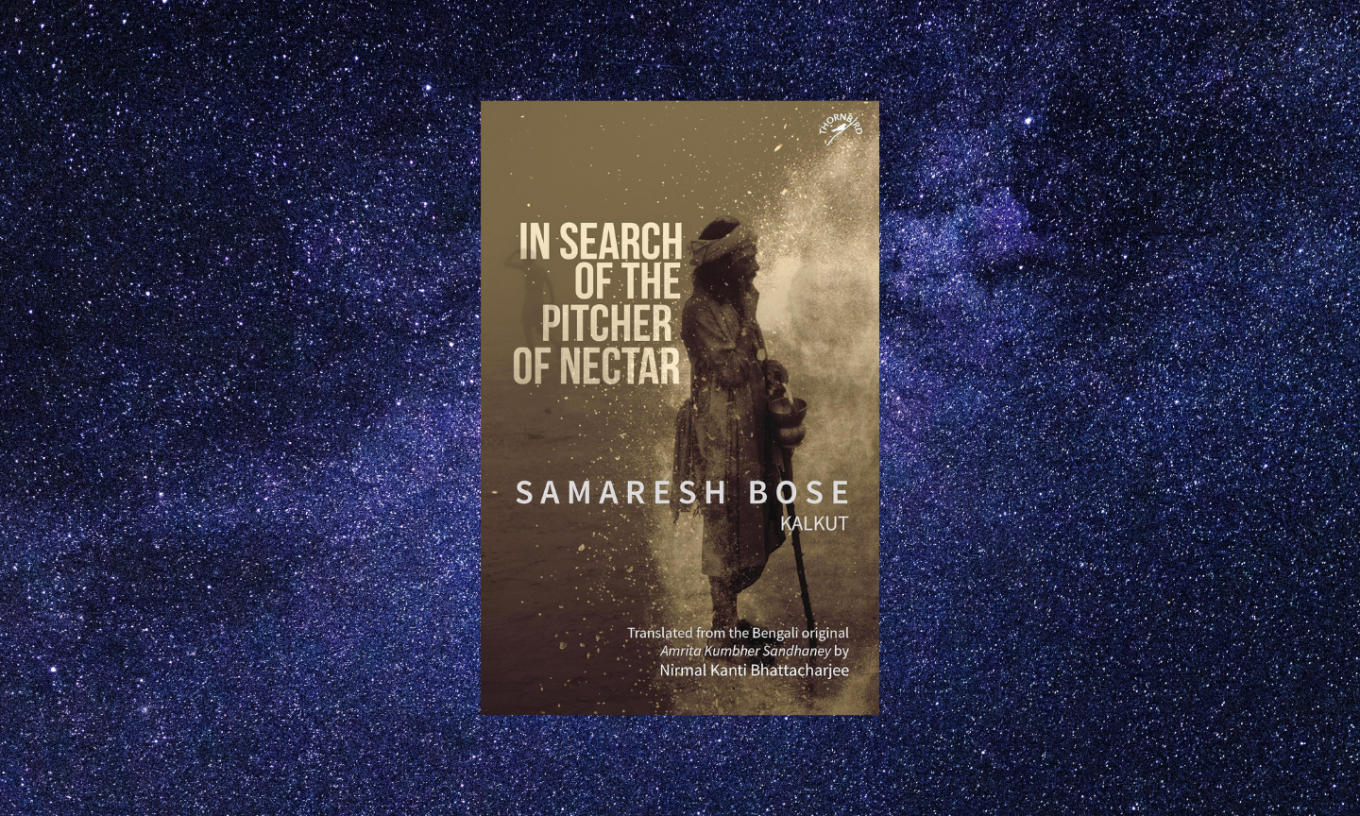

Title: In Search of the Pitcher of Nectar

Author: Samaresh Bose (Kalkut)

Translator: Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee

Publisher: Niyogi Books

Year: 2022

Reading Samaresh Bose’s (writing as Kalkut) In Search of the Pitcher of Nectar, is like looking through a prism. Nirmal Kanti Bhattacharjee’s deft translation of the 1954 travelogue Amrito Kumbher Shondhane, is evocative and holds its own in bringing what could possibly seem to be a dated narrative of a time we have left far behind. This is where the prismatic effect comes into play. It enhances our consciousness of the single story that the book presents – that of travelling to the Kumbh at Prayag. And then it splits this single context and experience into their myriad constituents.

