In English, the word “man” can refer to all humankind, while “woman” is relegated to a position secondary to man. Patriarchal society has constructed woman as the Other, objectifying her and disregarding her subjectivity. This notion traces back not only to linguistics but can also be found in religious and literary texts across history. In the Bible, Adam, as a man, is created directly by God, whereas Eve, as a woman, is formed from Adam’s rib. In Corinthians, it is written, “Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience as also saith the law. And if they will learn anything, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church” (KJV, 14, 34-35).

Milton’s Paradise Lost further defines Adam and Eve’s relationship as one of dominance and subordination: “Not equal, as thir sex not equal seem’d; /…/ Hee for God only, shee for God in him” (Milton, 296 & 299). These examples highlight how, throughout the long history of human civilization, female have been viewed as the Other rather than as autonomous beings. As Simone de Beauvoir insightfully observes in The Second Sex, “She is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other” (Beauvoir, 265).

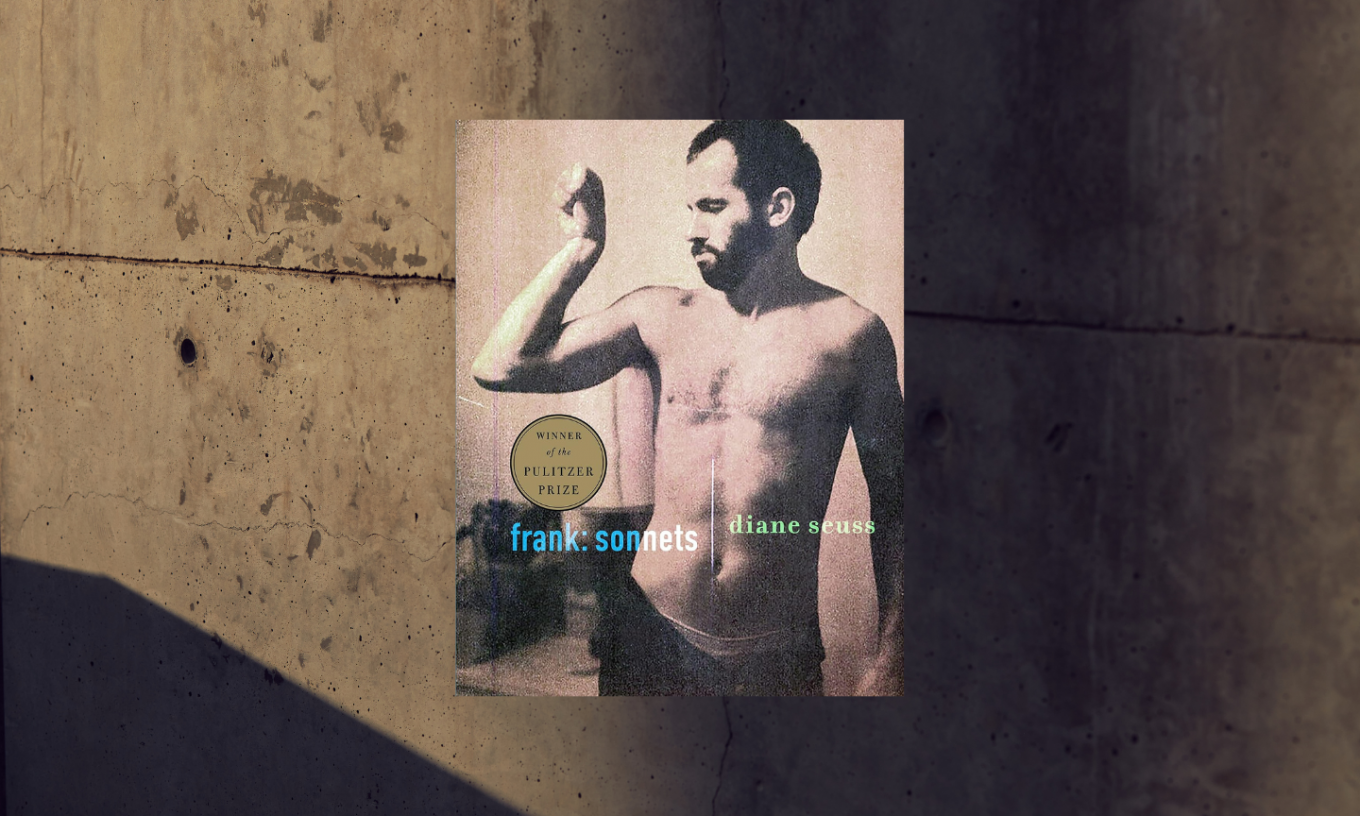

In frank: sonnets, Diane Seuss deconstructs and reconstructs the sonnet form. Through this enduring literary form, one that has thrived since Shakespeare, Seuss writes with directness, frankness, sincerity, and intimacy, adopting a style that feels almost memoir-like or autobiographical to convey a deeply personal narrative. Her narrative touches on taboo literary themes, including abortion, sex, sexual assault, and death. By breaking these taboos, Seuss, much like her modifications to the traditionally formal and solemn sonnet structure, expands the boundaries of both narrative and the sonnet form. In this collection, Seuss proclaims a reclamation of female subjectivity, rejecting the notion of being an adjunct to anyone or anything, standing solely as an autonomous individual.

In the opening poem of this collection, Seuss sets the tone for the entire book. The poem begins with two highly vivid lines recounting the speaker’s journey to Cape Disappointment. Following this, in lines 3 through 6, Seuss employs multiple repetitions of “pee”: “I pee and then / I have to pee and pee again” (Seuss, 3). Through her choice of low diction and repetition, Seuss openly addresses bodily desires without reservation. Freud, in The Interpretation of Dreams, introduces the concepts of the id, ego, and superego, asserting that the id, which resides in the unconscious, “is the real psychic” (Freud, Dream, 147), driven by instinctual impulses and physical desires. By directly depicting these physical desires, Seuss avoids being relegated to the position of the Other, asserting her subjectivity and selfhood as speaker and female.

