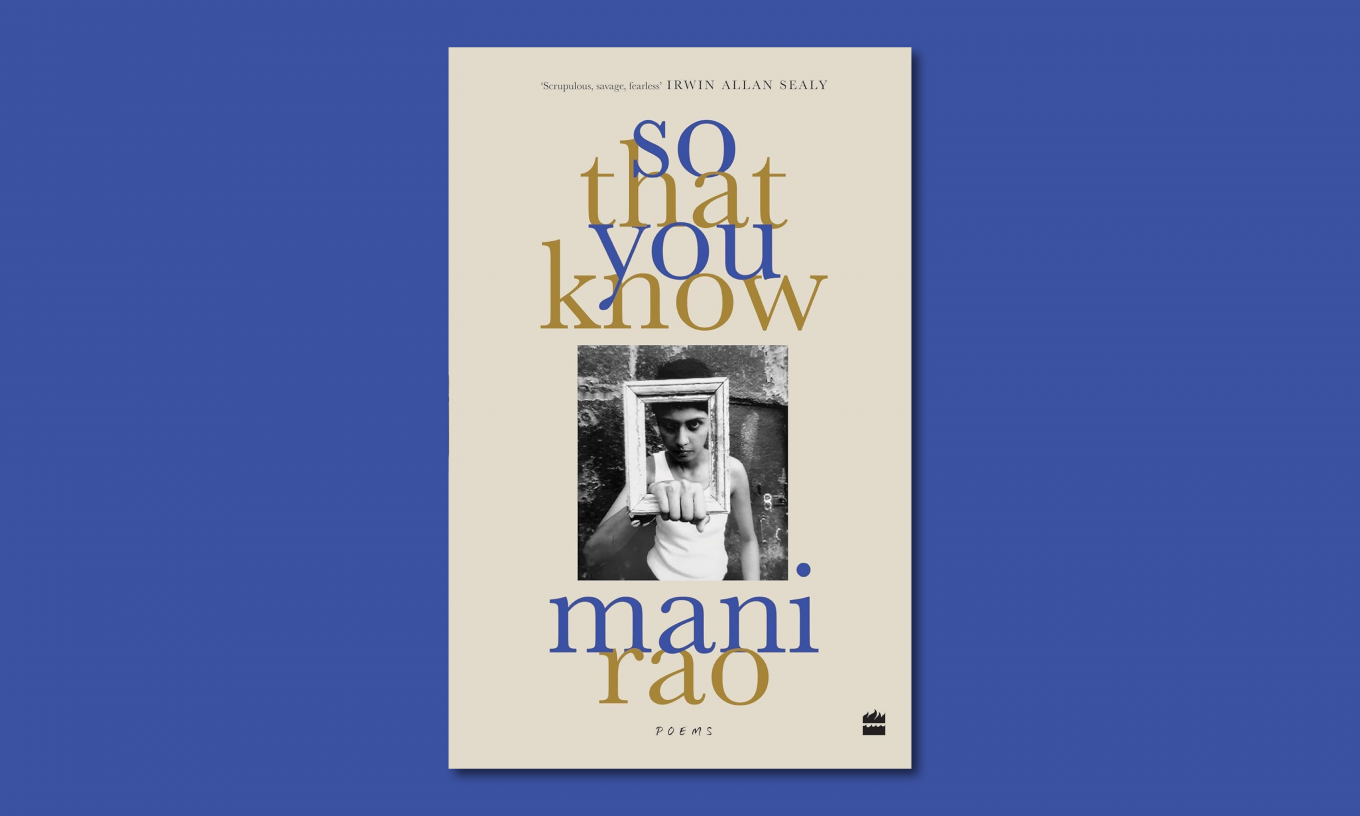

Poetry is regenerative when the act of knowing induces the poetic self to hurl into the ‘known unknown’ in search of wholeness. Sounds oxymoronic and paradoxical but this seems to be the epistemic premise of Mani Rao’s bracingly creative recent collection of poems So That You Know(Harper Collins, India 2025). The process of knowing one’s questing self witnesses a soulful trajectory of vulnerability, isolation, conflicts, power struggles, disintegration, and transcendence. What is revealed is the poetic self basking in blissful gravity and playful levity. Rao’s style of revelation is uniquely experiential in seeking the knowing self. The motif of self-knowing persists in Mani Rao’s works like “Bhagavad Gita : God’s Song” (HarperCollins 2023), “Saundarya Lahari: Wave of Beauty” (HarperCollins,2022), and “Living Mantra: Mantra, Deity and Visionary Experience Today” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019). The poems work together as an incisive and revelatory study of self-knowing. Rao is a nurturer of self-knowledge committed to fostering that awareness. If self-knowing follows an esoteric path, the language of seeking is both intuitive and abstract. Aside from the conversational immediacy, the poems testify to the polarities of additions and omissions and their mutual inextricability which gathers momentum at the level of semantics to precipitate acting out.

In the section “Echo Location”, readers tumble through a torrent and torture of diurnal realities that engender strife. The strife to untangle one’s self is a challenge where one’s subjectivity gets dissolved. Rao uses avant-garde techniques such as shock to arrest the fluidity of post-modern existence: ”The clock leaks. Drip drop dribble drip drop dribble.” The onomatopoeic pattern critiques the aleatory nature of human existence. The dramatic value of the sound pattern reflects the inevitability of drab banality. The persona wears her resentful pessimism on her sleeve: “The boatman has vanished leaving the oars and I am inflating/ unstoppably into my hollows – shoes, clothes, pen.” A sense of futility is writ large as the dismal nature of knowing unfolds; mark the multiple hyphenated phrase: “I get together sometimes, a hall of mirrors, swearing, different/ stories, playing you-know-that-I-know-that-you-know-that-/I-know.” The poem lays bare the truth that the inconsistencies that lie at the core of self-knowing are an impassioned intellectual paradox. One falls into this insidious temptation