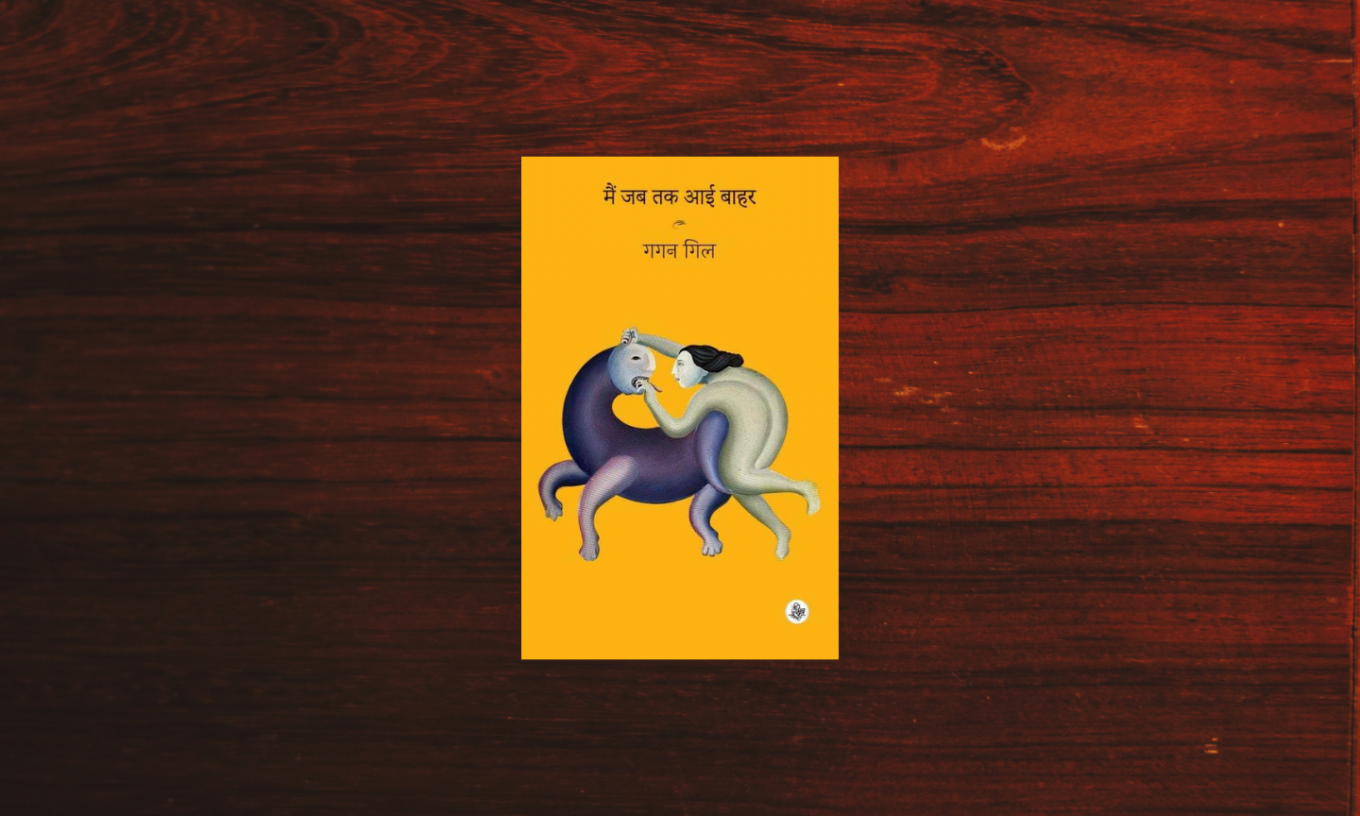

Title: Main Jab Tak Aai Baahar

Author: Gagan Gill

Publisher: Rajkamal Prakashan

Year of Publication: 2024

Gagan Gill’s poetry: The inner praxis of ‘baahar’ (outwardness)

Gagan Gill’s 2024 Sahitya Akademi Award-winning book of poems, “Main Jab Tak Aai Baahar” ( By the time I came out) was initially published by Vani Prakashan(New Delhi) in 2018. I am fascinated by the word ‘baahar’(outer) and its consequent implications that disarmingly intrigue readers through a thicket of longing, denial, and revival.

