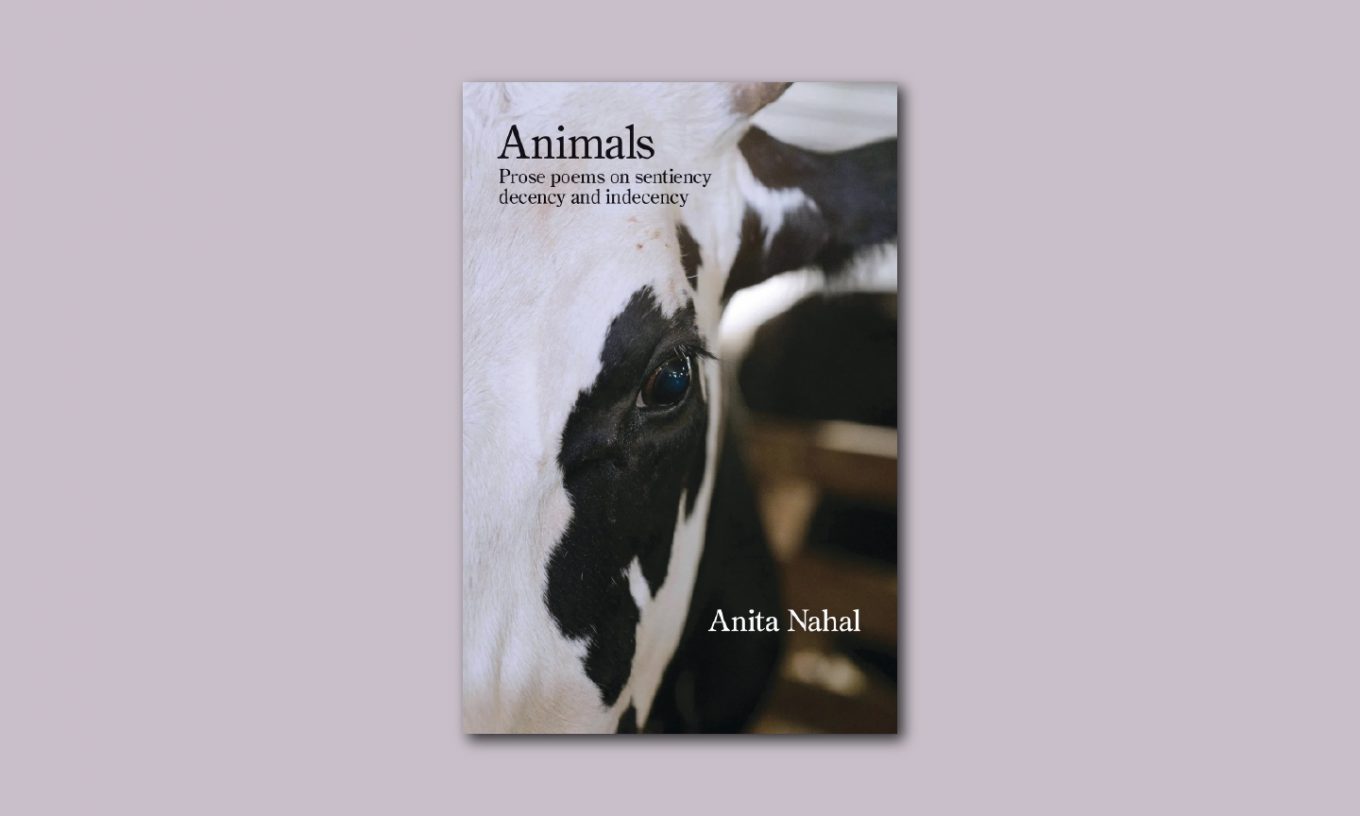

Animals: Prose Poems on sentiency, decency and indecency by Anita Nahal, Kelsay Books, Utah, USA, 2025.

Animals is not a book for the lily-livered. It is a gut-wrenching narrative that has emerged after extensive research done by the author. Reading the book alludes to an experience in the raw of what it means to be an animal in this predatory world. The author, Dr. Anita Nahal uses the term ‘animals’ to include all sentient beings such as birds, aquatic lives living in oceans and rivers and insects. It is a thoughtfully undertaken response to the way humans behave with these animals, our co-inhabitants on planet Earth. This volume ‘is a nod of veneration to living beings that exist in the circle of life,’ says Nahal in her Introduction.

Dr. Gerrit Diellessen, Professor of sociology at Utrecht university, the Netherlands, remarks succinctly that Nahal’s book ‘transforms the derogative “animals” into an honorific’, adding that it ‘truly heralds a special dawn of humanistic engagement and self-reflection.’ And John Burroughs, US National Beat Poet Laureate (2022-2021) remarks on how the book makes us ‘contemplate the inner lives and feelings of other species.’

In her Introduction, Nahal, a Fulbright scholar who teaches at a university in Washington D.C., shares Mahatma Gandhi’s vision: ‘There is little that separates humans from other sentient beings. We all feel joy; we all crave to be alive and to live freely and we all share this planet together.’ She seeks to address ‘major issues of global animal rights’ that she lists to give readers an idea about how they touch our lives. She says she had to write this book because it is close to her heart, and has been sensitive to the mistreatment of animals from the time she was a young child.

