Introduction

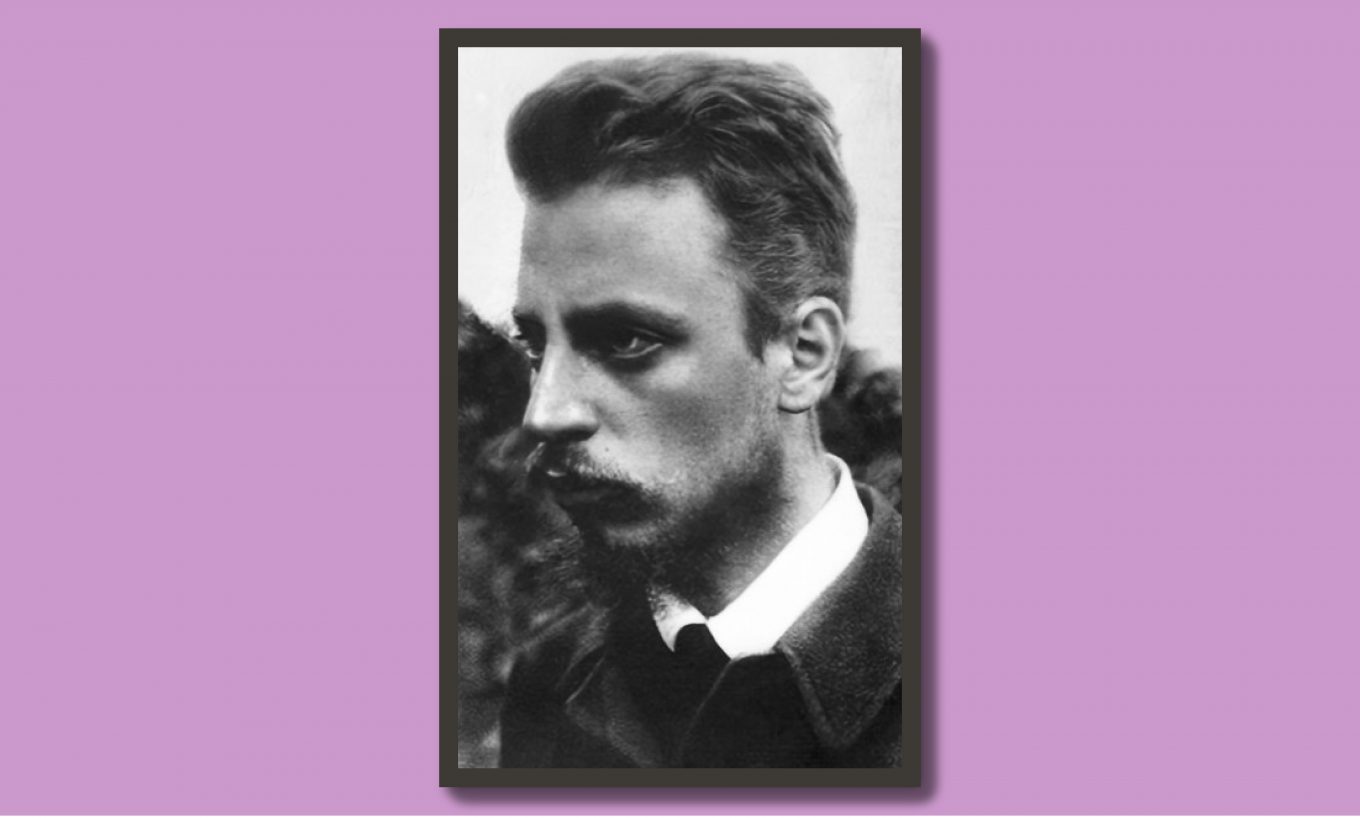

I remember that moment more vividly than most things that have happened in the thirty years since, as if it were yesterday. The chaos of the Delhi World Book Fair swirled around me – voices, the shuffling of feet, the rustle of countless pages – when my eyes fell upon a book I had never seen before: The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by Stephen Mitchell. I did not know the name then, had never read a line of his verse. Almost idly, I opened it. Page 91. ‘For the Sake of a Single Poem’.

