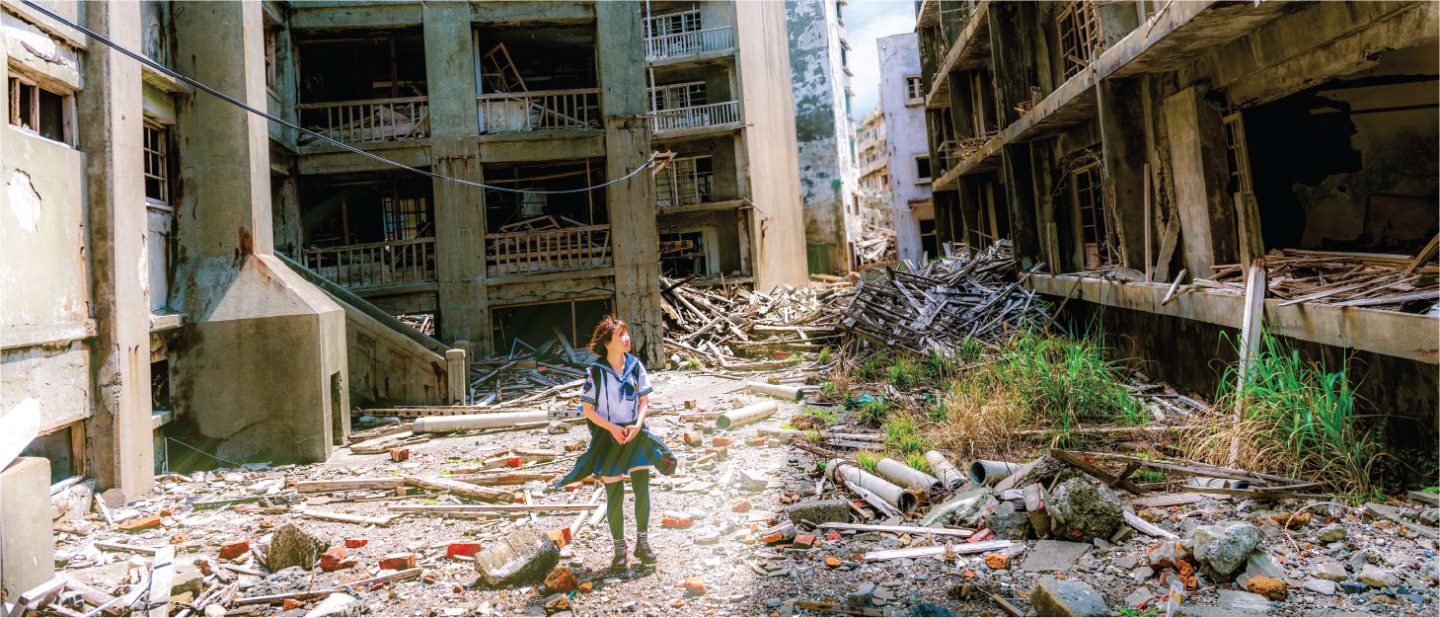

The war was over, but for how long we didn’t know. The streets were filled with debris and fires. As we walked among the bombed out buildings, now and then masonry and shards of glass dropped from upper stories. Of course, there were bodies everywhere; I whispered to the children that these were merely people sleeping and not to worry. It was all a dream, I assured them, and soon we would reach home and awaken. The trolleys and busses were bombed out, and there were no other vehicles, save for a deserted tumbrel drawn by a horse dead on its knees. We walked past a string quartet, sitting in the middle of a square playing frantically but without instruments. My youngest daughter found that so amusing; I had not seen her smile like that in weeks. “Gorecki’s Symphony No. 3”, said my husband bitterly. And all the while we kept pushing the wheelbarrow filled with everything to our name.

Eventually, we reached the hotel. The clerks had gone, but one of the old bellboys stirred as we made our way through the lobby and went up to our rooms. As I stood on the balcony, the most gorgeous Mediterranean day suddenly unfurled. Down in the street, a young woman and her family were walking several rickety little dogs. They were small enough to put in your hat; I’d never seen such a breed.

I had a new, white tennis ball and was going to throw it to the dogs, but then it occurred to me I should ask the woman if she would like to throw it herself. I shouted down. She looked up with a terrified expression, but after a moment she smiled and reached out her arms. “Yes, yes,” she said.

I let the ball drop.

A year earlier she caught it and threw it toward the bay below the town. The dogs gave chase but the ball rolled into the water and they stopped. The bay was full of activity: boats, balls, swimmers, people on boards and colorful rafts with cabanas and kites. Reminiscent of The Bay of Naples, by Vernet. But no, this was another painting, done from memory in the dead of night.

When we reached the shore, the water was absolutely flat. We went out on surfboards, my son and I, to watch the gray whales sounding. Everyone was relaxed, smiles as far as you could see. But what if we’re under one of those whales when it comes up, I wondered. My son shook his head, as if to say, ‘why do you always spoil things with your pessimism?’

The wind picked up, the water turned white with panic and someone, an authority I knew, drew up a diagram on a blackboard outlining the chemical properties of cataclysm. We were advised to go back to shore immediately. Wait, I said to my son, suddenly remembering where his father had hidden a piece of music he’d composed years ago.

Later, as we walked back to the hotel, I reminded him to keep smiling as we looked out at the museum patrons, standing quietly in a clump, examining the brush strokes, discussing how the atmospheric effects combined with a sense of harmony.

M

Museum Canvass Rarely Seen