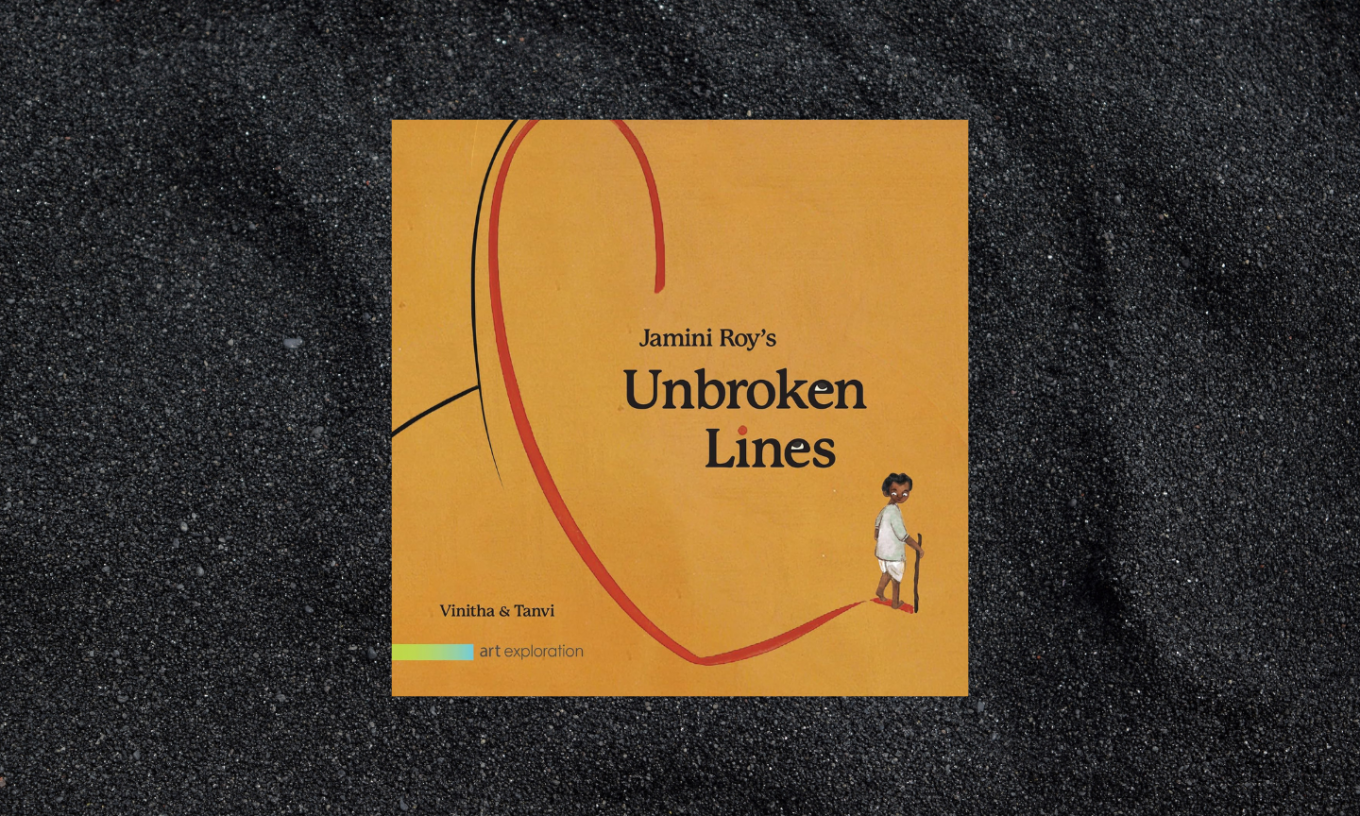

Jamini Roy’s Unbroken Lines, by Vinitha and Tanvi, is the sixth in ‘The Art Exploration Series’ published by Art1st and Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, with Akar Prakar as the research partner. The first five were on Ambadas, S.H. Raza, Somnath Hore, Abanindranath Tagore and Meera Mukherjee. Each explores a representative aspect of the artist’s work (Raza’s ‘Bindu’, Hore’s ‘Wounds’); the purpose being not to give a chronological sequence of life and works, but the graph of a distinct artistic preoccupation – through an engaging narrative.

The graphic narrative

When he looked, the ant was up.

He had been watching this ant, this tiny fellow,

in a giant land of leaves and dusty pebbles.