As my eyes moved across the lines, the din around me dissolved. The crowded fair receded; it was as though I stood in a silence vast enough to contain only me and that poem. The page seemed to hold within it the essence of poetry itself – its secret, its culmination, its impossible standard.

By the time I reached the final lines – ‘And it is not yet enough to have memories. You must be able to forget them when they are many … Only when they have changed into our very blood, into glance and gesture, and are nameless … only then can it happen that in some very rare hour the first word of a poem arises in their midst and goes forth from them’ – something inside me had shifted irreversibly.

At that time, I still thought of myself as a poet; I had even brought out a slim book of verse under the aegis of Prof. P. Lal’s Writers Workshop. But Rilke’s words undid that illusion in a single stroke. They made clear to me what poetry could be, and how far away I stood from it. For more than twenty-five years after that day, I could not bring myself to write another poem. If ‘For the Sake of a Single Poem’ was the benchmark, I knew I could never measure up.

Rilke and My Own Becoming

Reading Rilke is like reading myself, though in a language I could never have invented. There is the sheer music of his language. Even in translation, his words fall with the authority of something eternal. When I read Rilke, I feel as though someone has entered the deepest chambers of my solitude and spoken aloud what I hardly dared admit to myself. His poetry is not something I ‘study’. It is something I live with, something that rearranges the way I see my own existence. He does not speak at me, but with me, gently, urgently, as if he has known the precise shape of my longing all along.

What draws me most is his refusal to separate beauty from terror. He insists that life is indivisible, that we must accept its contradictions if we are to live fully. When he writes, ‘Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. Just keep going. No feeling is final,’ I feel my own fears soften. So much of my life has been spent resisting pain, mourning what I cannot hold, regretting what slips away. Rilke teaches me that resistance only deepens the wound. To live is to open myself, even to what hurts. That is not weakness but a strange kind of courage.

Death, in his poetry, becomes less of an enemy and more of a secret partner. I have always flinched from the thought of endings, from the fragility of all that I love. But when Rilke speaks of death as a transformation, as the ripening of what life has prepared, I begin to see mortality as a completion. It makes my days more urgent, my moments more precious. He whispers that even my fear of loss can be turned into tenderness.

And then there is solitude. I have often treated my solitude as a deficiency, as proof that something in me is incomplete. Rilke reverses that entirely. He teaches me that solitude is not emptiness but a space of growth. It is in solitude that love matures, that art is born, that the soul takes its true shape. When I am most alone, his words remind me that I am not abandoned but simply being prepared – for love, for depth, for a fuller encounter with life.

Rilke’s God is not the God I grew up fearing, not the God of rules and distance. His God is unfinished, always becoming, always waiting in the silence. When I read The Book of Hours, I feel that I, too, am allowed to pray without certainty, to doubt and still belong. This is a faith I can inhabit: not dogma, but dialogue. A God who listens in the pauses, who hides in the ache of longing.

What astonishes me most is how current his voice feels, even after a century. In an age where everything urges me towards noise and speed, Rilke tells me to slow down, to wait, to trust the hidden work that takes place in darkness. He tells me that my unfinished questions are themselves a form of living. That no resolution is final, that becoming is endless.

His influence on me is not abstract. It is intimate. His poems are the companions I turn to when I cannot make sense of myself. When I feel broken, he tells me my cracks are where life enters. When I feel abandoned, he tells me solitude is the place where I grow roots. When I feel afraid of endings, he tells me that death itself is a flowering.

This is why Rilke endures. Not because he offers comfort, but because he offers truth, a truth that does not simplify but deepens. He does not erase my longing; he teaches me to inhabit it. He does not silence my fears; he coaxes me to listen to what they conceal. In his words I find not escape, but a homecoming.

Autumn

Lord, it is time. When I read the line the first time, I stopped at it and closed the book. There was no way I could go any further without letting the commanding, almost prayer-like invocation seep into me. Reading any further would be almost disrespectful to the quiet majesty of that line. It immediately sets the tone for the rest of the poem: summer’s long ripeness has ended, and the world stands at a threshold. In that moment, autumn is not simply a season but a reckoning, a turning of life itself towards maturity, decay and reflection. Rilke’s imagery of fruit swelling, vines heavy with wine, and shadows lengthening brings alive the richness of harvest while hinting at mortality’s quiet approach. The poem captures the fleeting passage of time and the existential truths hidden within seasonal change

What makes the poem unforgettable, however, are its closing lines: ‘Whoever has no house now, will never have one. / Whoever is alone will long remain so…’ Here, Rilke moves from the natural world to the stark human condition. The shift is devastating: autumn becomes not only the year’s twilight but also a metaphor for solitude, for the inevitability of loss and incompletion. In its brevity, ‘Autumn’ balances the beauty of ripening with the ache of transience.

