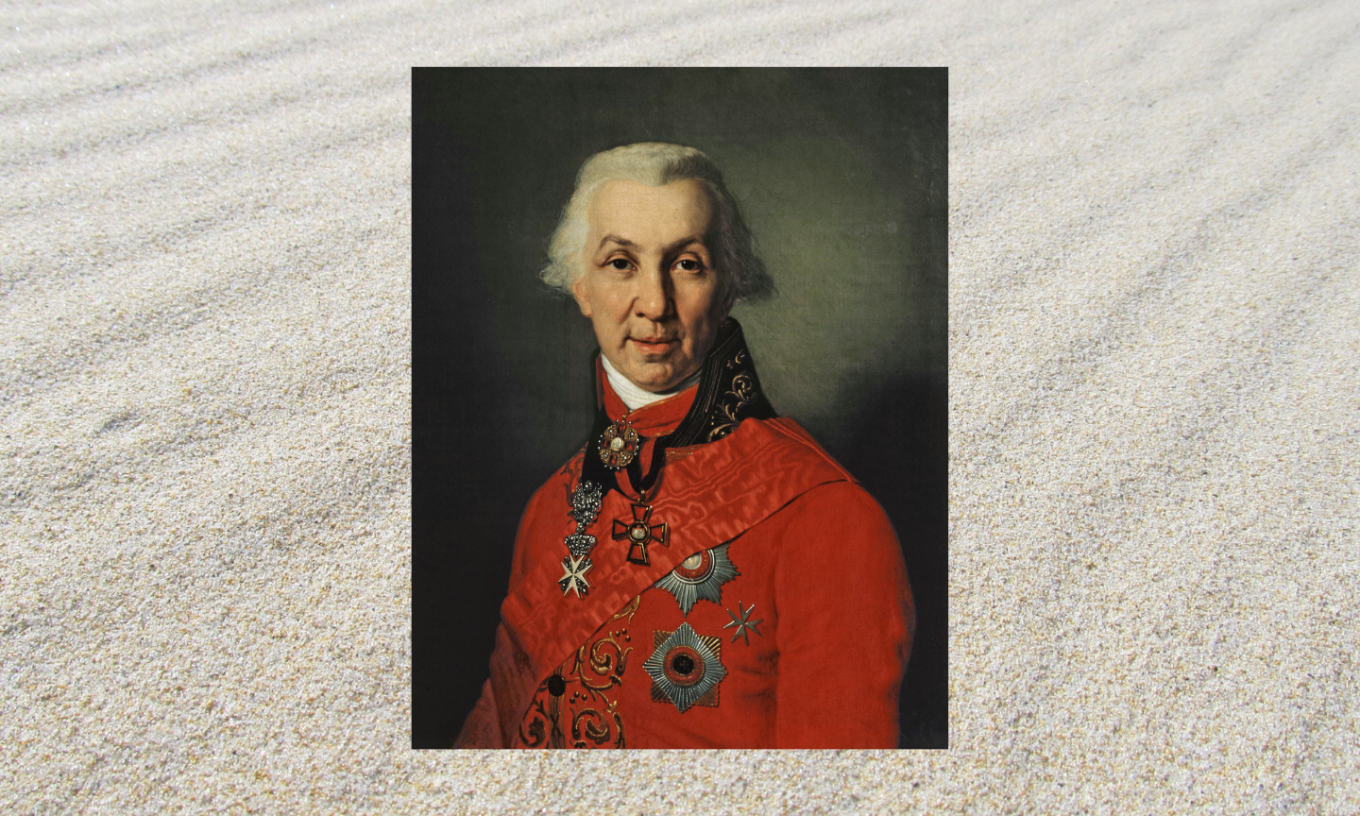

A NOTE ON THE POET:

