Translator’s Note:

While translating the Kashmiri vaakhs (verses) of Lal Ded into English, I found two unequal worlds colliding. I had to resort to inventiveness while making sure that the essence of the original, which is rooted in Kashmir’s indigenous mystical and philosophical tradition, is retained, and remains intact to the greatest extent possible. While preserving the densities and complexities of the original verses, I reconstructed their structural, syntactic, and linguistic intricacies. As a result, a narrative frame and a recasting device took shape. You will see that the mythological references of the original remain intact.

In the process, the vaakhs, as they sound in original Kashmiri, lost their punch. A translator is merely a negotiator and mediator between the poet and her readers. For me, this translation is a performance to bridge the distance between two cultures and languages. Through these shadows, I have tried to give Lal Ded citizenship in another language. I have translated 161 verses from what is available of Lal Ded’s 200-plus verses.

***

Sculpting Memory and Time

Translating Lal Ded: My Father’s Unfinishable Project

Siddhartha Gigoo

Summer of 1993

The Bhatiyal house

Barrian, Udhampur

J&K State

Pa is back from a long walk. Babi, my grandmother, starts worrying if Pa doesn’t return at his usual time. Today, when he returns, he isn’t alone. He has brought two labourers with him. A handcart stops outside the gate of the house where we live on rent. Pa instructs the labourers to get started. The two men lift the trunk of a tree and carry it into the lawn. ‘Not here. Take it upstairs,’ says Pa, pointing to the terrace.

The labourers carry the tree trunk to the makeshift studio Pa has set up on the terrace. It isn’t finished yet. Babi and Ma are shocked at the sight of the log being carried upstairs. So far, Babi and Ma have dealt patiently with Pa who has got into the habit of bringing back small pieces from his long walks every day. Branches and twigs and stones. But this time, Pa has brought along half a tree.

‘What’s next?’ they think. ‘An entire tree?’

Pa doesn’t care to explain. Driftwood is his best friend now. His preferred company, along with his tools—chisels, mallets, hammers, a file, blades, sandpaper, varnish, paint, and paintbrushes. Spending some part of his day in the studio has become a rite.

But Babi isn’t angry or upset. She knows it is for her son’s good. It is the only thing that keeps Pa from crying, saving him from the depression that had him in its grip last year. So far this sculpting business has worked. Pa doesn’t cry much. He doesn’t talk much either. It’s like he prefers to speak through his creations.

A few shapely models already peek out from the pile of wood. I can’t take my eyes off one.

‘Is this your first finished work?’ I ask Pa.

‘Far from being finished, it demands more work…’

‘What do we call this piece?’

‘How about An Exile?’

His body is crooked now. Exile seems to show its effects on him.

‘He is all of us,’ people say when they look at him. He takes after half a million Kashmiri Pandits who are in exile now.

There’s a Christ on the crucifix and a dancer too. Both look unfinished.

***

Summer of 2023

Jammu—Faridabad

Ma and Pa divide their time between two homes. One in Jammu and the other in Faridabad.

‘Do you remember the time when all you did was sculpt and write and translate?’ I ask. ‘It has been three decades. How is your translation of Lal Ded coming along?’ I ask playfully.

During this time, I’ve read through his work, and I’ve asked him many questions. Dealing with the symptoms of an ageing mind, he has answered some with words, some with a smile, and some with silence.

Once, in response to my question, he described his interpretation based on how he imagined Lal Ded would have written her vaakhs in English, if she did.

His translation is like the metaphor of the onion Lal Ded herself refers to in her vaakhs; it has layers upon layers that are waiting to be scratched and unpeeled. But to that exercise is attached an element of struggle. It’s not easy to get to the core of this creation … the translation and, in the light of philosophical and spiritual discourse, existence.

This creation is layered by the dust of the passage of time, the creative spirit of my father’s mind, and the mysticism and esoteric nature unique to Lal’s Ded’s four-lined, succinct verses.

‘It has taken you over thirty years, and your translation still lies incomplete,’ I continue to probe him.

Pa smiles.

‘Lal Ded’s philosophy is eternal. It can take a lifetime, and more, to understand it,’ he says. ‘My translation will always remain unfinished…’

***

The tear

the sigh

the lamentation

are mine.

Consciousness chained by shadows.

This feast a bubble.

So forgetful of where and what you are!

***

You are the garden.

Uproot the weeds

and then

take in the daffodils.

Judgement awaits when you go.