Travel is synonymous with search. It doesn’t beg a reason. The desire to travel inherently holds the desire to seek – whether simple relaxation, pleasure, the destination, the journey… All travel, therefore, is a process of exploration. Travelogues, when written effectively, reflect this process. And in ‘the process’ thus presented, the narrator who begins the journey is rarely the same by the time the journey ends, especially when the journey is a pilgrimage. In that sense, a pilgrim’s journey is a deeply spiritual movement, between a point of departure that may be static and a point of return that is dynamic, for the journey doesn’t end, except physically.

“Travel makes one modest,” said Flaubert. “You see what a tiny place you occupy in the world.” Add to that the fact of travelling to observe a religious gathering at a historical place, the possibilities begin to seem endless, the potential for discovery, fathomless.

In In Search of the Pitcher of Nectar, the individual, the deeply egoistical, the self, seems to be but a blink in the cosmos when pitted against the vast multitudinous humanity and its various complexities. What could be a better trope to convey this than an Indian train compartment?

The narrative is bookended by two train journeys, the one that takes the seekers to Prayag, and the one that brings them back, each having gone through their own personal and collective journeys. And so, as the author steps into the train that will take him to Prayag, to the first Kumbh mela in independent India, we are pitched into this varied universe from the word go.

The train compartment serves as a microcosm of the universe that the Kumbh represents. It brings disparate people together, all journeying towards the Kumbh fairgrounds. Each individual and each step in this journey fraught with challenges and discomforts, encompasses worlds within worlds – of the personal, the collective—the risky adventure of getting off the train, the doubts and fears in the journey towards the Kumbh mela grounds, the ordeal of finding a place to stay among the multitude of tents and camps along the river banks, the exercise in religiosity and spiritual pursuits, whether deep or superficial.

As the pilgrims wind their dusty way towards their destination, we get glimpses of history that the narrator deftly recreates for us, deftly but not extensively. The information thus handed to us is just enough to tempt us into further exploration, but on our own. The writer’s immersive experience during the journey, his vivid imagination, along with his recollection of historical events weaves a momentous sense of time, steeping it in the historical and spiritual continuity of the place. At a time when history is learnt from dubious WhatsApp forwards, it is a pleasure to read passages such as this:

We, the Kumbh-goers, were using today a path steeped in history. We could find the dust of Gautam Buddha’s lotus feet on this road. If we put our ears on this road, we could hear the victorious march of the Mauryan army. We could see the deeply enchanted Greek Ambassador Megathenes or the Chinese traveller Fa-Hien. We could hear the rattling sound of the wheels of the chariots of Samudragupta and Harshvardhan. We could detect the footprints of Hieun Tsang and Shankaracharya.

But that history is of Prayag, not of Allahabad. … The great Mughal emperor came to Prayag and re-christened it as Illahabas… Shahjahan renamed the city Illahabad.

After that also, Illahabad suffered the aggression of the ruthless Bunela rebels and the dauntless Maratha cavalry. The soil of Illahabad was soaked with the blood of fallen soldiers. At times, the canons of the Mughals occupied it, at other times, the swords of the Marathas.

Then there was total darkness. The debt-ridden Nawab of Oudh sold her to the East India Company.

Today we are marching on her. We are not historical travellers, but history is being created in our mind.