This strikes a chord in many of us from the generation who were taken to zoos and circuses as children, a well-meaning gesture from our parents and guardians. It nevertheless left some of us bewildered with a sadness we hid from our parents. We could not articulate what we felt, much less share for the risk of coming through as being “ungrateful” for all the trouble taken. We relive those emotions and moments of disquiet all over again when we read Nahal’s poems “Zoos” and “Circus of Life”. What enthralled a young poet once, doesn’t appeal anymore when she takes her son to the zoo. When her son asks ‘if they were happy’, she replies ‘happiness is temporary’. After reading the poem, we return to her first line, ‘We too live in zoos.’ In “Circus of Life”, Nahal states what we have always felt as children, ‘There is no victory in shocking, whipping animals to perform.’ What does one do with the childhood memories of seeing a man commanding an elephant to squeeze its huge body to fit on a small stool? Of tigers being tamed by a swashbuckling hero of the circus arena, cracking his whip to obey his orders? In the poem “Animals Do Not Plan for War” that show how certain ‘rules’ are followed even in the jungles, Nahal cites anthropologist and primatologist, Jane Goodall. The poem makes a pointed reference to how homo sapiens don’t even respect ‘ancient rules of not fighting after sundown.’

The book is structured with short prose-poems of less than a page that explode with strong messages often clothed in a stinging language meant to induce deep thoughts. Many of the poems come with Notes at the bottom that further validate the poet’s perspective. Not that they need any validation, but they go a long way in proving her point, or else most of us would continue with our lives, content that we have not consciously hurt or harmed animals. But stop! What about the Angoras that catch our eye, the furs that women crave for? Nahal’s “Museling” exposes the painful process of cutting off portions of a sheep’s skin and flesh near the tail end, when they are alive, for prized possessions such as Merino. And the affluent fashion industry of “Angoras, downs, alligators, snakes…” have a sordid backstory that makes one squirm.

To begin with the animals we are familiar with in India come with the weight of a value-loaded perception. The poem on elephants is aptly titled “Memory.” We revere this mammal for many things including its legendary “elephantine memory.” In a stark contrast with the ageing human community plaguedby neglect, loneliness, depression, dementia or Alzheimer, she writes ‘Elephants age gracefully, like spring flowers into summer. A close-knit herd is like a winter pullover with just the right-tight stitches. The hardening of the hide, greying together, always recalling.’ And another one, the “Elephant Tuskers” comes as a sobering influence on the wrongs done in the past. The poem is a stern reminder of why ivory is a banned product now. So we have learned to hide our once prized possessions, exquisitely carved ivory figurines of deities – Ganesh ji, Goddesses Lakshmi, Saraswati, Durga, or Krishna. We don’t display them proudly anymore, behind glass-paned cabinets. In a witty repartee to the cruel practice, Nahal states with wit and pun, ‘And because humans can think, some don’t…Shakespeare, we need some fresh oxymorons. Less morons.’

Donkeys again come loaded with cultural associations, almost like a racial memory. For some obscure reason “You donkey!” is a cuss word in Tamil. Nahal’s “Ride Me If You Must” depicting a donkey’s life is one of the most moving poems in the collection. She ‘hears’ the donkey’s thoughts through their aching feet: ‘Ropes, stirrups, saddles aren’t my friends by any stretch…I’ll continue to be ridden by countless souls satiating their desire or thrills to climb a mountain, pay abeyance, or enjoy a setting sun.’ Despite the oft-repeated line, ‘I had a donkey-load of work to clear,’ we seldom have compassion toward this over-burdened animal.

There is much awareness now about strays. In the US, some of these dogs are adopted by families as “rescue dogs.” In “Chains,” Nahal comes down hard on “Cheap, thick chains that oxidize. Erode. Twisting and twisting around a neck…” she writes about dogs chained outside homes, a practice that should be declared as “criminal.” The dogs in the so-called “foster homes” live in appalling conditions, so Nahal uses the noun as a verb in her powerful title “Please don’t foster me.” We see a sample of domestic violence in “Good Children and Good Dogs” where a tyrannical, narcissistic husband throws the rice cooked by his docile wife, coweringunder his violence. The dog and the child eat the rice. As a relief, “A Pigeon’s Sound Soothes” is a nostalgic recall of the sounds of pigeons that unravel her memories.

Nahal pays homage to the universal love of a mother towards her offspring in this collection of poems. In “A Single Mother In a city,” the narrator wishes to be like orangutan moms, or penguin moms, or elephant moms, kangaroo moms, or a ruby-throated humming bird. A lioness, cheetah or bear go by the unstated wish, “there’s nothing I wouldn’t do to protect my child.’ The male sloth on heat, who chases a new mama with the baby clinging to her breasts, is put in place by the mama who embraces her baby in “It’s Not All About Sex.” Singing whales mate gently, seeking partners even if “for a few moments.” The poet remarks on the ‘Bliss of these unions releasing ancient Akashic wisdoms.’ If only humans could learn from these sentient beings.

Nahal talks about water pollution by questioning the plight of innumerable aquatic animals living in oceans and rivers. In the poem titled, “Would You Like to Die In Another’s Trash,” she writes, ‘Confusing innocents in open, vast oceans, flowing rivers, silent lakes,’ their tummies full’ with ‘plastic, clothing, hair, nails, paper, bottles…’.

“The Story of The Endangered Himalayan Respect” is an outstanding poem about the Pangea, majestic in its movement, even as it follows the sad track of its diminishing size: ‘My respect is carried on the backs of the dwindling numbers of snow leopards, musk deer, black bears, the yaks – the untamable – and all others who remain to tell the narrative of my slowly curving, painful aging back. It’s my account. I just need to remember to straighten my spine.’

The book sustains on the range of Nahal’s style – witty, humorous, yet stingingly satirical while mocking us for our thoughtless follies. She defines her style as something ‘akin to Beat Poetry of the Spoken word’ where words and phrases are repeated for effect. Reading Animals is an expansive experience. It wakes up our slumbering collective conscience. We are larger for having read the book. In a simple line that comes straight from her heart, Nahal thanks with gratitude ‘the animals with whom we reside in this world.’ (Introduction)