that comes in the way of self-knowing: “Unhitched you hurl in two opposite directions. Your mind speeds on, a whistle, minding nothing; your body’s best crash, I see it coming.” This cycle goes unabated as it acutely comes to terms with the human condition: “The days hatch around you feed their hurried mouths. The years open like doors, one by one they shut behind you; some softly, some bang shut.” In the process, an uncanny sense of decay sets in : ”Leave me in the garden slope, a dial tilted to the stars, on the orange trail as they roll to rot.” However, an anticipation lingers in the rhetorical question to embrace a redeeming paradigm : ”Was desire meant to be saved, kept alive, unanswered?”

Rao is irresistibly appetitive in crafting a string of provocative couplings through the extended metaphor of ‘eyes’. The persona thinks beyond the bounds of sensory experiences: ‘We burn eyes./Slippery flambéed moon on water.” On another occasion, the persona grapples with the traffic of desires: “The one star you find and pin with your eyes as I scramble for a wish.” What later follows is a volley of epigrams where eyes evoke an erratic and insistent rhythm of life, where insatiable impulses run riot: “Eyes are emissaries, soft knocks, nibs.”; “Eyes are tongues, mad riverbeds insomniac for salt.”; “Eyes are fangs, bared chisel tattooing face on retina.”; “Eyes are the itineraries of shooting stars on the trail of new disasters.” No wonder, the complex associations of ‘eyes’ may be at times beyond readers’ ken: unpredictable, intriguing, and expansive.

For Rao, self-knowing is anchored in the resurrection of language. The poet claims: “You know a language well if it does things you don’t have control over. Bring me the words without meanings, words all meanings have abandoned, sentenced to meaninglessness.” The power to reclaim is to seek the intricacies of meaning from the depths of ambiguity to save the cohort of humanity lost in the manipulation of language. The poet’s cynical humour is evident: “Monkeys, we leap from word to word, thick with meaning. / Spiders, our words are resilient webs, we make snares in the colour of air, sweet-smelling and sticky.” Readers can sense the deception of post-truth and its assault on language and meaning where the wielders of language are reduced to hype masters who trick readers into falsehood disguised as truth. No wonder, Rao leads the way through her attitude to non-compliance: “Maybe I ought to mince/ my words, toe the line/ But I don’t/ I’m a freedom fighter.”