Fears

I often go to this poem when I am confronted with the knowledge that every time I have craved a return to childhood, I have realized that it comes back as difficult as it used to be – that the nostalgia for the ideal childhood is nothing but a chimera, and that, as he says, growing up has been entirely purposeless. ‘Fears’ is one of those rare poems that illuminates the hidden undercurrents of childhood – those strange, irrational terrors that adults forget or dismiss, but which shaped our first sense of existence. What makes it resonate is not only the specificity of the images but their uncanny power: a breadcrumb that might shatter like glass, a button larger than one’s head, a thread sharper than steel. Each detail captures the disproportion of a child’s imagination, where the ordinary is magnified into dread, and the world feels charged with menace.

The poem’s genius lies in how Rilke restores the authenticity of these fears. They are not mocked but dignified, given the weight of lived experience. By cataloguing them, he dramatizes the helplessness of childhood, an age when one cannot distinguish between inner phantoms and outer threats. The fears become metaphors for existence itself: the fear of betraying oneself, of everything breaking ‘forever’, of the unsayable that words cannot contain. Childhood here is not a time of innocence but of raw vulnerability.

The closing lines deliver the poem’s deepest sting. The poet has ‘prayed to rediscover’ childhood, and it returns, but as difficult as it used to be, full of the confusion and dread it always nursed. Growing older, he says, ‘has served no purpose at all’. This realization resonates universally: adulthood does not free us from fear but often disguises it. In recovering childhood fears, Rilke exposes fear as fundamental to being human, timeless and unresolvable.

The poem reveals what lies beneath memory and nostalgia. It resists sentimentality, presenting childhood not as golden but as a crucible of terror. Its rhythm – part incantation, part confession – pulls us into that primal world where the smallest things are overwhelming, and where the deepest truths of our lives are bound up in what cannot be explained or overcome.

Go to the Limits of Your Longing

If ‘Fears’ mocks our nostalgic longing for childhood as misplaced, ‘Go to the Limits of Your Longing’ is inspirational. When I lost my job in the middle of the pandemic and was staring at a future uncertain – and every time since then, whenever an experience appears overwhelming – I go back to the line that distils life into its starkest truth: Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror. It is one of his most luminous affirmations of the human condition. Both beauty and terror are essential parts of existence and to understand that is to embrace life in its wholeness.

Blending spiritual intensity and startling simplicity, Rilke speaks in a voice that feels both intimate and transcendent, as if the words are whispered directly to the reader from some place beyond. The premise – God speaking to each of us as he sends us into the world – provides a metaphysical frame, but the poem’s power lies in its profoundly human encouragement. Rilke does not offer the comfort of escape or avoidance; instead, he insists that one must undergo all of experience, without judgement.

Likewise, ‘No feeling is final’ resonates because it is both consoling and liberating. It reminds us that despair, grief, even joy, are all transient, and that this impermanence, far from diminishing their significance, is what allows us to keep moving forward. The call to ‘go to the limits of your longing’ urges us towards courage: to risk, to yearn, to inhabit fully the expanses of our desire and potential. There is nothing tentative here – only an insistence on intensity, on embodying the divine spark by living passionately.

The closing gesture – Give me your hand – is tender, grounding the lofty spiritual charge in a simple human connection. It reassures us that though life is serious, even grave, we are not abandoned. The poem’s greatness lies in this fusion of transcendence and intimacy: a vision of life as both sacred and fragile, urging us never to shrink from its fullness.

Put Out My Eyes

This poem is marked by an astonishing surge of energy, a declaration of the indestructibility of love and vision. What makes it so vivid is the relentless piling up of images, each more extreme than the last, as if the poet were testing the very limits of the body and then surpassing them. It speaks to something primal in us – the instinct to reach for what we love or believe in, no matter what constraints the world imposes. The poem burns with defiance: tear away the senses, break the limbs, still the heart – yet nothing can sever the bond between self and beloved.

