From the Editor’s Desk

The periphery is a place that carries the resonances of multiple existences within itself. In that sense, the periphery is also a cusp: holding back – withholding – waiting to birth. The place where stories gather at the edge; where they emerge and disperse with the wind, water, sun, the soil. The place that lends context; the place where walls are broken down and new pathways emerge. The zone that is both surrounding darkness and where morning meets night; the sky meets land, the sea meets the sky, where land connects with land, speaking through the swishing grass, the rolling pebbles, the often-washed sand, the moon-cooled, sun-warmed bracken, bramble, bedrock.

Often, we live at this periphery, around the edges – of language, memory, consciousness, hope, fear, love, ambition, of life itself. In that moment/ place when things might change, shift, take flight, or hold still. A place where we may be unseen, unheard, yearning perhaps for the very negation of this state of being. Center and periphery speak to each other, they speak to themselves in a polyphony – raw, immediate, urgent, throbbing.

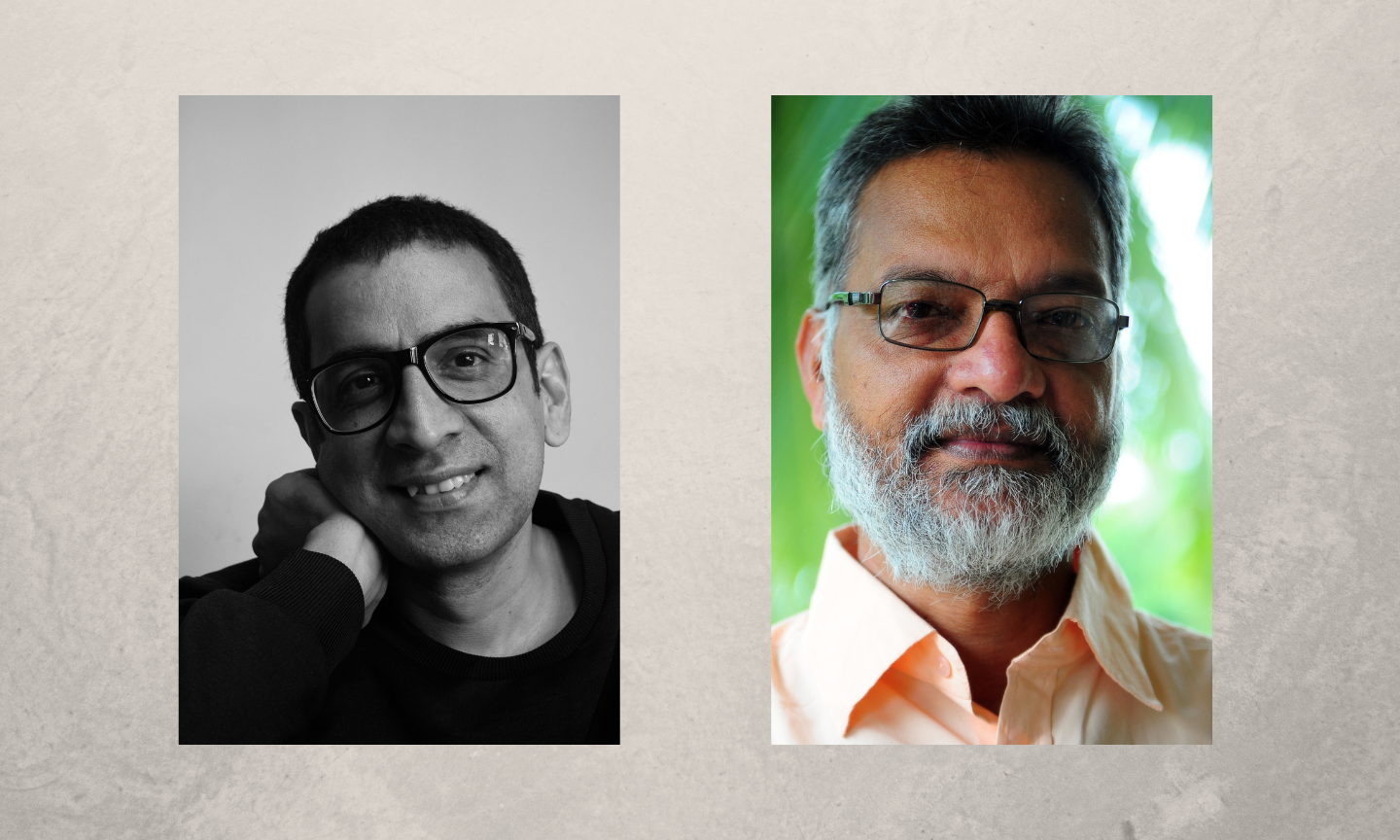

The stories in this fiction special speak from and to the peripheries and edges in various ways. The issue has been loosely compiled in five sections: Peripheries – Of Being and Living; Promises Made and Promises Broken – the NATURE of things; Queering Language; and Writing from the Peripheries of Language (guest edited by Kamalakar Bhat). Apart from the stories, we bring to you a conversation with Dr A J Thomas and Ashutosh Potdar, editors of The Greatest Malayalam Stories Ever Told and The Greatest Marathi Stories Ever Told, titled Anthologies – The Editorial Perspective.

There’s a rawness to some of these narratives that is not an oversight. It is the way the stories are meant to be. I hope the rawness speaks to you, that you hear:

- The haunting echoes of abandoned courtyards in conversation with a pair of ghosts who do not know “what they must do with their extinction”. The agony of a ‘Jokhini’ in love with a princess, seemingly helpless but determined to chart her own destiny beyond death. The trauma of parents, teetering on the edge of memories and dreams, the past and the future. The frustration of a man having to navigate daily living when all he wishes for is to shed excess baggage, to exist, away from this throbbing hub. The speculative horror of a future where water is both an absence and a threat. The dilemmas and confusion of a student as he hovers between self-acceptance and self-abasement, yearning for love and acknowledgement. The lover who murders for the man he loves but harbors no regrets, accepting instead, the truth and his own incarcerated non-existence.