The poetess, emerging from the stillness of her meditative mudra, undertakes a number of subtle raids across the borders of meaning where life appears as a cluster of perplexing riddles. The eponymous poem Main Jab Tak Aai Baahar ( By the time I came out) begins with a smarting twinge of culture shock in the face of a world gone hideously awry. Poetry, caught in the crossfire between a disquieting society and a discerning poetic self, comes to the fore in readers’ consciousness to reconcile the two realms of knowing. Her poetry of quest is a musical cadence rising from the fog of disorientation. The poet’s persona is prompted to venture into inward expeditions. The key word ‘baahar’ (outer) offers not only a possibility of renewal but also a process of sublimation. It is a buffer against the moribund instincts of life by beckoning the ‘baahar’(The outer world) as a catalyst to unravel the inner world and transcend the threshold of consciousness.

Let’s look at the titular poem. The poem opens with an overwhelming sense of angst about language. The poet’s emphatic declaration in the phrase ” Badal chuka tha marm bhaṣha ka”

(The essence of language had changed) is a caveat against the decay of language and the assault on it. It provokes questions about meaning-making and its methods. Does it signal to slough off traditional paradigms of language or foreshadow the monopoly of a dominant language in exercising its ostensible power to chip away at a minority language? The poet seems to be in search of a deeper affirmation of language and its role in mitigating human crises. The poem leaves the mind enveloped in sombre musings. Sombre because the poet uses the metaphor of ‘lock’ imposed on temples to insinuate the arrogance of religious dogmatism and its political nexus. The ‘lock’ is an extended metaphor reigning supreme in “cities, hearts, lips”. This unbridled downslide to moral emptiness puts the conflict between the inner and outer world into full swing, to which readers are given mediated access. While readers sense the nature of vulnerability and fragility, the poet recognises the need for a repository of energy to withstand the inevitable decline: linguistic, existential, and ethical. The energy derives its cognitive closeness from the poet’s faith in the visionaries like Tagore and his sense of global citizenship in moments of stagnancy.

What is redeeming is the poet’s self-assurance: “Sudhar rahe honge/ duniya ki ghari” ( You must be fixing the world’s clock)in the poem “Abhi main pehchanti hu tumhe’(I know you now). The poet as watchmaker is reminiscent of the world of Tagore – earth-bound and heavenward. This self-assurance emerges from the poet’s faith in rebuilding a society grappling with emptiness, more metaphysical than cultural and linguistic. What is in disorder and dissipation demands cohesion- a cohesion to seek meaning. The metaphor of the poet as watchmaker is profoundly redemptive. The poem is a poignant recognition scene that alludes to the poet’s personal memory unfolding the inner world through a meditative sense of outwardness to catch transformative vibrations.

The fear-stricken persona in the poem “Ek gau mere bhitar hain”( There is a cow inside me.) confronts the epistemic and representational articulation of her angst-ridden existence. This horrifying crux, which represents the plight of the marginalised in India, compels an invocation of the past where the ‘besieged’ nation had witnessed and continues to witness a magnitude of communal carnage, laying bare the vitals of a fractured democracy.

At the end of the poem, the persona is paralysed with fear: “Hum dono ko katne ka dar hai/ bachne ka dar hain.” (We both fear being slaughtered / We both fear being saved.) The motif of the cow and the lingering fear of being slaughtered opens up the stinking reality of today’s moribund civilization. Returning to the fear of the loss of language, readers are provoked to challenge the limitations or inadequacies of language and claim the necessity of a language to recount the relentlessness of gratuitous violence. Is the poet seeking a language to heal the trauma of our times? Is the poet trying to craft a language capable of narrating the unnarratable being uncannily grotesque? Is the poet striving for a tantalizing anticipation of an idealistic world of cultural pluralism? Is the poet hinting at a tragedy, the tragedy of verbicide, implying suppression or censorship of language in a regime of outright majoritarianism? Perceptive readers will wander along the fringes of these provocative questions.