The intensity comes from its rhythm: short, forceful clauses that strike like blows, mirroring the violence of the mutilations they describe. But instead of despair, each blow becomes a transformation. Eyes gone? The imagination still sees. Ears sealed? The spirit still hears. The body is not diminished but transfigured; love and presence become larger than flesh. This movement is what gives the poem its elemental vitality. It is not resignation but a hymn to the irrepressible force that connects being to being.

At the core is the idea that the deepest truths of love, faith, or devotion are not dependent on the fragile mechanisms of the body. The heart and mind become instruments beyond anatomy, capable of carrying and holding the beloved even when every physical faculty is stripped away. The final image, of carrying the beloved in the bloodstream itself, is both visceral and exalted: love as lifeblood, circulating irrepressibly through every vein. In its refusal to let go of what gives life meaning, even when everything material is taken away, this is Rilke at his most elemental, fusing violence and tenderness into pure, unstoppable affirmation.

Requiem for a Friend

Written in memory of the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, this is one of Rilke’s most profound meditations on death, art and love. What makes it a great poem is the way it fuses grief with metaphysical questioning, transforming personal lament into universal reflection. Rilke does not merely mourn Paula’s death; he wrestles with the meaning of her departure, her return as a ghostly presence, and the unfinished dialogue between the living and the dead.

Unlike a detached elegy, this is a direct, urgent conversation with the dead. Rilke alternates between tenderness and accusation: he longs to comfort her, yet reproaches her for disturbing the order of transformation that death demands. The result is a poem that dramatizes grief as a dialogue, charged with the uncanny presence of the departed.

The poem’s philosophical weight deepens as it moves from mourning to a meditation on love. Rilke’s insistence that ‘we need, in love, to practice only this: letting each other go’ crystallizes the poem’s insight: love is not possession but freedom, and even in death, this freedom must be honoured. It refuses consolation, yet arrives at a truth about art, love and death that transcends the particular loss. In its vastness and intimacy, it remains one of Rilke’s most haunting achievements.

You Who Never Arrived

This poem speaks to me because it addresses an absence that is more alive than any presence. The opening line – ‘Beloved, who were lost from the start’ – strikes with the force of a wound that has always been there, a recognition that what we yearn for has always been elusive, always beyond reach. And yet, the yearning itself gives life its depth.

When Rilke writes, ‘Beloved, you who are all the gardens I have ever gazed at’, he captures that aching truth: that our desires, our ideals, our search for beauty, all find their form in the figure of the unseen beloved. The beloved here is not only a person but also a symbol of the eternal, the unattainable, the radiance just beyond our grasp. Every landscape, every tower and bridge, every fleeting turn of a path becomes charged with their presence.

The most haunting image is of mirrors ‘still dizzy with your presence’. This speaks to how memory and desire leave behind an echo, a residue that unsettles and confuses. We are startled, as if the world itself still remembers what we missed, and reflects back our solitude. What resonates is how Rilke transforms absence into fullness. The beloved never arrives, and yet the anticipation, the shadow, the lingering trace fill the self with vast images and meanings. In a sense, it is the not-arrival that creates the poem’s intensity.

The poem mirrors the way love, loss and longing shape a life: never fully answered, but always expanding the soul’s horizon. It speaks to the mystery that perhaps what we seek has always brushed past us, leaving us forever in pursuit.

In Conclusion

In returning to Rilke across the years, I realize that what began as an encounter at a crowded book fair has evolved into a lifelong apprenticeship. His poems have accompanied me through my own seasons – the ripening, the fear, the solitude, the bewilderment, the unexpected grace. They have shaped not only how I read but how I live, teaching me that the task is not to master experience but to surrender to its transformations. In his lines, I have found not a philosophy but a way of being: porous, attentive, courageous in its vulnerability.

As we mark his 150th birth anniversary – and a century since his passing – I feel more than ever that Rilke is not a poet of the past but of the ever-unfolding present. His voice continues to open spaces within me I did not know existed. Perhaps that is his greatest gift: he makes me a beginner again, willing to listen, to wait, and to let life happen in all its difficult radiance.