, watching our parents swing. It reminded us that adults could play too.

Now that I know what it’s like to move to a new place where you don’t know anyone, I see why they went – to drink away some stress, to dance off some steam. And I guess they met some good folks, because we kept going every summer as I grew up.

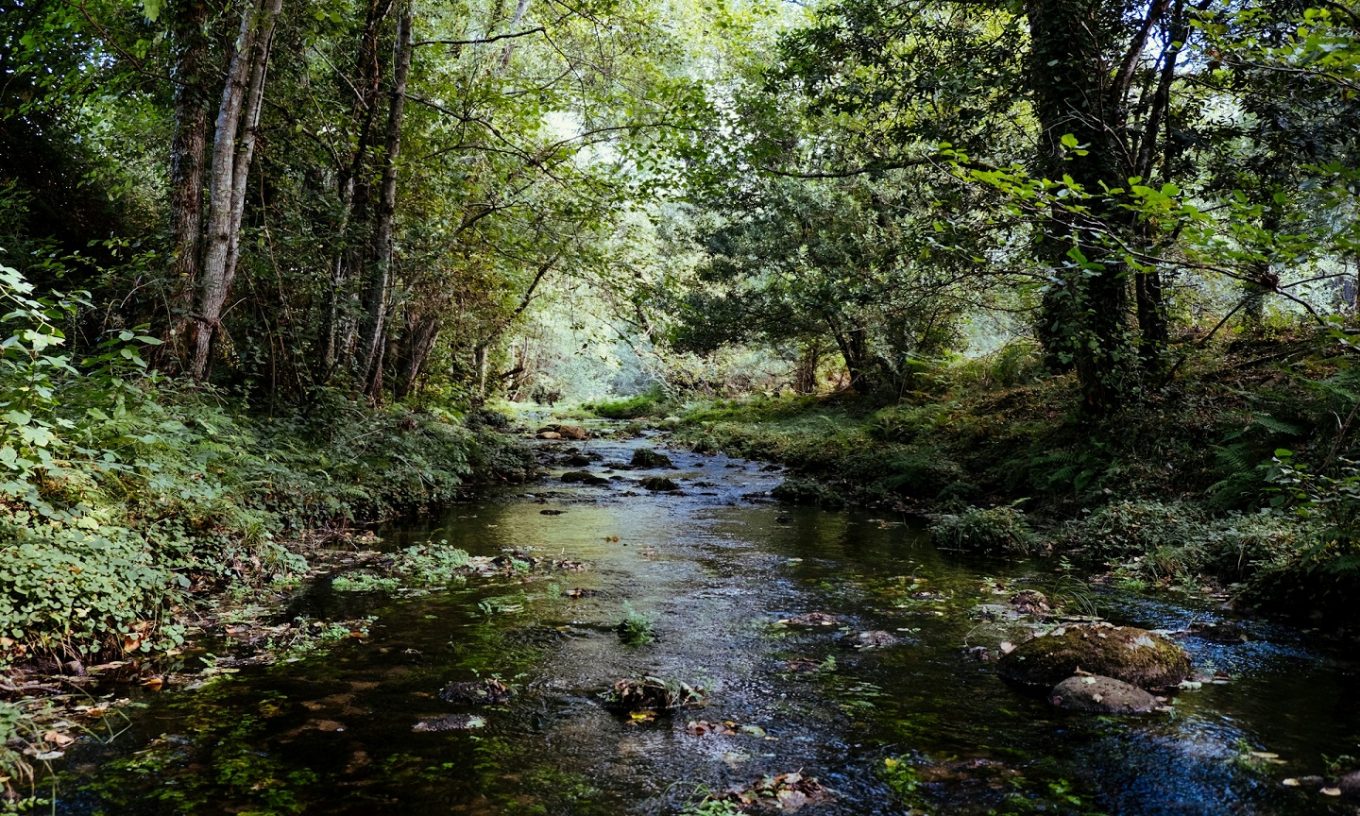

When I was seven, I was initiated into the group of older kids who knew their way down to the creek. The path was often muddy, you had to use roots for steps, and it led us out of the warm light that the barn breathed out. It was still close enough we could hear the music, or our parents calling if someone had to leave early.