(pg 53-54)

As the writer meets different people – baul singers, avadhuts, naga sadhus, widows, wastrels, devotees, seekers of all kinds – we see the continuous flux of movement happening around him, the sifting and the sorting in his mind reminiscent too easily of the proverbial churning itself. In every interaction, we get a sense of the individual within the universal and vice versa. This thread wraps itself around the length of the narrative, drawing attention, sometimes too overtly, at others at a slant, to the realization that we are but specks in a limitless cosmos. And yet, almost no one who journeys in search of the nectar of God’s benediction is able to discard the soiled robes of prejudice and bias, of racist and class-conscious behavior, of chauvinism and superciliousness. None of that can be washed away by the water that draws thousands of people for the expiation of their sins and sorrows. And yet, in the end, it is the human being that triumphs over all odds, faith intact, ready to embrace whatever befalls.

The narrator’s “urban mind” of a “trained reformist” is thus overwhelmed, again and again, by the simple and simplistic emotions of many of the pilgrims who crowd the river banks in search of the nectar that the Kumbh promises, the salvation that a dip in the Sangam will bring about. Skepticism falls by the wayside, crumbling into the sand, to be replaced repeatedly by faith in humanity, in its capacity for goodness, for the simple joy in having faith.

“I remembered Rabindranath Tagore’s message on his last birth anniversary,” he writes. “He said, ‘It is a sin to lose faith in humanity.’” (pg. 136).

The spirituality he slowly begins to comprehend is full of the mysticism and the mystery one associates with Hinduism in its diverse forms and practices, the shadows more eloquent than what is evident in the light of ‘knowing’.

The writing is often gripping in its description of moments and of people, the writer’s engagement with the experiential moment as intense as the moment of writing through recollection. The translation, so many decades after the book was written in Bengali, reconnects us with a past of which we have no recollection. It shows us a nascent nation, still not familiar with the challenges of the future, of the fundamental practice of religion that would one day disrupt national life and discourse. Seen in this light, the naivete with which the author comments on certain phenomena, is a welcome breather that reminds us of a less vitiated atmosphere but one that nevertheless holds in its cusp the possibility of hatred spilling over, albeit six decades into the future.

The constant recall of Bengal and scenes from there begin to jar upon the modern reader brought up in a more globalized world. The constant comparisons appear as both spiritual limitation as well as a linguistic, cultural resistance. However, on pilgrimage thousands of miles away from home, at a time when communication was not advanced, this would have had an emotional recall or connect difficult to ignore then and to imagine now, when life is an endless string of social media pictures and posts. Reading an old text in the context of contemporary flux is an interesting experiment for the reader, especially at a time when old texts are sought to be revised to meet modern tastes. If all texts are to be thus rendered, or if all texts are to be judged according to modern paradigms, what happens to the archival potential of past literature?

Kalkut’s engagement with the Kumbh at Sangam embodies the spirit of search, of seeking, whether as an observer or as a seeker of a path, of a drop of nectar, or of a guru. Each of these takes on various forms, degrees of involvement and of intensity, of acceptance and rejection. But each interaction, each instance of discovery, of learning, serves as the guru, the thing or person that shows the way.

I stopped near the water. A hundred faces came flocking around before me. They all got submerged in the procession of the lakhs of faces in the Kumbh-mela. I had met so many gurus here – on the road, in the stretch of sand, in cottages, slums, buildings, at home and the world. I bowed before these numerous gurus.

(pg. 268)

The travelogue follows a simple narrative arc. It begins with the start of a journey, the sense of not knowing what one is going to experience; it peaks with a heightened sense of the religious environment in which the narrator finds himself, the coming into being and quickening of all the senses, and the dawning of a semblance of spiritual understanding; and then the slow-burn winding down, the quietening of the senses, the spirit of return but with the mind awake to all that has been and all that might be.

This wakening and mindfulness hold the narrative together, for writing a travelogue is writing through remembrance rather than in the throes of the experiential moment. This learning twice over, once at the moment and then again in retrospect, in its dwelled-upon-in-solitude way, weaves itself into the preface of the book:

I have not seen anything more strange than a human being. I have seen the infinite beauty among this strange creation of God, though I used to think that I would find Him somewhere else beyond humanity.

And so, the traveler who returns is not the one who had set forth…