Gavrila Derzhavin (1743-1816) wanted to be remembered more for his role as a statesman than for his poetry, which, in accordance with the values of his age, he compared to “delicious lemonade.” Nevertheless, it is his poetry that has made him “immortal.” Born into a family of the minor gentry in Kazan’ and tracing his ancestry back to the Tartar nobility of that city, he went on to serve in the imperial army during the Pugachev rebellion and to become a confidant of Catherine the Great; his interest today, however, is to be found in his sense of integrity and independence in his relationship to those in power. In this respect, while “speaking the truth to Czars with a smile,” in his work he urged humanity above all and dedicated his odes to heroes precisely as they fell from royal favor, courting the same fate himself out of a deeper sense of justice. He was among the first to introduce subjective, aesthetic experiences into the Russian lyric, at a time when poetry was largely devoted to praising the majesty of the Czar. Ranging from satirical realism to sublime disorder, his poetry contains a profound call on individual virtue in inconstant times as well as a sense of how the maw of eternity swallows all human things. It was Derzhavin who personally passed the baton to Pushkin, who in turn considered Derzhavin a poet of universal significance. Now he is remembered wherever the Russian tongue is spoken, and he has been an important touchstone for such modern poets as Khodasevich, Mandelstam, and Brodsky. The poems translated here represent imitations of drinking songs, anacreontic lyrics and their self-parody, satire on the corrupt Russian nobility, laments for lost virtues in a degraded age, adaptations of the psalms and Horatian odes, and profound reflections on time and death, written, in part, in response to the Night Thoughts of Young. The translations are not made to reproduce all formal and semantic features of the original, although in an important sense they do remain faithful. Instead, they derive inspiration from the English baroque and 18th century tradition (Milton; Gray, Collins, Young) to create a language that translates Derzhavin’s sensibility, standing at the threshold between Classicism and Romanticism, into English.

On the Death of Prince Meshcherskii

Time’s final Word, your awful chime,

The groan, monotonous, heavy groan,

Your metal voice unnerves me,

Calls me nearer to the grave. Just when

I’ve got this world in sight, it goes.

Death gnashes teeth,

Its lightning flashing scythe

Cuts down my days by stalks and rows.

No one eludes its clawing arms,

No thing or creature achieves escape:

The monarch, prisoner, one food for worms;

The hateful elements eat even tombs,

And yawning time gobbles glory up.

As water into the sea

So rushes to eternity

The kingdoms sateless death chews up.

We skate the rim of an abyss

And fall head-in at last. We take

As one, life, death, both stacked in us.

We’re born to die; the pitiless stroke

Of death attains us all. The stars

Are crushed and suns spin out

And brought to grief by it,

Which threatens all, worlds and creatures.

Only mortals think they will not die,

Their aim and hope to be immortal.

Yet on comes death, thieving sly

With sudden larceny to pull

The life. Where fear is lulled, abates,

There falls death upon

Us all the faster than

Flies even lightning on proud heights.

O prince, son of luxury, ease, retreat,

Where gone to hide? What deadman’s land,

Subtracted from the living shores? Here’s dust.

Your spirit’s where? Can we understand

And point to there, knowing where,

Having only, abandoned, -no!-

Our challenging cries? O woe

To us born into this sphere.

Where joy and love, diversions once

Played together with health in flower,

There the blood sets, no matter whose,

The spirit’s stunned with grief. Where

Our table’s laid the body’s walls

Are placed. Where festive hoots,

There howl and wail laments.

Death’s on watch for all and pales.

Death looks on everyone, both czars,

By whom as sovereign the cramped world

Is led, and on pompous sirs,

Rich and idols of silver, gold,

And looks on beauties, delight, charm,

And looks on heights of mind,

On strength and daring and

The blade of death grows sharp and warm.

Death, trembling, fear built

In nature; we’re poverty and pride at once:

Today a god, tomorrow dust.

Flattering hope today wins,

Tomorrow, man, where’re you then?

Grains just begin to pass

To Chaos in its glass abyss,

And your life entire, a dream, is gone.

Like a dream or pleasing sleep,

My youth too has already passed,

Nor does beauty work as deep,

Nor does joy beat in me as fast,

Nor mind play as frivolous a game,

Nor blessed as full by fortune

And yet still, ambition:

I hear the noise of glory, fame.

But even courage will go this path

In company of the impetus to fame.

The hoarded cajolery of wealth,

Desire that buckles the heart, the same

In turn, they pass – away, every

happiness, from me, here you

Are known to change, untrue,

For I stand at the doors of eternity.

This day, the next, or next, we die,

Perfil’tsev, we the same as all.

Why torture ourselves with grief, why

For a friend who didn’t live forever mortal?

This life, heaven’s ephemeral gift,

Arrange it to peace

And, my friend, bless

With your pure soul every blow of fate.

***

НА СМЕРТЬ КНЯЗЯ МЕЩЕРСКОГО

Глагол времён! металла звон!

Твой страшный глас меня смущает;

Зовёт меня, зовёт твой стон,

Зовёт — и к гробу приближает.

Едва увидел я сей свет,

Уже зубами смерть скрежещет,

Как молнией косою блещет,

И дни мои, как злак, сечет.