What carries language beyond this fear-dripping impasse and moral stagnation is the longing for a key to redemption. The poet’s scepticism in the wake of stagnation through the metaphor of a ‘key’ implies the need and urgency of a language where the poet becomes an indispensable intermediary, enabling the sinking humanity to preserve its diminishing integrity. Language, as an agent of denunciation, forges the truth of a cultural revival to ‘unlock’ the shrines, the cities, the hearts, the lips as the poet laments: “Taale padhe they tamaam shahar ke / dilon par / hothon par”( Locks had been placed upon the whole city —

on hearts, on lips.” The anti-climactic series from the domain of faith to the discovery of creative instincts and human awakening defines the poetic vision of Gagan Gill that calls for a re-visioning of the nature of language. Her poetic vision, resistant to hegemonic truths, nourishes radical knowledge, offering a possibility of renewal to redeem the human condition.

Much of the internal dynamic of Gagan’s poetry is sustained by the enigma of mediating a world where speech is suspended in the evocation of thought, some in harmony and some in conflict. What is left unsaid is mystical, inviting a sublime unveiling through readers’ metaphorical gaze. Cannot her poetry be called a meditative search for the fullness of utterance? The question invokes the intellectual legacy of Tagore’s modes of cognition and representation. To read this collection is to expand the landscape of loss and longing in negotiating Tagore’s cosmopolitan vision of humanity and his intellectual expedition of knowing.

The poems in the collection betray a lingering sense of incompleteness as they transition between fragments of images. In the section ‘Swapn ke baahar’ (Beyond the dream), the poem ‘Is tarah’ ( In this way) employs the metaphor of a journey as a passage from nagging self-doubt to growing self-assurance. To trudge uphill is to discover the beauty of lyrical tenderness in “tabhi chattan me se jhankte hain nanhe neele phool”(a tiny blue flower peeks out from the rock). As the sober realisation of life’s enduring struggle dawns on the persona, the journey culminates in a solitary encounter with one’s tottering self till it feels emboldened by the presence of nature, mighty in its solitary grandeur. What steers the searching self through rocky terrains is the inward urge to surrender with abandon.

In the poem “Titli ne kaha” ( The butterfly said), the tenderness of the butterfly’s plea :”Bageecha yu hi rakhna” (Keep the garden as it is) is juxtaposed with the poet’s sense of despair over her inability to tame the ruthlessness of anthropogenic actions . The poem ends with a sombre augury of a fractured future where the butterfly’s ardent exhortation succumbs to ethical laxity in stemming the tide of planetary crisis.

In the poem “Kabhi kabhi apna sach” (Sometimes our truths), the poet does not assume a didactic tone in her empathetic outpourings; rather, the singular voice of truth is pitted against the echo chamber of moral bankruptcy: ” Dho lena chahiye purana vastra/dhoop me sukha/ rak lena chahiye tahakar/ ki jarjara jata hai pare-pare/ bandh rakha vastra” (The old garment should be washed, /laid out in the sun to dry,/for if folded away it grows frail.” Does it not create a kinetic intimacy with the self? The poem evokes a revisiting of memory to unearth the residues of internal void and inner recesses that lie locked in an intimate embrace. This, it appears, is Gagan Gill’s striving for internal harmony.

Gagan Gill’s poems engender a profound sense of restlessness that shatters the silence of her artistic poise. Her self-reflexive poetry renews consciousness by juxtaposing the repudiation of the politics of fragmentation with the affirmation of the need for inner renewal. The collection is replete with inherent duality and emerging duality – if the former is about the self, the latter is about society and its apparatus. On both fronts, the poet underlines the nature of confrontation – both personal and political to arrive at an unwavering vision that induces and galvanises deeper interpretations at a time when relentless violence gnaws at the roots of the cardinal values of humanity. Gagan Gill consigns her poetical labours to the unfolding of the interior (bhitar) that has been relegated to the nether side of our ontological consciousness where the relationship between meaning and reference stands incommensurable with existence and the quest for truth.