The speaker then mentioned the renowned poet Frank O’Hara: “I’m a little like Frank O’Hara without the handsome / nose and penis and the New York School and Larry / Rivers” (Seuss, 3). By drawing a parallel to O’Hara, the poet deepens the poem’s intimacy, making it feel like a warm conversation with a familiar friend or family member. This reference also nods to the double meaning of the collection’s title, frank, which both pays homage to O’Hara and connotes candor and directness. In likening herself to O’Hara, the poet emphasizes gender, with “handsome nose” and “penis” as distinctly male attributes. Here, by rejecting these masculine symbols, Seuss further asserts her own female subjectivity. If O’Hara were a woman, he too would undoubtedly, like Seuss, “search for beauty or relief” (Seuss, 3).

In “He said it bummed him out his dick didn’t work anymore,” Seuss addresses sex and gender even more directly. The poem’s opening line plainly expresses a man’s fear of losing his penis, alluding to Freud’s theory of castration anxiety. Freud suggests that the penis symbolizes power, leading post-pubescent males to experience castration anxiety, while females supposedly develop penis envy. This inherent biological difference, Freud argues, gives female a “weaker superego” (Freud, Psychological Consequences, 4). Seuss critiques this sexist viewpoint, responding, “But it was never about dick for us” (Seuss, 92).

The first two lines establish a raw, conversational tone for the poem. Throughout, Seuss highlights differing perspectives between the speaker and her partner regarding their relationship. To him, sex itself is central. Pop culture images like “I Love Lucy,” “Dyke Van Dick,” and an “existential cowboy” suggest a fluid, performative self-presentation where his charisma radiates outward, at the cost of sacrificing deeper personal connection. The speaker, however, doesn’t agree: “But that / wasn’t how it was for us” (Seuss, 92). Her introspective lines to the relationship, “Did I perform for him. I knew no other way” (Seuss, 94), hints at women’s oppressive roles in relationships, often forced into the role of the Other, while also marking an awakening of her female self-awareness.

At the poem’s end, the partner comments on the changes in her body after childbirth: “Di / your body changed” (Seuss, 94). The speaker angrily retorts, “Jesus / Christ. What do you want from me. What did you ever want from me” (Seuss, 94). Seuss used colloquial, emotional language to create a confessional, emotionally raw moment that reveals partner’s insensitivity or inability to understand speaker’s experiences, underscoring the habitual objectification of female in patriarchal society and further challenging Freud’s essentialist opinion on reproductive worship and the innate differences between sexes.

The critique of male objectification of female also appears in “The famous poets came for us,” but here, Seuss expands her critique from personal experience to collective memory. Using the first-person plural narrative perspective, she emphasizes that the experiences described in the poem are collective and universal. In line 3, Seuss skillfully captures the power dynamics within the poem: “but either way we learned to call them beautiful” (Seuss, 57). She compares the poets’ predatory behavior to “honeybees to hyacinths” (Seuss, 57), creating an ironic effect by juxtaposing the ugly act of harassment with the image of bees, which are typically seen as beautiful and beneficial to nature.