Ничто от роковых когтей,

Никая тварь не убегает;

Монарх и узник — снедь червей,

Гробницы злость стихий снедает;

Зияет время славу стерть:

Как в море льются быстры воды,

Так в вечность льются дни и годы;

Глотает царства алчна смерть.

Скользим мы бездны на краю,

В которую стремглав свалимся;

Приемлем с жизнью смерть свою,

На то, чтоб умереть, родимся.

Без жалости всё смерть разит:

И звезды ею сокрушатся,

И солнцы ею потуша́тся,

И всем мирам она грозит.

Не мнит лишь смертный умирать

И быть себя он вечным чает;

Приходит смерть к нему, как тать,

И жизнь внезапу похищает.

Увы! где меньше страха нам,

Там может смерть постичь скорее;

Её и громы не быстрее

Слетают к гордым вышинам.

Сын роскоши, прохлад и нег,

Куда, Мещерской! ты сокрылся?

Оставил ты сей жизни брег,

К брегам ты мёртвых удалился;

Здесь персть твоя, а духа нет.

Где ж он? — Он там. — Где там? — Не знаем

Мы только плачем и взываем:

«О, горе нам, рождённым в свет!»

Утехи, радость и любовь

Где купно с здравием блистали,

У всех там цепенеет кровь

И дух мятется от печали.

Где стол был яств, там гроб стоит;

Где пиршеств раздавались лики,

Надгробные там воют клики,

И бледна смерть на всех глядит.

Глядит на всех — и на царей,

Кому в державу тесны миры;

Глядит на пышных богачей,

Что в злате и сребре кумиры;

Глядит на прелесть и красы,

Глядит на разум возвышенный,

Глядит на силы дерзновенны

И точит лезвие косы.

Смерть, трепет естества и страх!

Мы — гордость с бедностью совместна;

Сегодня бог, а завтра прах;

Сегодня льстит надежда лестна,

А завтра: где ты, человек?

Едва часы протечь успели,

Хаоса в бездну улетели,

И весь, как сон, прошёл твой век.

Как сон, как сладкая мечта,

Исчезла и моя уж младость;

Не сильно нежит красота,

Не столько восхищает радость,

Не столько легкомыслен ум,

Не столько я благополучен;

Желанием честе́й размучен,

Зовёт, я слышу, славы шум.

Но так и мужество пройдёт

И вместе к славе с ним стремленье;

Богатств стяжание минёт,

И в сердце всех страстей волненье

Прейдёт, прейдёт в чреду свою.

Подите счастьи прочь возможны,

Вы все премены здесь и ложны:

Я в две́рях вечности стою.

Сей день, иль завтра умереть,

Перфильев! должно нам конечно, —

Почто ж терзаться и скорбеть,

Что смертный друг твой жил не вечно?

Жизнь есть небес мгновенный дар;

Устрой её себе к покою

И с чистою твоей душою

Благословляй судеб удар.

***

Notes:

An extended reflection on time and death, this is one of Derzhavin’s most celebrated poems. It was written on the occasion of the death of the poet’s friend, Prince Meshcherskii. Although the work presents itself as an ode, it violates the conventions of that genre. Odes were typically devoted to a majestic figure or glorious deed, but Derzhavin says almost nothing about his subject’s life or accomplishments. Instead, in the death of his friend, a kind of “everyman,” the poet contemplates the power of mortality, a cosmic force which reduces people, kingdoms, worlds, and stars to nothingness. For English readers, the poem recalls Edward Young’s “Night Thoughts,” which Derzhavin read in German translation.

CONFESSION

Inflate myself to stature and importance,

Pull the face of grave philosophy?

I preferred a heart

Frank and open, thought only to please

by it. The human heart,

The human mind, my simple muse.

If rapture sparkled, if fire flew

from my strings, the light was not

my own but God’s; of god

I sang outside myself. If my lyre’s

Song and sound

Were dedicate to Tsars,

In virtues seemed they equal to

The gods. If I wove wreathes

For generals in their victory,

My aim: to pour their spirit

Into their progeny,

Remind the children of their merit.

If in hearing of mighty lords

I dared to speak tactless truth,

My aim: to be a friend

To Tsar, to fatherland, to them

With heart unbiased. And

If ever I was seduced by the foam

Of the world, I sang, I confess,

As beauty’s captive, woman: in short,

If love’s fire was burning,

In me, I fell, and rose

In my day. O men of learning,

If you know yourself as one of those

Who’s ceased to be a human being,

Then cast your stone at my grave.

***

ПРИЗНАНИЕ

Не умел я притворяться,

На святого походить,

Важным саном надуваться

И философа брать вид;

Я любил чистосердечье,

Думал нравиться лишь им,

Ум и сердце человечье

Были гением моим.