One identifies the generous sprinkling of allusions in “I Talk to Myself- I Talk to You”. Structured as a poem-essay, it is a scholarly delight as poets like Octavio Paz, Marquis de Sade, Paul Celan, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Dilip Chitre, Wislawa Symborska, and P.K.Leung engage in a freewheeling conversation. All the poets display a dialogical disposition to deconstruct the act of knowing. If Paz’s desperation shows existential angst, Sade draws on the domain of pleasure to redeem the human condition; If Celan’s claim brings life into moral proximity with survival, Faiz is embittered but emboldened by his steadfast rejection of religious dogmatism; if Chitre strives for mystical grace, Paz stands undeterred with a forward-looking gesture. If Symborska hopes for happiness, truth, and eternity, Paz is metaphysical in his equivocation about the Nirvana-Samsara kinship. The poem ends with P.K.Leung’s longing for a world of perfection in the face of moral blindness. The conversational style of the poem presents a network of multiple significations for a hypertextual reading experience.

The stylization evident in the section ‘Living Shadows’ adds a new dimension of representation in the literary tradition of Indo-Anglian poetry. Ostentatiously expressive are the sections where Rao bolsters the privilege of images over words. The large-sized typography gains metaphysical attention due to an unquenchable striving for revelation. The poems in this section express a frantic hankering for self-expression: be it aggressively narcissistic or purely symbolic. One finds the mystical or elusive self revealed or hidden in the conversation between light and shade. Note the lines: “My shadow /comes home/ at night /Howls/at my grave/till I open/my coffin/and let him in.” In another poem, the persona says: “Living shadows/eating light/And I a hive/Vast tree/of nests and wings/shooting off”. Moreover, there is an evocation of shadows : “I’m after the plot I shadow my shadow I /slow down, dilate my eyes and shapes/ step out of the darkness.” The persona is categorical burst of assertion: “My shape holds/shadows like water” and also calculative while alluding to a mathematical formula: “…the shadow depends on a few materials” and what follows is a numerical evidence of materiality to measure self-knowing. Does the play of shadows culminate in the confession: “I’ll be my shadow” ? to foreground skepticism about self-knowing. Rao saunters out into the shadows to catch the unexplored wilderness of her selves and her states of being. One recalls the Nobel Prize-winning Mexican poet and essayist Octavio Paz’s metaphysical utterance: “The body is imaginary, and we bow to the tyranny of a phantom. Love is a privileged perception, the most total and lucid not only of the unreality of the world but of our own unreality: not only do we traverse a realm of shadows; we ourselves are shadows.” Readers might infer that this gesture is to reassure how self-knowing redeems meaning through a process of tortured conflict. The external ingenuities here are evident: typographical features, black background, line breaks, spacing to create the drama where the convergence of inner awareness responds to the divergence of the outer world.

The collection offers moments of intense recognition with the self. It unravels a passionate embrace of the self. The self lays bare an insatiable appetite and renders the act of knowing the unknown at times ineffable. Consequently, an enduring thirst is offered to readers. Does it mean that the work only caters to the elite group? Does its esoteric quality suggest an implicit challenge to the uninitiated? It should not be a deterrent to meaning-making as the work represents an ensuing drama of thought process that clouds the self in moments of crises yet edifies it in moments of deeper self-excavation as Rao concludes the collection with the yet-to-be-explored language of self-knowing where the anaphoric phrase “I want to” navigates the craving to “Know the heart’s hunger for belonging.”, navigates the desire “to sprout in a blink”, and navigate the desire in a laconic way to linger “at the threshold of the world’ confirming her full-throated affirmation: “but an age is yet to be lived/ before tomorrow”. In the process, writing is instrumental as Rao says: “They(writers) see to suffocate when they don’t write. Language is the air they breathe, the atmosphere they live in, and atmosphere stays bound, to the earth.”

So That You Know challenges readers to look within and beyond. It offers no sense of closure as Rao claims: “You keep dissolving but you never finish your book, it is a roaring thirst, the jaws of a lion ajar roaring without stop.” It also gives readers a glimpse into Rao’s process of writing and collective perception in articulating moments of self-knowing. It invites readers to unveil the spectrum of life, examined and unexamined! Structurally, the work is a breakthrough in its inventiveness and strategic modes of expression predicating on the truths of self-knowing and allowing access to readers to internalise impressions, psychic and physical, in crystallising interiority so that you know!