In the recurring line “they came for us,” Seuss intensifies the physical violation in line 4 with the variation “they came in some of us” (Seuss, 57), underscoring the bodily exploitation involved. The line “unreadable but fuckable or readable and fuckable” (Seuss, 57) emphasizes the objectification of female, reducing them to Others based on superficial physical standards rather than literary worth. By using “fuckable”, a colloquial, informal term, to describe women, Seuss highlights the power imbalance and male disdain toward female.

In line 9, the bee simile reappears: “like honeybees they dumping their load / of gold” (Seuss, 57). This image sarcastically portrays male exploitation of women; unlike the mutually beneficial process of pollination, here it is one-sided and harmful. The famous poets pursue their desires, leveraging power disparities to take whatever they want. Seuss lists those deemed “unfuckable,” underscoring how women are judged, categorized, and dismissed based on appearance or traditional male-centered values, further reinforcing the female’s objectification as the Other. Michel Foucault argues that subjectivity and Otherness are largely formed by societal discourse, which imposes values and beliefs through power dynamics. He notes that “disciplinary power, on the other hand, is exercised through its invisibility” (Foucault, 25). Through recounting the collective memory of power abuse in the literary world, Seuss confronts the disciplinary structures Foucault describes, creating a female discourse in her own voice that resists societal conditioning. Seuss’s frankness about sex throughout this poem and the entire collection also reflects Foucault’s assertion in Histoire de la sexualité that sexuality, and all bodily desires, serves as a tool for realizing subjectivity. The taboo surrounding sex is a means for those in power, here men, to reinforce the Othering of women. By breaking these taboos, Seuss challenges societal conditioning, using sexual openness as a way to assert female subjectivity and resist social discipline.

In the penultimate poem of this collection, “My tits are bruised,” Seuss delves further into the relationship between sex and female subjectivity, illustrating that breaking sexual taboos does not contradict rejecting male objectification in sexual encounters. The poem opens with the speaker’s injured body, “My tits are bruised as if I’ve been with a rough lover but I have / not been, not today” (Seuss, 129), establishing a tension between desire and restraint and hinting at intimacy tinged with violence. A pear emerges as the central image of the poem, described as “hard enough to pound a nail into a re-enactment crucifix” and “dick-hard.” This juxtaposition of religion and sexuality clearly defies taboo, while the pear’s ripeness embodies both sensuality and unease. However, the speaker refuses to eat it: “the more it wanted my / teeth in its hide the more I dodged it, I’d lost all respect for it” (Seuss, 129). The pear is left to rot, symbolizing the speaker’s assertion of sexual agency that female participates in sex from free will rather than as an object of male desire, claiming the subjectivity of female in sex. The final line, “I’m worried about these bruises and who will hold me when I die?” (Seuss), is a confession of the poet’s vulnerability, adding intimacy and frankness to the poem.

In frank: sonnets, Seuss reshapes female subjectivity through candid exploration of power dynamics, gender, and sexuality, combined with confessions of vulnerability. Moving from personal experience to collective memory, Seuss consistently rejects the objectification of women and the power-laden implications of sexuality under traditional social conditioning. She gives voice to the exploited and disciplined, standing firmly against essentialism and sexism, echoing Beauvoir’s assertion that “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” (Beauvoir, 301). Through poetry, Seuss examines the violence and exploitation exerted by men as the Same against women as the Other in terms of body, gender, language, and culture, exposing the hegemony and oppression within the process of Othering. In doing so, she challenges and subverts the binary gender system, achieving a liberation of the Other and reclaiming female subjectivity.

***

Work Cited

“KJV Version of Bible.” Bible Gateway, www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1%20Corinthians%2014&version=KJV. Accessed 7 Nov. 2024.

Milton, John. Paradise Lost: A Poem, in Twelve Books. The Author John Milton. 1711.

Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Wordsworth Editions, 1997.

Freud, Sigmund. “Some Psychological Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction between the Sexes.” The Psychoanalytic Review (1913), vol. 18, 1931, pp. 439-.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage, 2012.

Beauvoir, Simone de, et al. The Second Sex. Knopf, 1953.

Seuss, Diane. Frank: Sonnets. Graywolf Press, 2021.