Если я блистал восторгом,

С струн моих огонь летел,

Не собой блистал я — Богом;

Вне себя я Бога пел.

Если звуки посвящались

Лиры моея царям, —

Добродетельми казались

Мне они равны богам.

Если за победы громки

Я венцы сплетал вождям, —

Думал перелить в потомки

Души их и их детям.

Если где вельможам властным

Смел я правду брякнуть в слух, —

Мнил быть сердцем беспристрастным

Им, царю, отчизне друг.

Если ж я и суетою

Сам был света обольщён, —

Признаюся, красотою

Быв пленённым, пел и жён.

Словом: жёг любви коль пламень,

Падал я, вставал в мой век.

Брось, мудрец! на гроб мой камень,

Если ты не человек.

Notes:

In his own prose “Explanation,” Derzhavin described this poem in a single sentence: “The explanation of my works.” The poet says that he never had the ambition of being a scholar or a saint, but rather to be human. He explains this by recalling the features and subjects of his poetry, its fiery energy, his praise of Czars, and celebration of heroic victories, only to explain with humility that the energy came from God, that at the time he thought Czars were virtuous, and that through his poems he hoped to perpetuate illustrious examples. He goes on to recall his propensity to speak “tactless truth” to the powerful and to admit that, as a man of human passions, he sang the beauty of woman. He concludes by saying that if posterity wants to remain human as well, it should not condemn him.

ROMANY DANCE

Roma girl, take up your guitar,

Strike across its strings and shout;

Voluptuous, with beading fever,

Ravish us all with your dance.

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

Fury, luxuriant, drumming nerve,

languish, melting feel of love,

the ancient magic skill revive,

All Bacchant spells at once revive,

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

Like night – flash your twilight cheek;

Like a whirlwind – spin the dust with your cape;

Like a bird – fly closer wings and strike

your palms and piercing cry.

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

At night, under forest pines

and the full moon’s pale gleam,

stomp on the coffin’s pines,

Rouse dead silence from its sleep,

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

And your evhoe, fearful cry,

Trailing distance lost in howls

Of dogs, rolling moan, frightful clap,

Pour love into the sensualist.

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

No, enough, stop, arch-charmer,

frighten no more the modest muses,

Graceful, majestic now, take measure,

End with steps a girl of Russia uses.

Glance of smoldering sun,

Burn souls, cast fire into hearts.

***

ЦЫГАНСКАЯ ПЛЯСКА

Возьми, египтянка, гитару,

Ударь по струнам, восклицай;

Исполнясь сладострастна жару,

Твоей всех пляской восхищай.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

От смуглого лица.

Неистово, роскошно чувство,

Нерв трепет, мление любви,

Волшебное зараз искусство

Вакханок древних оживи.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

От смуглого лица.

Как ночь — с ланит сверкай зарями,

Как вихорь — прах плащом сметай,

Как птица — подлетай крылами,

И в длани с визгом ударяй.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

От смуглого лица.

Под лесом нощию сосновым,

При блеске бледныя луны,

Топоча по доскам гробовым,

Буди сон мертвой тишины.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

От смуглого лица.

Да вопль твой, эвоа! ужасный,

Вдали мешаясь с воем псов,

Лист повсюду гулы страшны,

А сластолюбию — любовь.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

От смуглого лица.

Нет, стой, прелестница! довольно,

Муз скромных больше не страши;

Но плавно, важно, благородно,

Как русска дева, пропляши.

Жги души, огнь бросай в сердца

И в нежного певца.

***

Notes:

This is part of Derzhavin’s poetic dialogue with his friend I.I. Dmitriev. Derzhavin had previously published an anonymous poem addressed to Dmitriev, in which he assumed the latter was spending the summer at his idyllic country home. Recognizing Derzhavin’s distinct voice in the piece, Dmitriev published a poem of his own to say that he was spending the summer in Moscow because he found no inspiration in the countryside. He complains of “ravens drowning out the nightingales” and frightening songs and shouts of Romani chasing the birds and people away. He concluded by saying that only Derzhavin could make poetry out of that. Derzhavin accepted the challenge by writing this poem, which compares the music and dance of a Romani girl to the Dionysian Bacchants of ancient Greece.

Translators’ Bio:

Peter Orte is Visiting Assistant Professor of Russian at Williams College in Massachusetts.

John Hamel has published many poems and translations over the years at magazines such as Arion, Forum Italicum, Notre Dame Review and American Journal of Poetry.