***

There were other ants, but Jamini liked this one. It had

paused to examine the alpona his mother had drawn.

Thus begins the graphic narrative of Jamini Roy’s Unbroken Lines; the two bits of text quoted above diagonally spread across two pages, the top right of the second opening a huge round flap of alpona, folded in four. Inside the semi-circle of the flap, we are told: Every creature loves the alpona, Jamini thought. And then in the next page, we find Jamini wonder: How does it know where to go?

This Jamini is a little boy, all of seven, clad in half-dhoti and photua, with big bulging eyes and a head full of curly hair. We see him in his village, Beliatore, in the Bankura district of undivided Bengal, living with his parents, grandparents and elder sister. The narrative of his deciding to become an artist at a tender age is told through his fascination with the little ant, which despite being tiny evidently had a mind of its own.

The first part ends where it began, the circle coming round – with Jamini and the ant; the boy drawing a gigantic alpona-portrait of the ant, with the tiny creature posing before him!

He remembered the ant. A storm couldn’t get an ant

lost. Yes, thought Jamini. He didn’t need anyone to tell

him what to do. Jamini knew.

As with any other children’s book (regardless of the subject), it is the flaps that are the most delectable part of this one too. Like the alpona at the beginning, five more such ingenious flaps – all very different from each other – surprise the intended young reader as she advances in the narrative: a flap-within-a flap of a slate that Jamini’s father gives him “to count and write”, on which his mother says he can draw too; a three-panel, two-page spread of Jamini messing his hands with mud and water, with an extension folded back with the second page; a scene of the family gathered together on a bed in the evening, seamlessly cutting out of the wall of the room; a three-page construction where the third opens out and lands as a base once the book is held vertically, showing Jamini’s many experiments with organic colour and animal form; and a drop-down of his sister calling him from the edge of a crate, where he is lost in creating a little animal world.

The lushness and beauty of rural Bengal; the rhythm of quotidian life in a simple household; and a curious and sensitive child’s endless wonder about the sentient beings that make up the natural world around him – these are powerfully conveyed through the design of the flaps.

At the end of the narrative, the reader is projected into the little boy’s future:

Later, much later, even when Jamini had made a mark for himself, he chose to

retrace his steps Simplifying and further simplifying, his lines of innocence were ones

his heart dictated. Like master craftsmen of ancient India, his studio was once

again a place where students and assistants learnt and worked. Jamini directed his

own journey. Like the ant, he watched, he stopped, he paused; and when he was

ready, he made his own path.

Jamini Roy’s art

The graphic narrative of the first part of the book gives way to two more sections that are invitations to ponder on Jamini Roy’s art – ‘Think Like An Artist’ and ‘Create Like An Artist’. Through a judicious selection of some of his most well-known artworks, the reader is nudged into thinking about certain aspects of his artistic preoccupation with animals (Krishna and Balaram), the Santhal tribe (Santhal Girl, Standing), divinity (Last Supper), and his use of lines.

But perhaps the most interesting part of the book is the do-it-yourself exercises in the final ‘Create Like An Artist’ section – which encourages readers to engage with Roy’s art by emulating some of the processes involved: outlining faces (Mother and Child), exaggerating features, making toys (Black Horse), creating organic colors (with flowers and leaves) and testing them out.

If the first part delights the general young reader, the two later sections are bound to attract those children more who are themselves inclined towards art. And their interactional engagement with the book may later lead them to understand the bio note of the artist at the very end:

One of the most significant modernists of the 20th century in the world of Indian fine arts, Jamini Roy is known as a rebel artist who rejected his western training and chose to develop his voice as an artist by finding his own translation of folk art. His work is a meditation of fluid, unbroken lines.

A mother-and daughter

This reviewer has had a three-fold interest in this Series (which expressly “advocates the importance of visual art education”): her interest in art books and her belief that it should be made more available and accessible to all; her more specific interest in children’s illustrated books on art and history, as the best way of introducing them to those subjects; and, probably, most importantly, in introducing her daughter – who can spend the whole day drawing – to the best of Indian art.

The child was in Junior school when they read Somenath Hore’s Wounds together; and she is now in middle-school, when they did the same with Jamini’s Roy’s Unbroken Lines. She is probably already past the age this book is intended for, but not past the joy and benefit of doing the “exercises” it recommends to its young readers in the second part.

The sheer visual delight the book affords is for all ages. It can be picked up and cherished for that alone.