The tax collector

walks behind you.

Death!

***

Where did I come from?

Which way will I go?

I am at the crossroads.

Come,

my path

my guide.

False breath is the liar.

***

The whole of me went to him.

I heard the chime of the bell.

I was stillness.

I knew the void

I knew the light.

No arrows sting me.

When I surrender

the mud clears the mirror.

When I surrender

the mud is dew on lotus.

***

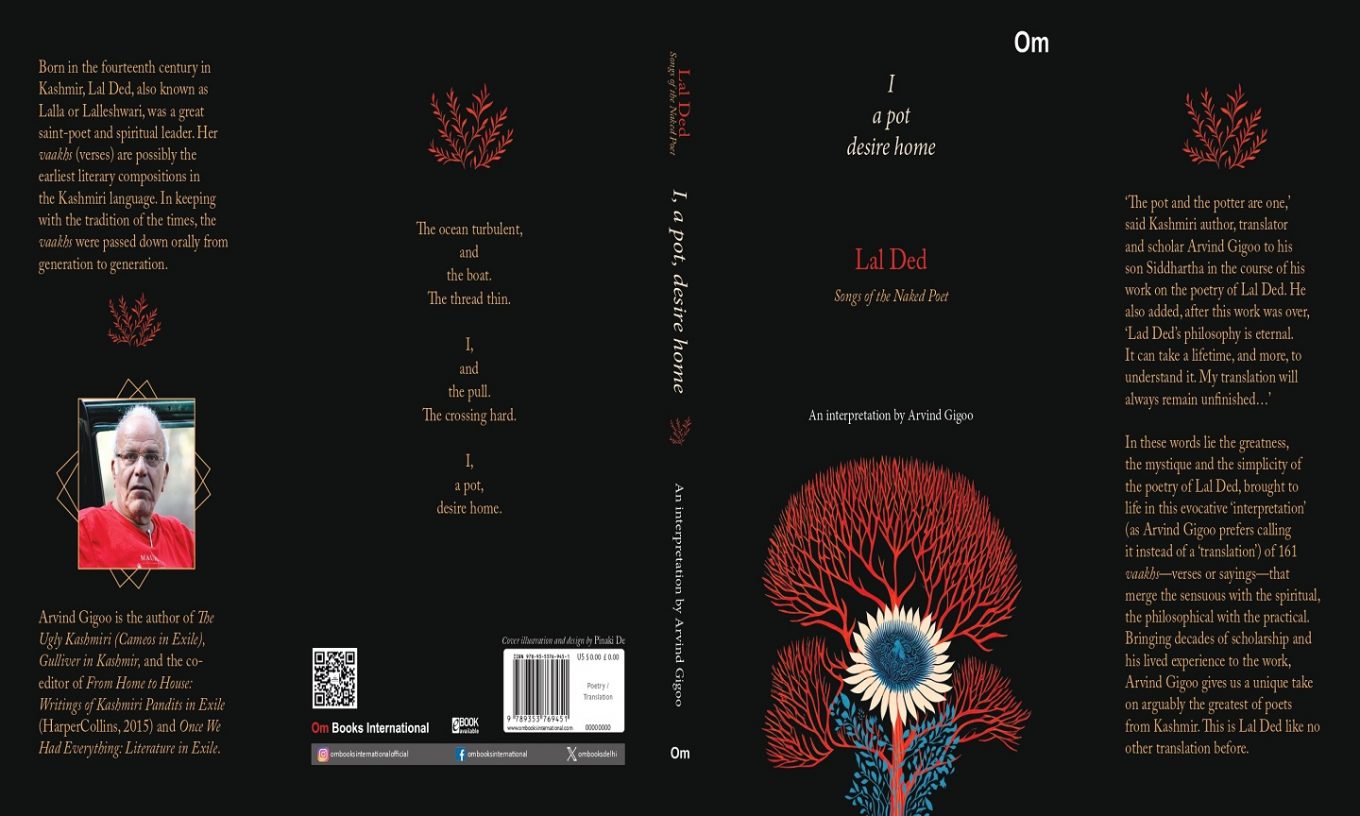

TRANSLATOR’S BIO:

Arvind Gigoo is the author of The Ugly Kashmiri (Cameos in Exile), Gulliver in Kashmir, and the coeditor of From Home to House: Writings of Kashmiri Pandits in Exile (HarperCollins, 2015) and Once We Had Everything: Literature in Exile.