We’d skip stones, and look for crawdads with flashlights. When the river was low, we could hop from rock to rock, and after the rain we could get in up to our waists. When the music stopped, we’d come up in a sopping line. “No way in hell you’re getting in the car like that,” our parents would say, and “hope you like walking home, bud.” But they never told us to not go back. Maybe because we didn’t bother them down there, or maybe because that’s how they wished they’d been raised.

I spent my eighth and ninth summer on Watson’s farm. The older guy who called the dance was called Watson, but I never figured out if that was a first name or a last. He had a dog called Fred, the friendliest Golden you’d ever meet. I swear, Fred was the only babysitter we ever had, ever needed.

When I was ten, a new kid showed up. This didn’t happen a lot, it was normally just the six of us who’d grown up around these dances. His parents must have moved here like mine had. But when I told him that he said it was different when you were thirteen and “had a life”. He seemed mad about it and didn’t dance, even though he was old enough. He said his name was Davie.

When I was twelve, I started dancing. Maybe it was so Malory would notice me, maybe I just wanted to see what my parents liked about it. The music was so loud, but not the type of commotion you wanted to run from. There was something comforting about the rhythm, something inviting about the tune. The old stand-up base kept time like a grandfather clock, the banjo and mandolin running laps around it like twin tricksters. Then the caller, at the head of it all.

“Alright, circle left now y’all.”

“Do Si Do!”

“Roll away to a half sashay.”

I got swept up in the assembly-line of percussion. Boots on floorboards, hands on knees. Thud, thud, clap. I know I made a ton of mistakes that first night, but everyone I bumped into just smiled and spun me back into place.

Later that summer, Davie joined in too. He had a way on the dancefloor. The old barn didn’t have lighting, but you’d swear a spotlight followed him around. But at the same time, he’d close his eyes, twirling like only the moon was watching. He was always barefoot, but his feet and cuffed pants were never dirty, and they carried him between dances so fluidly he had time for little flourishes. Malory and the other girls noticed him, even some of the parents looked impressed.

Every summer through my teenage years Davie appeared like the fireflies, a comforting light we all anticipated. He got attractive before I did, brown hair sun-streaked and intentionally messy like you saw in magazines.

Even after we started college, our summers wound back to a square dance at least once. The barn wasn’t as vaulted as I recalled, the creek-side slope not so treacherous. But it was also the same. The lightning bugs started to appear, as if coaxed out by the first few songs. I wasn’t yet twenty-one, but my parents let me take a beer from the cooler.

Dusk cast the whole scene in the shadows of memory. I was a kid again, or I danced with him, his little hands in mine. Eras bled together in this place, young and old dancing. That music had been bringing people together longer than I’d been alive. The trees, the tradition, would outlive me.

I got as hot and sticky as the August air and left the barn behind.

I found myself on a rock, the water was high, black and glassy like oil.

Davie walked up and sat without asking.

“Still coming to these things too?” I asked.

He laughed, “Actually, been dancing a lot in Boone, the campus throws some, but if you know the right people you can find something every weekend.”

“Nice… I don’t think I’ve danced since last summer,” I admitted.

“No way, really? I couldn’t… I’m like a shark. I would die if I stopped dancing.”

We listened to the diluted blue-grass for a while, hardly louder than the river-frogs.

“I’m surprised you’re not the same way,” he said. “I never would have gotten out there if you hadn’t first.”

“Wait, really? I just did it so Malory might think I was old enough to kiss.”

“There’s always that,” he smiled. “Add it to the list of life-changing innovations done to get a girl’s attention… or a guy’s.”

He put his arm around my shoulder. I wasn’t sure if we’d touched before, except for holding hands when the caller told us to.

“Yeah, I don’t know. You were younger than me, and quieter, kind of nerdy.” He chuckled. “I couldn’t let everyone see you do something I was scared to, so I powered through my anxiety and realized I loved it.”

“That’s funny. I thought you’d just been born to dance.”

“I never would have known without you.”

Photo by Karim Sakhibgareev on Unsplash