- The Hidatsa prayer songs in the backdrop of greed, drugs, and violence over oil in the Indian reservations. The tension and confusion of an Afghan woman hoping for asylum but also shying away from losing her land, her identity. The Nepali immigrant on a trip to Nepal caught between feeling patriotic and aspirational, craving citizenship in the Western world as well as acknowledgement of his belonging to the country of his birth. The woman who, seeking escape and inspiration, ends up abused by an unknown assailant, yet is replenished emotionally by the muddy earth that holds her up, cups her body, fuels her imagination. The woman who marries a tree rather than hurt it to gain marital bliss.

- The bold storytelling of Dr Raj Rao, one of the foremost and most powerful voices in queer literature, in the excerpt from his book Mahmud and Ayaz. The seven stories from Konkani, Deccani Musalmani, Bhojpuri, Rajbangshi, and three Dalit stories from English, Hindi and Kannada – that “not only speak from the periphery but also speak of it and to it.”

Multifarious things speak to us: buildings and courtyards; our bodies; our social conditioning; our environment; caste-class-language-gender. The idea of writing our stories, from the edges, from the peripheries, in the shadows and into the shadows. Stories that contain multiple worlds and their shadows within; they leave behind traces that connect one to another.

The langur perched on the edge of a depleted water body where its reflection is an absence, comes along with the dry grass in the background, the shadows collected in the bramble, that lend context to the image. Each speaks to the other. If we don’t resist, each of these will lead us to other stories winding through the cracks in the soil, along the dried roots and trunks waiting to rejuvenate. Each story with the potential to branch off into multiple others.

Let us wander, then, into the peripheries of this landscape still hidden from us. Let’s listen. Come along.

Sucharita Dutta-Asane

Fiction Editor, The Bangalore Review

December, 2024